“Nothing an artist could do was thought of really offensive anymore,” critic Robert Hughes declared of art in the 1970s, “because there was always the chance it might be converted into capital.” He added, “everywhere there was instant art for instant people.” Hughes’ critiques were part of his eight-part television series on modern art, The Shock of the New, which premiered in America in January of 1981. Originally produced for the BBC, the series aired on public television stations across the country, offering viewers a history lesson in the rise and fall of modern art. Tracking the beginning of modernism in 19th-century Paris, each episode offered Hughes’ unwavering critique of where modernism went wrong (architecture most often) and, more intriguingly, how it abandoned its avant-garde origins as it became a cultural style and investment commodity in the 1970s.

- “Cindy Sherman.” Through June 11. Museum of Modern Art, New York. July 14 through October 7. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. November 10 through February 17, 2013. Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. March 17, 2013 through June 9. Dallas Museum of Art.

In one scene, Hughes walks the streets of SoHo in New York City, commenting on how the neighborhood he moved to in 1970 had become an artistic boutique, wreathed in a chic aesthetic that was a far cry from the bohemia of Montmartre. Then, a montage of street shots presents the young denizens of SoHo on a warm summer day. Shirtless men in tight shorts; women in T-shirts and jeans; and other, more elegantly dressed couples meander in front of revitalized tenement facades. These images mix with shots of gallery storefronts. In a contrasting moment, a hunched crone goes looking through a trash can, all of it punctuated with the soundtrack to Bryan Ferry’s 1974 classic “The ‘In’ Crowd.” The visual and aural cues are clear: The avant-garde is dead. Modernism is dead. Both had been replaced by stylish hipsters and Roxy music.

In another shot we see Hughes himself wandering amid these folks. He’s wearing a simple white dress shirt and jeans. His sturdy body and slightly stiff cowboy gait all convey a certain rakish demeanor coupled with an outsider’s distain. Throughout the series, Hughes plays the part of both critic and adventurer, a role underscored by his Australian accent. He’s a tough but erudite skeptic who longs for a more robust modernism. But however predictive and accurate Hughes critique of the demise of modern art under the “propaganda of art as investment” may have been (and he was quite accurate), his concern about contemporary art was also a concern about the loss of the male artist as the icon not only of modern art, but of the radical, and subversive avant-garde. For the most part, Hughes’s survey of modern art celebrated great men, who, one is meant to assume, cared little for boutiques or style or fashion.

Near the very end of the last episode, in an interview with William Rubin, then chief curator at the Museum of Modern Art, Hughes asked if modernism is over. Rubin wavered. “I don’t think that it is out of the realm of possibility that a handful of great geniuses, great painters could emerge in the next 10 years and revitalize this tradition,” he said. “And that’s all it takes. Two or three men.” Rubin’s hope quickly faded as he concluded: “There is a lot of evidence to suggest that a period is ending.”

Such an “ending” comes as an elegiac conclusion to The Shock of the New, making the series more a funeral march than history lesson. But as is often the case in art history, any claims to death can be a kind of distracting illusion by those who wish to make a different point. The series’ pronouncements against the state of contemporary art were wrapped in a fear that modernism’s male-centered foundation was cracking.

A different and more compelling illusion about contemporary art, and more particularly about photography’s place in it, emerged in that winter of 1981. It came via the first show of Cindy Sherman’s “Untitled Film Still” at the Metro Gallery in SoHo. This show arrived just on the heals of The Shock of the New premier. Her second show at that same gallery followed later that year, when Sherman presented a series of centerfold photographs, each a haunting image of the young artist as she performed a psychologically rich distortion on the traditional men’s magazine imagery. At the time, Andy Grundberg in the New York Times called Sherman “a playful and political postmodernist.”

“Untitled Film Still #6” (1977)

Those were the years when postmodernism as both concept and art market was taking shape. Sherman’s photographs, with their focused attention on the female body (Sherman’s body) and their play with representations, have become iconic of the era. The decades since those first shows, Sherman has continued to turn the camera on herself. Or rather on Sherman as performer, transformed and transfixed by makeup and clothing and prosthetics, reshaping her body and face in ways that are captivating, grotesque, and ultimately arresting in their quietness. She was part of a group of female artists that included Sherry Levine and Barbara Kruger, but also the more radical work of Robert Mapplethorpe, who explored art as a performance that was both intimate and political, borrowing aesthetics from art history as much as from popular culture. Such artists reimagined what photography as art could achieve, turning it into a deeply self-conscious play on representation itself.

The current retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (set to travel well into 2013) features more than 170 of Sherman’s works from the early 1970s to her more recent large-scale murals. The show offers an unsettling and thrilling experience as you engage with the countless characters Sherman has created of herself over the years. Neither self-portrait nor documentary, her photographs straddle a space not easily defined, and gesture to a range of popular imagery from film and photography to magazine ads and popular culture icons. Perhaps because of such gestures, her images have become so significant to discussions of postmodern and feminist art (labels that too often define and confine her work), providing the subject matter for unending explorations and interpretative leaps over the years by critics and academics. “There is no Cindy Sherman,” writes curator Eva Respini in her catalog essay, “only infinite characters who reflect the countless mediated images that bombard us daily.” But beyond these questions about postmodern theories of gender and identity, this retrospective prompted a different question in my mind: How have Sherman’s photographs become their own kind of history?

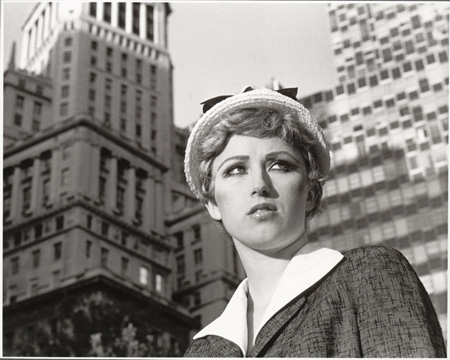

The heart of the show is undoubtedly the complete series of her “Untitled Film Stills” with their fictional scenes recalling a visual language so embedded in our cultural imagination. They hold the compositional perspective and lighting of classic Hollywood or European avant-garde films, drawing us back to a different era of modernism that was more popular culture than high art. In “Untitled #21,” the camera looks upward, capturing the protagonist’s round crisp face looking off to the side as skyscrapers rise behind her. Sherman as femme fatale offers a look on her face that betrays a lurking danger somewhere just before this shot or just afterward.

“Untitled Film Still #21” (1978)

The close arrangement of these small, 8 x 10 photographs forces you to slow and notice just how deeply haunting they really are. In their quiet uncertainty, where the protagonists (all played by Sherman) stare off into the distance, the faces of each character projects a moment of isolated despair or grief or anger. It is what each of these images gestures toward, outside the scene we see, that make them so mysterious and threatening. But as fictional “film stills,” these works draw us in not by giving us something we have already seen, but rather something we imagined we have seen — a mimesis of an imagined past and of film history itself.

This same mystery compels us in the series of centerfolds Sherman completed in the early 1980s. Commissioned by Artforum magazine, but never published, these photographs recall the traditional genre of eroticized centerfolds in men’s magazines. But Sherman remakes this genre such that its not that static, eroticized bodies of the female models that capture our interest but rather an acute emotional reality revealed in facial and body language that turns the image into a uncomfortable encounter between viewer and model, making them anything but erotic. As in the “Untitled Film Stills” series, Sherman presents these woman as caught both within the frame of the image and psychologically beyond it. In this way, they diverge drastically with the centerfold genre, which present the women for the pure act of looking, each body offered up as an object of voyeuristic pleasure without clues to the model’s emotional interiors. The longer you stay in front of these large format images, with their saturated colors and hazy atmospheres, you begin to wonder about the hopelessness of each character. Then you begin to wonder about your own place as viewer, voyeur, or, better, witness. The wall text tells us that these images make “us aware of, and complicit in, the acts of photographing and looking.” And indeed this is true.

The more you look and ponder these photographs the more complicit you feel. The more powerful works here project these questions on us, asking us to consider who we are as we stand there in front of the image. Such questions come most acutely in a series of large format photographs of grotesque outdoor settings that Sherman created in the 1990s. These images evoke colorfully arresting crime scenes that focus our attention on the details of evidence such as spilled soda, vomit, and what looks like scraps of bloody skin. The body of a woman in such images just barely makes it into the camera’s view; or, as in “Untitled #173,” is reflected in a pair of sunglasses lying on a beach towel, her face frozen in a gesture of fear. These images took me some time to comprehend, but their scale and intimacy drew me in. Then they turn the act of looking into its own unknowable reality, a puzzle that compels us until we look too long and realize the horror we just discovered. Throughout her work, Sherman plays with photography’s authority over realism, turning our faith in the medium against us like a weapon.

In much of her work, Sherman exhibits a keen skill of transforming the familiar into illusion, and the illusion into the familiar. Her series of history portraits fill a small corner gallery. These images from the 1980s recreate in style and manner Baroque compositions, with Sherman playing each of the poised figures. But her props are always visible. In “Untitled #216,” she dresses in silks and satin and holds what appears to be an infant, her one floppy prosthetic breast dangling downward. In another, the seams of her prosthetic nose are clearly visible as she sits serious-faced, looking the part of a medieval merchant, brushy eyebrows reminding us that all this is play and artifice.

“Untitled #216” (1989)

In one, dressed like a lady-in-waiting of the French court, she reclines and stares at the camera; her open cleavage shines slightly with its plastic sheen. As in her earlier works, these are not strict recreations of actual paintings from art history’s archive (though a few do indeed restage earlier works), but rather capture the mood and compositions of the earlier genres, transforming the high-art into mere grotesque performances. She borrows more than copies, always making us aware that what we are looking at is artifice, asking us to consider how all art rests on such performances of illusions and realities, and tearing away at art history’s sacred pedestal.

“Untitled #213” (1989)

In series such as “Hollywood/Hamptons,” the artifice is turned back to us — or, more precisely, to women of a certain social class. These images crowd around you in a brightly lit gallery, each photograph composed like a professional studio portrait, though as each woman sits staring at us they exude a certain fragility. Sherman uses the same exaggerated makeup and prosthetics as in the historical paintings, but now they take on a kind of pathos of identity, as if these women are just at the edge of their own illusions about themselves. Some critics have deemed these images mean. Others see them as empathetic. The range of reactions attest to the complex visual cues they inspire and question. As co-curator Johanna Burton points out in her excellent catalogue essay, these images provoke a layered encounter of meaning-making that neither rests solely in the image nor in Sherman’s camera eye, but rather in the viewer. We need to recognize, Burton writes, “our own part in creating the individuals before us” in these works. This participation in the creation of Sherman’s photographs, or any photograph for that matter, is often true. Whether they are Sherman’s haunting clown montages, the mythical series with their darker undertones, or the more recent “Socialite Portraits” with their reserved and stiff compositions of aging women, the images are pure illusion, performances that draw us in not solely by what they present us, but what they evoke in us.

“Untitled #465” (2008)

A few years ago, editors at Interview magazine asked 20 friends and colleague to pose one question for Sherman about anything they wished to know. One colleague asked if Sherman had to pick just one portrait to hang on her wall for a year, what would she pick. Her response: “Man Ray’s portrait of Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy because almost anything by Man Ray would do, but Duchamp is one of my all-time heroes.” Sherman’s selection of Duchamp in drag reminds us how much her work recalls modernism’s own play with gender and identity, not only in Duchamp or Man Ray but also the French surrealist Claude Cahun, with whom Sherman is often compared. But unlike those earlier artists, Sherman’s own form of drag performances illuminates a particularly late 20th-century spectacle that questions the artifice of gender and social identities, as much as it asks us to distrust representation itself. Sherman’s photographs evoke an idea of art as a mediated illusion, a grotesque and haunting chimera composed of different parts and pieces, of high-art and popular culture, of fantasies and uncertainties that are embedded and embodied in an array of visual cues that we encounter each day. These ideas have become our language about art and images since the late 1980s, from the art market, to the critics, to Madison Avenue and beyond.

I left this wonderfully exhausting retrospective, not with the shock of the new, to recall Hughes emblematic title, but rather the much more unsettling shock of the familiar. • 11 May 2012