“NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star” proposes that an art exhibit can function as a time capsule. The current exhibit at the New Museum in New York City takes a cross section of the art and culture produced in 1993 and displays it in the museum in no particular order and with no particular agenda. There are works from artists already famous in 1993 — like Kiki Smith — and artists who would soon become famous, like Mathew Barney. But there are also plenty of works from artists you’ve never heard of. Some of the work in the exhibit was originally shown in big galleries and museums. But some of it was never officially shown at all, or was only available in little-known galleries and private artist studios. The point of “NYC 1993” is to give a sense of what might have been encountered across the cultural landscape of New York City 20 years ago.

- “NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star”

Through May 26, 2013. The New Exhibitions Museum, New York.

Promotional material for the exhibit argues that, “The social and economic landscape of the early ’90s was a cultural turning point both nationally and globally,” and that 1993 was a “pivotal moment in the New York art world.” But this is mere nervousness on the part of the curators, who don’t want to be accused of creating a show that is utterly arbitrary. The perfect thing about 1993 is that it has no special significance. In the grand scope of history, 1993 means nothing.

The non-essential nature of the year 1993 is what makes it the proper subject for a time capsule. Time capsules are meant to give an overall picture of one period of time so that another period of time in the future can know what life was like back then. And if you want to give an overall picture, you want to stay away from extraordinary events or unusually significant points in history. You want to focus on the mundane. That is how Dr. Thornwell Jacobs saw it anyway. And Dr. Jacobs has been credited as being the “father of the modern time capsule.” This goes back to the 1930s. Dr. Jacobs was annoyed that ancient civilizations had left the modern world so little to go on. A few scraps from a tomb here, a broken down ruin there. Nothing comprehensive. Since the past could not be fixed, Dr. Jacobs decided to fix the future.

He began work on what he called the Oglethorpe Atlanta Crypt of Civilization. Dr. Jacobs was a professor at Oglethorpe University in Georgia. His idea was to collect objects, documents, cultural artifacts, nick nacks, scientific implements, pop culture — everything really — and store it in a vault not to be opened until 8113 AD. Whoever opened the time capsule in the 82nd century would get a good sense of what people had been up to in the 1930s. There are some “important” things preserved in Dr. Jacobs’ time capsule. There are copies of historically significant speeches. There are newsreels, scientific formulas, and industrial implements. But the Inventory of the Crypt of Civilization also contains much that is less vital. Inside the Crypt, there is one Toastolator (electric). There is one package of Butterick dress patterns. There is one Masonic deposit (5 badges, 1 metal plaque in case, sealed). There is one Mazda lamp exhibit (component parts). There is one sample of soap (figure of a bull). There is one glass jar containing 1 hair bow, 1 gem razor, 1 package blades, 1 shaving brush, 2 powder puffs, 2 compacts, 3 samples powder, 1 eyebrow brush, 3 lipsticks, 1 hair remover, 1 toothbrush, 1 rouge, 1 nail brush, 1 ivory stick, 1 pair manicure scissors, 1 eyelash curler, 5 hair curlers, 1 package dental floss, 1 pair tweezers, 1 package Mallene, 1 package corn pads eye cup, 1 set artificial fingernails, 1 set artificial eyelashes, 1 package playing cards, 1 set Bridge tally cards. There is one lady’s breast form. There is one package fly swatter and coat hanger. And so on.

It was essential to Dr. Jacobs’ concept of the time capsule that an everyday object like a toothbrush might turn out to be just as fascinating, just as informative to future generations as any other object. For that reason, he tried to put in everything he could think of. The Oglethorpe Atlanta Crypt of Civilization is jam packed with junk.

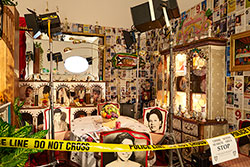

“Garage Renovation New York (Cherry Makita),” Jason Rhoades (1993).

The New Museum’s exhibit, like any good time capsule, is also packed with junk. In proper ‘90s style, some of the works included in the show are even comprised of junk. A work by Jason Rhoades, “Garage Renovation New York (Cherry Makita),” is Rhoades’ recreation of a typical cluttered garage that might be found in any neighborhood of America, circa 1993. It is, itself, something of a time capsule. The same thing could be said of Nayland Blake’s “Equipment for a Shameful Epic,” which consists of a clothing rack full of costume clothing, masks, and accessories for what must have been a salacious romp. You could call it a time capsule of the dark fantasies of 1993. There is also David Hammons’ “In the Hood,” which is nothing but the hood of a typical sweatshirt worn in 1993.

“In the Hood,” David Hammons (1993)

The challenge for any time capsule is to make the junk speak. That is what Dr. Thornwell Jacobs wanted to do with his Crypt of Civilization. He couldn’t put everything in his Crypt, just as the New Museum could not show every work of art produced in 1993. You have to pick the right stuff, even as you must preserve the feeling of randomness that makes a time capsule into an authentic “snapshot” of the time. Reading through the inventory of Dr. Jacobs’ Crypt one does begin to form a picture, however enigmatic it must necessarily be, of a moment in civilization that is held together by Artie Shaw records, motion pictures, dentures, electrical cords, strips of rayon, Donald Duck, and quite a bit of plastic. It is the picture of an emerging consumer society that believes in itself, in the future, and in its role as culmination and apotheosis of all that has come before.

A picture also emerges while walking through the rooms of the New Museum exhibit. What this picture shows most clearly, in the random collection of works of art produced in the year 1993, is a culture that has no idea what it is about. This point has, of course, been made over and over again. We live in a fragmented world in which we piece together our fragmented identities. And all of this fragmentation was happening long before 1993, decades before. By the 1970s, the idea that art had to be about anything in particular had long given way. The critic and philosopher Arthur Danto wrote an essay in the early 90s entitled “Art After the End of Art.” He argued:

The seventies are a fascinating period whose art history is as yet uncharted, but it is certainly, as I see it, the first full decade of post-historical art. It was marked by the fact that there was no single movement, like Abstract Expressionism in the fifties or Pop in the sixties — or, delusionally, Neo-Expressionism in the eighties.

It’s clear now that the 90s shared much with the 70s. The art of “Experimental Jet Set. Trash, and No Star” is all post-historical art. According to Danto, post-historical art cannot and should not be dismissed. You could see the 70s as a decade in which “nothing happened.” But it was actually, Danto argues, a decade in which “everything happened.” Artists were freed up from thinking that art must pursue this or that agenda. A “golden age” of pluralism emerged in which artists, “pursued what they were interested in whether it was really art or not.”

“Untitled (Couple),” Felix Gonzalez-Torres (1993).

The artists of 1993 were certainly pursuing what they were interested in whether it was really art or not. In the New Museum show, there is a string of light bulbs hanging from an extension cord by Felix Gonzalez-Torres. There is a work of art by Rudolf Stingel that is simply an orange wall-to-wall carpet taking up one floor of the museum. There is a video loop by artist Lutz Bacher showing a clip from William Kennedy Smith’s rape trial where he mentions his penis and then winces. There is a reproduction of the lithograph posters made by Marlene McCarty and Donald Moffett that honor Allen R. Schindler, a gay member of the Navy who was beaten to death by a fellow sailor angry about his homosexuality. These are recognizable as works of art only because they say they are and because they are presented as such. Shift the context, and they could easily be something else: home decoration, political activism, consumer product.

“In Honor of Allen R. Schindler,” Marlene McCarty (1993).

Arthur Danto’s central point is that there is freedom and celebration in the wide-open field that is post-historical art. The artists who truly embrace this fact are the artists who thrive in such a milieu. These artists, according to Danto, “have no easily identified predecessors, are in fact those who do everything themselves, and in whose oeuvre there is in consequence a certain magnificent openness, whatever one thinks of the component works.” There are works in the New Museum show that seem to achieve that “certain magnificent openness.” Take the photographs of Wolfgang Tillmans, for instance. His portraits of “Steph and Christopher” and of “Bernadette and Thuy” skillfully capture something genuine about persons living in 1993. The portraits don’t tell us what to think about the people of 1993 or even about 1993 itself. Instead, they show us what personhood was like in 1993, they give the conditions of that personhood.

From left to right: “Gillian & Christopher,” “Gillian & Christopher on Floor,” “Bernadette & Thuy,” “Moby lying,” and “Steph &Christopher.” All prints by Wolfgang Tillmans (1993).

But even in art like Tillmans’, art that displays a “certain magnificent openness”, there is uneasiness too. What Arthur Danto misses in his celebration of post-historical art in all its possibility is the anxiety. There is a great anxiety lingering over all the works included in the New Museum show. Some of this anxiety has a direct and obvious cause. AIDS, for instance, was a terrifying presence to the artists of New York City, 1993. And the anxiety of AIDS is felt directly in the work, like in an hour-long video by Gregg Bordowitz (Fast Trip, Long Drop), which is a film about the reality of dying of AIDS. Or sometimes the reference is more indirect, like in the photographs of Andres Serrano’s “Morgue Series,” one of which portrays the hands of a person who has recently died of AIDS.

But even the specific anxiety about AIDS or about politics or social issues of the ‘90s isn’t the greater anxiety I am referring to. There is an anxiety about art and what the artist is doing that hovers over all the work, and that is heightened in the aggregate. Kierkegaard would have understood this anxiety as a “dizziness of freedom.” The dizziness comes when a person knows that he or she must make a choice, but is unsure about the basis for that choice. I know my art must be about something, the artists of 1993 were thinking — but what? I know I must choose one medium over another — but why? It is also a dizziness born of fear. A choice, once it has been made, must be followed through on. Something is at stake. The choice could be wrong. Anxiety intensifies the longer one remains in the position of choice, the longer one stands in the dizziness of freedom. Anxiety that cannot be resolved, that does not lead eventually to a choice will, according to Kierkegaard, make you sick. This isn’t just a physical sickness; it is a soul sickness.

The artists of 1993 were facing this kind of anxiety; they were confronting a sickness of soul. The responses are as diverse as the number of artists. That is the wonder of post-historical art, the wonder that Danto celebrates, the wonder that art can be so many things, infinitely many things. But the story of art in the post-historical age is not complete unless the anxiety is accounted for as well. The anxiety makes the freedom potentially dangerous. The artists of 1993 knew it was dangerous. They were struggling with an anxiety that was not always pleasant or productive. There is great freedom being explored in this time capsule at the New Museum of Art. That freedom is doggedly accompanied by a no-less-great fear. This is as Kierkegaard always set it would be: “There is nothing with which every man is so afraid as getting to know how enormously much he is capable of doing and becoming.” • 26 February 2013