Now, here’s an interesting walking cane.

It was made in Holland sometime in the 19th century. It has an ebony shaft and is 35 inches long. The top features an ivory finial depicting a four-inch-high man with muttonchops. The man is squatting, and evidently taking a dump. Perhaps it’s best if I now just quote the auction catalog: “He holds in his hands between his legs an eel-like animal that stretches ahead to become his sexual organ when the button on the back is depressed.” This cane sold a couple of years ago for $8,000.

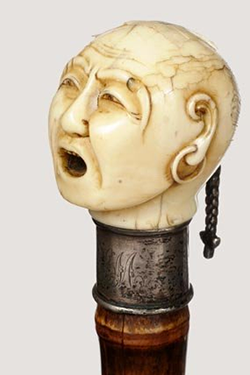

Victorians often get tarred as a stodgy and uptight, but not by those who’ve seen some of the walking sticks they promenaded around with. Naked women carved in ivory were a popular motif, as were couples intertwined to look like complicated knots. Some top knobs hinged opened to reveal elaborate fornication scenarios; one might reasonably conclude from these that the 19th century was wholly unfamiliar with the missionary position. Oh, and here’s another: a lusty jackass is having its way a naked woman. Still, canes weren’t all about sex. Another cane is topped with a carved ivory bust of an Asian man; you pulled his ponytail and water (or some caustic you’ve put into the reservoir in the shaft) spews out of his mouth. It can projectile spit up to eight feet.

We may think of canes today as that dull, clattery flotsam that washes up in the umbrella stands of our infirm relatives. They’re simple, archaic tools that help the elderly get around without pitching over. (“A walking stick is a device used by many people to facilitate balancing while walking.” Remind me: How did we get through the day before Wikipedia?) Wooden canes seem to be falling out of fashion; more common these days are canes of sturdy but lightweight aluminum, sometimes kitted out with three tips for stability, like the splayed trident of obscure marine royalty.

A century and a half ago, walking sticks and canes weren’t just associated with the aged, but with young dandies and others of dapper inclination. These were essentially vestigial artifacts of the 16th and 17th century, when nobility carried canes encrusted with jewels, which were themselves distant ancestors of royal scepters conferring power. For a time, ornate canes were made by Faberge in Russia and by Tiffany in the United States. A craze for canes made of allspice wood nearly pushed these West Indian trees into extinction. The Malacca cane, made from a prized type of rattan, was hugely in demand around 1900. As one writer put it at the time, he knew of those “who make a cult of Malacca canes, just as some dog fanciers are devotees of the Airedale terrier.”

But as status objects are wont to do, these markers of status migrated over time further down into the middle classes, who wanted to affect a regal air. In 1847, Paris had 165 workshops employing nearly a thousand people making walking sticks and whips, presumably not all for nobles. The latter half of the 19th century was the golden era for flamboyant canes. Even as late as 1918, Robert Cortes Holliday wrote of their popularity, noting that, “a man cannot do manual labour carrying a cane,” and therefore it is “a symbol of a superior caste.” Holliday added that “canes are indispensable to the simple vanity of the Bohemian” and observed that “all artists carry them; and the poorer the artist the more attached is he to his cane.”

Yet even Bohemians needed tools. So canes were developed to have practical uses while cleverly hiding their utility. Last Saturday, the Kimball H. Sterling Auction Gallery in Tennessee held a sale of more than two hundred vintage canes, including a great number of what collectors call “system canes.” One was designed for midwives and had a baby scale hidden within it; others concealed a picnic utensil set, opera glasses, an ear trumpet, a perfume bottle, a detachable baby rattle, a blow gun, a winemaker’s thermometer, a folding fan, a telescope, a flask with cork top, a pocket watch, a sewing kit, a compact and mirror, a full-length saw blade, a microscope, a pennywhistle, a set of watercolors and paintbrush, a whistle for hailing a cab, and gauges for measuring the height of a horse.

The Victorian walking stick was the Swiss Army Knife of the pre-automotive era: something useful, easily carried, able to provoke small wonderment when shown off, and useful as weaponry in certain circumstances.

Indeed, canes were commonly employed as simple offensive or defensive weapons — just by wielding it like a truncheon, a walker could keep snarling dogs or timid bandits at bay. The most famous incident of violence involving a cane was no doubt the 1856 attack on Senator Charles Sumner on the floor of the United States Senate by Preston Brooks, a 37-year-old representative who pummeled the senator unconscious while simultaneously setting the gold standard for congressional incivility.

When even more firepower was needed, canes could deliver. A great many canes hid sword blades or dirks, or had shafts that were actually rifle barrels that could be hoisted and fired. A writer in 1892 described taking a country walk with a friend, who at one point suddenly raised his cane to his shoulder and popped a partridge, which fell “as dead as a hammer.” The shooter said the cane allowed him to poach while feigning innocence, and avoid alarming people by strolling about with a gun.

Walking advocates often point out that walking is the People’s Sport — it’s democratic because you don’t need any special equipment and it can be practiced by almost anyone. But that’s actually something of a problem. Because if walking required special equipment or skills or incurred expense, it would be a multi-billion dollar industry. And if that were the case, business owners and politicians alike would fall over themselves to enhance and protect spaces where we walk. Instead, we end up with sidewalk-free arterials, eight-lane crosswalks, and parched, treeless lanes. (Note that it doesn’t require much in the way of special equipment to put your feet and palms on the floor and your butt in the air, yet yoga is now a $5.7 billion dollar industry; it sometimes appears that quarter of the commercial real estate near my house now consists of empty studios with bare floors, and shops selling the sort of stretched-out, loose clothing people once regularly donated to Goodwill).

But walking hasn’t spawned it’s own industry… walking is too easy, it’s too accessible, it’s too, well, pedestrian. Some years ago a magazine called Walking was published, but it went out of business. And so walking gets overlooked.

Canes mark a time when we once walked everywhere, and it was central to our lives. Walking was cruising before cars took over. And you didn’t just go schlumping around in your velour sweats. You put on a walking outfit and you walked with purpose and style. (Walking historian Geoff Nicholson writes about the Italian verb cammellare, which is to walk like camel, “a style adopted by disaffected youths who slouch along, head down, creating a camel-like hump on their backs.”) You also learned posture and proper walking technique. Here’s advice from a 1903 guide: “Stand at attention, head up, shoulders thrown well back, chest expanded, hands at side… as if you were attempting to walk along a tight rope.” Call it the High Rope Position.

One might argue that walking sticks are, in fact, returning. I’ve seen more and more of those telescoping aluminum poles deployed along backcountry trails. They’re often used in pairs, and favored by people clad in sherbet colors and fitted with an intricate IV system that involves hydrating tubes connected to humps on their backs. They clang down trails like arthropods, using their aluminum mandibles to clear a path before them and ensure I step to the edge and let them by. I’ve noticed an inverse correlation between the use of paired aluminum walking sticks and eye contact — they’re often like car drivers who don’t like to make eye contact with pedestrians.

Last week I stopped by an outdoor store in British Columbia to have a closer look at modern walking sticks. They were sleek and ergonomic, and both lightweight and durable, although utterly lacking in ornamentation or sexual innuendo. None came equipped additional tools for artist or midwife, although one pair came with shock absorbers built into their tips. When I asked the clerk why he would recommend anyone use these, he told me, “It’s basically like having four wheel drive rather than two.”

Walking has within a century evolved from being an art and a means to express oneself to a rather joyless means of transport for the poor. The intricate walking sticks that surface at auctions and antique shops are poignant artifacts of an era. They were the era’s 22-inch rims with spinners. Canes conveyed. Like rain drops fossilized in mud that capture a storm that passed by many millennia ago, they can only suggest a world that’s long since faded in our rear view mirrors. • 17 April 2013