It took a while for Americans to start using ZIP codes — about 15 years. 15 years of persuasion, encouragement. 15 years of re-positioning and rearranging deep-rooted beliefs about the manner in which an envelope ought to be addressed. 15 years is a long time to get used to writing five digits on a letter. And now we hardly give ZIP codes a second thought.

The United States Post Office Department knew Americans were not going to like the new system when they introduced it 50 years ago, in July 1963. Postwar Americans were being asked to memorize more numbers than ever — social security numbers, telephone numbers. The nation’s telephone company, AT&T, had recently completed their own campaign convincing Americans to use area codes. They warned the Postal Service that their task would not be easy. And area codes were only three digits; ZIP codes were five. Not only would every American have to memorize a five-digit code for their own town or city, there would be endless ZIP codes they would have to know every time they wanted to send a letter.

In the 1950s and 60s, Americans were spreading out and away from each other, into suburbs on the outskirts of cities, developing the undeveloped wilderness of the country at an incredible rate. This dispersion made mail delivery much more complicated. Before ZIP codes, letters did not move from one city right to another. Mail traveled like pilgrims, with many stops at city stations along the way. This was fine when the mail was mostly used for personal correspondence. But in the 1950s and 60s, the mail was doing more. What was once a system for sending letters and postcards became an agent for business. Advertisements filled mailboxes, and you could pay your bills by mail too. You didn’t need to get your newspapers and magazines on the street anymore — they could come to you, right in the mail. By the early 1960s local post offices were overwhelmed; postal workers were heroically bearing the heavy burden of mail. The Post Office Department imagined a more streamlined system, one that could get the mail delivered fast. With ZIP codes, machines could sort through the mail and send letters directly to their destination. With ZIP codes, the mail could be more efficient, more effective. But Americans would have to be convinced.

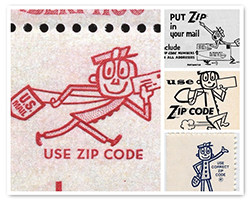

The campaign began with the name itself — ZIP. It was a good name. ‘ZIP’ sounded a lot friendlier than Zone Improvement Plan, the Orwellian phrase for which ZIP was an acronym. At the same time, ZIP said speed. Mr. Zip — a hand-drawn, wide-eyed little postal guy — became the face of ZIP code promotional efforts, the embodiment of the harmless yet zippy quality of ZIP codes. (‘Mr. Zip’ was also a significant improvement on Mr. Zip’s original name “Mr. P.O. Zone”.) Mr. Zip was speedy and clever, like other American cartoon heroes: Bugs Bunny or Speedy Gonzalez or the Road Runner. After July 1, 1963 Mr. Zip was everywhere. Americans would turn on their radios or televisions or open a newspaper and there was Mr. Zip, banging the drum for ZIP codes.

The ZIP code campaign was prolific and varied, appealing to Americans on every level possible. The word “revolution” in some campaigns appealed to the revolutionary spirit of the nation’s citizens. “This is Mr. Zip,” began one television Public Service Announcement. “He revolutionized the mail delivery system of the United States with his ZIP Code. The heart of the system is a number — a ZIP Code number.” One radio spot titled “Machine” played simultaneously to an American sense of duty and love of technological progress. It made ZIP codes sound like a method for shooting your letters right into outer space.

[Sound of machinery]

Announcer: That machine you hear is a ZIP code scanner in action, an electronic device that actually reads the ZIP code on your letters and speeds them on their way at the fantastic rate of 36,000 per hour. Put it to work for you. Use ZIP code on every letter you send. Don’t hold up the mail. Remember mail moves the country and ZIP Code moves the mail.

[Sound of machinery]

Yet another tagline appealed to the power of individual action: “Only you can put ZIP in your postal system” it urged.

As the 1960s went on, the campaign intensified. A musical television spot by the Swingin’ Six threatened that, without the use of ZIP codes, the postal service might actually explode, a pretty formidable message in the Cold War age. And what of the local postal workers, suffocating under the mountain of mail? Americans were begged to consider them.

Here is a message from the United States Post Office:

HEELLLP!!!

The lilting ‘ZIP Code Ballad’ evoked railroad workers and pioneers and drifters on the open prairie, dreaming of their faraway beloved:

[Guitar music throughout]

Singer: My true love’s many faces, many places you see; the city, the country, the sea. Wherever my true love may take it to be; now ZIP code will find her for me. Wherever my true love may take it to be; now ZIP code will find her for me. Oh ZIP code, please find her for me.

Two years after the ZIP code campaign launch, half of Americans were still not using ZIP codes.

Efforts were increased. In 1965 the Ad Council was employed. Advertisements for ZIP codes were placed on city streets, in bus and subway stations and billboards. The image of Mr. Zip became less visible in the media and more visible on the stuff of daily life. Mr. Zip was placed on toy mail trucks, jewelry, patriotic lunchboxes, mugs, thermoses, piggy banks. One year later, ZIP code use was up to 63 percent.

Postal employees were perhaps the most important instruments in the ZIP code revolution. They received detailed and weekly information in the Postal Bulletin about the new ZIP code system, its implementation and the uses of Mr. Zip promotional materials. Mr. Zip was inside every local post office, on stamps and on the sides of mail delivery trucks. Carriers and clerks were shown how to affix Mr. Zip badges to their satchels, where to affix their Mr. Zip buttons, their Mr. Zip decals, their Mr. Zip life-sized posters. The more local postal employees promoted within their communities, the faster ZIP codes would catch on. One memorandum from the Post Office Department to local postmasters (now in the Smithsonian Postal Museum Library) emphasized the necessity of grassroots efforts. “[Mr. Zip] won’t be seen on the comic pages. In fact, Postmaster [fill in name of local postmaster] says, he [Mr. Zip] is expected to perform a much more vital role in both the business and social life of the community.”

Postal workers found their own creative ways to bring Mr. Zip and the ZIP code into their towns. Mr. Zip made appearances in town fairs and parades. Community post offices held promotional dances and beauty contests that crowned a number of ‘Miss ZIPs’ across the nation. Children, the ZIP code users of tomorrow, were given Mr. Zip cartoons at school. In the mid-1960s, the Post Office Department initiated a ZIP Code Week in 12 American cities. The experiment was successful. In 1966, President Johnson signed a ZIP Code Week Proclamation. “The… document before me,” he pronounced, “concerns the ‘spontaneous cooperation of a free people.’ It is a proclamation designating the period of October 10 through October 15 as ‘National ZIP Code Week.’ I am convinced,” said the President, “that the ZIP code has done more than any other recent innovation to move our postal service out of the age of the horse and buggy.” This time, 302 cities joined in the festivities: businesses, church groups, women’s clubs, and civic organizations. The ZIP code was no longer just an identification number — it was a pop culture phenomenon, with Mr. Zip as its icon.

ZIP code use rose further. By 1968, 75 percent of Americans were using ZIP codes. By 1969, the figure was 84 percent. By the late 1970s, the majority of Americans were putting ZIP codes on their mail as if they always had done so. Little by little, Mr. Zip was phased out. And then, he was gone.

With the exit of Mr. Zip, ZIP code training was complete. And still there remained the question of why it took so long. For 15 years many thousands of American letters were dropped into mailboxes without ZIP codes, even in the face of a ubiquitous ZIP code gospel. Americans were mostly convinced that ZIP codes were helpful, and still they could not write them. The Post Office Department knew the blank space that persisted after an addressee’s name, street, and city was a small and quiet defiance. Of what, though, they could not say.

•

The 20th century was the time of the Great Numbering. It was in the 20th century that Europeans and Americans learned to locate themselves through numbers. The story of ZIP codes is just one story in this transformation. ZIP codes put numbers on places and told us where we were — in a part of the Midwest in the United States (6), in Chicago (06), in Elmwood Park (39). Then, they started to tell others who we were. ZIP codes are now connected to other numbers, and those numbers are connected to each other. Insurance and credit card companies use ZIP codes to decide if we are trustworthy. They are used to find our politicians and for our politicians to find us. We use our own ZIP codes at the gas station to fuel up before our journeys and other ZIP codes to map them. Our numbers, in part, have come to identify us. We live within a labyrinth of numbers.

Sometimes the labyrinth of numbers carries an air of fun, mystery, even hope. Consider, for instance, the phone number. Phone numbers were connected to an exciting new technology that allowed people to communicate in a completely new way — in real time across cities, across the world. Ships could talk to each other from sea to sea, children could talk to soldiers. Phone numbers became inseparable from romance — the phone number was a prize, a promise of a love affair to come. A phone number on the bathroom wall was a mental dalliance with unwholesome and titillating activities. We could have a direct line to heaven or hell. And how many songs have been written for telephone numbers? Pennsylvania 6-5000. Beechwood 4-5789. 867-5309. 6060-842. 634-5789 — If you need a little huggin’.

ZIP codes were never romantic. You certainly never saw ZIP codes on a bathroom wall. ZIP codes didn’t seem to give us anything novel or mysterious, didn’t expand us. They made communication faster but not necessarily better. Artists never stopped musing about the mail, but they sang of letters, or the postman, or the postal service. Unlike telephone numbers, ZIP codes were the attempt to improve a form of communication that had already existed for hundreds of years — thousands of years. The conveniences that came along with improved mail service were obvious. Americans were happy that their mail traveled faster and got lost less. They liked paying their bills without going to the bank, getting their newspapers without going to the street. But these conveniences not only changed how people shopped and read. They were physical and social transformations. ZIP codes subtly changed how we move around our neighborhoods, how we find each other, how (or if) we talk to each other. ZIP codes made location easier when it came to the mail. But they left a lingering trail of dislocation behind them that was less easy to define.

The heart of the system is a number, Americans were told, a ZIP Code number. But they couldn’t find ZIP code’s heart. There is, after all, something uneasy in Mr. Zip’s crooked stance. He leans precariously on his fragile legs — they are too fragile to move so fast. His staring eyes are crazy and lidless — can Mr. Zip close his eyes to dream? He has but one ear and his mouth is a line. Mr. Zip smiles but cannot speak. Could anyone trust this racing eggshell of a man, who can hardly sit or stand, to be our steward, our beacon in the dark? Even back in 1963, there were those who suspected that Mr. Zip was a herald of changes so profound as to be beyond our control. “Mail moves the country and ZIP Code moves the mail.” Indeed. But moves the country where? Toward what? And why? Mr. Zip had no answers. He was moving too fast to stop and chat anyway. • 12 June 2013