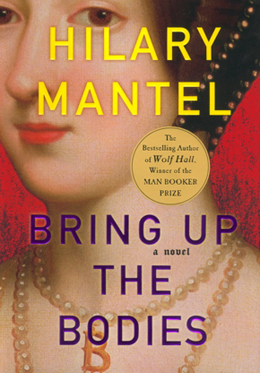

The critic James Woods, disdainful of the cold and calculating set piece of historical fiction, finds something else in Hilary Mantel’s recent Bring up the Bodies, the breathless follow up to her Man Booker Prize-winning Wolf Hall: the ring of the contemporary. “One of the reasons for this literary success,” Woods writes in the New Yorker, “is that Mantel seems to have written a very good modern novel, then changed all her fictional names to English historical figures of the fifteen-twenties and thirties.”

But is it quite so easy? And is there not a cost to portraying figures from the past as if they were in effect mirrors of our own reality? In his new collection of essays, Waiting for the Barbarians, the classicist and critic Daniel Mendelsohn says the danger is that we risk losing the particular reality of the period and place that’s being interpreted — and worse, we may be getting it wrong. Contemporary interpretations of the ancient poet Sappho, whose work only survives in fragments, he says, are rife with this kind of manipulation. “Many classics scholars have been wondering whether Sappho’s poems meant something wholly different to her and her original audience from what their partial remains mean to us,” he writes, in the essay, “In Search of Sappho.”

Which reality, then, ought historical fiction address: ours, with all its textures and biases, or the reality of say, England in 1536 or Ancient Greece? I’ve found myself grappling with this question in the writing of a novel, The Book of Masters (forthcoming in 2013 on the Head and the Hand Press), about the tragic 1821 death of American genre painter John Lewis Krimmel. I started thinking about transforming Krimmel’s story into a novel when I was 32, the same age Krimmel was when he died. Indeed, as a long-time documenter of the life of Philadelphia, where Krimmel lived, sketching and painting street scenes and inside taverns and market stalls, I saw myself mirrored in him. The novel would be a contemporary one that happened to be set in the early 19th century. I had no intention to create a work, as Woods puts it, “entangled in the simulation of historical authenticity.”

I felt all the more justified in thinking this way because the historical characters I would portray were themselves, in the forging of a new American reality, rather wantonly pillaging the fragments of Western civilization, from imperial England to Ancient Greece. Indeed, the antagonist of The Book of Masters is Charles Willson Peale, who named his own children after the great masters—among them Raphaelle, Rembrandt, Rubens, Titian, even Sappho — and who sought to train them in the arts by having them learn from copies of the great paintings.

Semblance, copying, stealing, borrowing: these would become the very contemporary underpinnings of the novel. One of the rather notorious characters to cross paths with the real Krimmel was a Russian attaché named Pavel Petrovich Svinin, a buffoon who stole Krimmel’s watercolors and published them in a book on North America as his own (despite substantial evidence of this, the Metropolitan Museum of Art still attributes the works to Svinin). Svinin returned to Russia, falsified his membership in the Russian Academy of Art, and set himself up as a minor self-righteous government official. This real Svinin, infamous as he was, inspired Nikolai Gogol’s 1836 satirical character, Khlestakov, the Government Inspector. My Svinin, in a fun literary game, would have to embody the most delicious parts of Khlestakov.

Mendelsohn, whose writing I very often admire, would almost certainly assign this approach to an impulse of “our present postmodern imagination, with its obsession with fragmentation, allusiveness, quotation, and reconfiguration of elements of the past,” and label it false or dishonest.

But The Book of Masters emerges from my own rather genuine experience studying Philadelphia’s history (I am a co-producer of a multi-part history documentary on the city); I was strongly motivated by a desire to understand the state of America on the cusp of industrialization, about to experience exploitative capital (Krimmel’s death is, in one interpretation, an industrial accident). Did things have to go the way they did? Was Krimmel’s pastoral America doomed?

These kinds of questions force the writer of historic fiction to attempt to understand, as honestly and thoroughly as possible, the circumstance of the past being portrayed, and to remember, as Woods says of Mantel, “that at every point things could have been different.”

This sensibility goes along with Mantel’s hot and tight prose style (which seems to match a world that was, in fact, shorter and thirstier and angrier than the world of today) to animate Bring up the Bodies. Here is Thomas Cromwell, senior aide to King Henry VIII, having retreated to his quarters to work.

These are sounds of Austin Friars, in the autumn of 1535: the singing children rehearsing a motet, breaking off, beginning again. The voices of these children, small boys, calling out to each other from staircases, and nearer at hand the scrabbling of dogs’ paws on the boards. The chink of gold pieces into a chest. The susurration, tapestry-muffled, of polyglot conversation. The whisper of ink across paper. Beyond the walls the noises of the city: the milling of the crowds at his gate, distant cries from the river. His inner monologue, running on, soft-voiced: it is in public rooms that he thinks of the cardinal, his footsteps echoing in lofty vaulted chambers. It is in private chambers he thinks of his wife Elizabeth. She is a blur now in his mind, a whisk of skirts around a corner.

Woods says, “it could almost be thought today.” But more than anything, Mantel’s access to Cromwell’s inner monologue makes the novel feel modern. Still, we have to ask, does this sort of imagining of 16th century people get them right? Does it anyway matter? Woods says no, not really. Mantel’s novel reads true because it feels alive and resonant with the 21st century reader.

The Norwegian novelist Karl O. Knausgaard, who rose into American literary consciousness only a year ago with Don Bartlett’s translation of his 2009 book My Struggle, presents another possible path to truth in historical fiction. In the first page of the earlier A Time for Everything, translated by James Anderson, Knausgaard presents a fictional 16th century Italian writer and theologian, Antinous, about whom little is known. (A real life Antinous was a lover of Hadrian — little is otherwise is known about his life outside what Margerite Yourcenar presented in her exquisite historical fiction Memoirs of Hadrian. More recently he has been repurposed as “the gay god.”) “But if one is to attempt to understand Antinous, it isn’t to the inner man one must turn,” writes Knausgaard. “For even if one succeeded in charting his inner landscape as it actually was, right down to the smallest fissure and groove in the massif of his character… Even if the events and relationships of his life were to correspond exactly with a life in our own time, one that we could understand and recognize, we would still come no closer to him. Antinous was, first and foremost, of his time, and to understand who he was, that is what must be mapped.”

This frustration with historic fiction, a meta theme of The Book of Masters, is expressed in that book by Joseph Bonaparte, the brother of Napoleon, after meeting Charles Willson Peale. You can’t just manufacture a civilization based on poorly understood fragments of another time and place, he says. “It surely can’t be possible that all one must do is name his children for Titian, Rafaello, Rubens, or Rembrandt? Can this really be?”

Indeed, says Knausgaard, we are wrong to imagine that those of the past are anything like us, for “our world is only one of many possible worlds.” If that is so, are we doomed to mere conjecture? The Norwegian’s answer in the mesmerizing A Time for Everything, a book about the experience of angels, is to try to imagine the circumstances in which angels were visceral and real in the lives of human beings. He does so by retelling the biblical stories of Cain and Abel, Noah and his ark, and Ezekiel not in the stilted language of ancient text but in unpretentious prose of today. In this disarming guise, the ancient lands are filled with dark forest and snow banks and fjords as if they were contemporary Norway and the characters live in houses with bedrooms and kitchens and wear sneakers. What matters — what is true — in the case of Cain and Abel is the nature of the relationship between the brothers (which Knausgaard deconstructs with psychological precision) and their tragic interrogation of the angels. Can we really understand it?

But we don’t care if we can. Cain and Abel are indescribably like us and they aren’t like us at all — they speak to us of things we know not in a language we find so easy to understand. • 21 March 2013