Ralph Eugene Meatyard is a marginal figure in the history of post-World War II photography. He took up the practice in the early 1950s, maturing his creative vision until his untimely death in 1972 at the age of 47. This marginal status is due in part to the kind of photographs he made, which are difficult to categorize or to make sense of. “I will never make an accidental photograph,” he once said, noting his distance from documentary photography, the more respected genre of his day. His images are always staged compositions of family and friends or of simple objects. He presents haunting images that sit somewhere between realism and imagination. Meatyard positioned his subjects in stark interiors, lush forests, abandoned homes, and overgrown cemeteries, settings he went searching for around his home in Lexington, Kentucky.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art’s small show of a little more than 40 works confronts you with the particular theme of Meatyard’s obsessions during the 1950s and ’60s. While odd props such as rubber chickens and the body parts of soiled dolls fill many of his works, it is the dime-store Halloween masks depicting crones or hoary men that give his work a strange, grotesque feeling. These masks, on both children and adults, conger and unsettle a trope so dominant in our thinking about photographic portraits. The mask itself has been used by photographers from early in the medium’s history — the playful masked portraits of Countess de Castiglione in the mid-19th century or Man Ray’s surrealist compositions of pale European faces next to wooden African masks in the 1920s, for example. But the metaphor of the mask has become a compelling rhetoric about photographic portraiture, particularly within celebrity culture: Richard Avendon took his candid portraits of Marilyn Monroe at the time Meatyard took up photography. Meatyard plays with this tradition as his images prefigure a kind of photography that makes us wonder about the image itself, about the illusions that photography can create. “The mask is no man,” he once declared, adding, “everyone has a mask on.” His images confront us with masks that erase more than hide, that turn us outward instead of drawing us in toward the psychology of his subjects. Without Meatyard it is hard to imagine Diane Arbus or Cindy Sherman or Duane Michaels, or even some of the portraits of Robert Mapplethorpe.

When Meatyard took up the camera in the early-1950s, documentary and social realism were dominant genres for the camera’s serious use. Think of Robert Frank’s iconic collection “The Americans,” published in 1958, with its spontaneous moments of captured street scenes presenting subtle layers of lyricism. “The Americans” depict the regional particularities seen through Frank’s travels around the country, turning the social landscape of 1950s America into a kind of sad dream. The series has become an icon of post-World War II photography, and the immigrant Frank a kind of visual poet of the era.

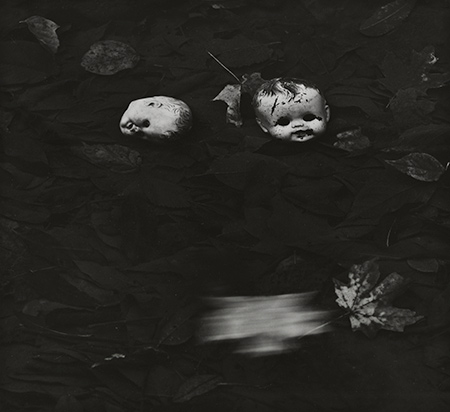

But Meatyard’s more intimate, shadowy scenes offer a surrealist quality, an intimate, local exploration that conjures larger meditations, what he sometimes called “romantic-surrealist.” Here there are children sitting in fields, or leaning against weathered barns, their tiny bodies casual under the aging masks they wear. We find bruised and soiled doll heads that float in the waters or linger on tree limbs. In one sequence, an adolescent boy wearing a mask of an old man sits on a log, his body relaxed as it faces the camera. In the next photograph, the boy bends forward, knees slightly bent, the top of his head faces us as he holds two masks in each hand. In the final images, only the masks remain, propped against the log that stretches into the nearby pond; the background blurs with watery reflections.

“Untitled” (ca. 1962)

Throughout his work, Meatyard used his family members and neighbors to pose for him, putting them in barns; near abandoned homes; in forest groves overgrown with native ferns, dogwood trees, honeysuckle shrubs, and bittersweet vines with their poisonous fruits. His scenes feel so purely Southern Gothic they look like they emerged from the pages of Flannery O’Connor, or some of the later stories of William Faulkner. Indeed, O’Connor’s writings would be the inspiration for his last, and best-known, series of photographs “The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater,” a collection published after his death.

“Untitled” (ca. 1968)

But gothic or grotesque, two terms that are often used to describe Meatyard’s work, only get at part of the intrigue and power of these images. While summer workshops taught by Henry Holmes Smith, Aaron Siskind, and Minor White influenced his ideas, Lexington writers Wendell Berry, Guy Davenport, and James Baker Hall influenced Meatyard’s vision and aesthetics. They formed a small circle of thinkers and artists against the background of a changing South. Meatyard’s photographs are strongly narrative in their composition and staging, turning toward imagined worlds that linger on the margins of reality. While the social realists turned the familiar into the strange, Meatyard’s photographs so often turn the strange into the familiar.

Meatyard, born and raised in Illinois, served in the Navy during World War II, studied for a time at Williams College, before moving to Lexington, Kentucky to work for an optical firm. In 1967 he opened his own optician shop, called Eyeglasses of Kentucky. Perhaps it was his experience as an optician that fostered Meatyard’s interest with how the lens can distort, shift, and turn reality into something unrecognizable. Perhaps this is why his work straddles the divide between realism and surrealism. The dolls in particular float through these photographs as both props and subject matter. In three particular photographs, Meatyard fills the frame with the chipped and damaged head of three different dolls, all decapitated and sitting on wooden planks, their eyes emptied and shattered, though their faces still hold their shape. In other images, dolls float in the forest vegetation or along shallow pools, and we wonder what they are doing there. They look so discarded, so much the refuse of some other time and place.

The photographer also used mannequin heads, taken from the storefronts of women’s clothing stores. He rests these in darkened woods or sticks them in decaying stairwells. These images contain so much decay, so much that is distorted by the past, by history. Even the masks hold this odd juxtaposition between past and future. Those large, aged heads of men and women on the bodies of children conjure a quite haunting split between youth and old age, fused together in unsettlingly ways. His subjects are so often caught in this moment between past and present, between a decaying history and a youthful future.

“Untitled” (ca. 1962)

Meatyard remained quite reticent to discuss his work. In her catalog essay, historian and exhibit curator Elizabeth Siegel notes that the photographer encouraged viewers to bring their own interpretations to his images, which, for Siegel suggested the ways his photographs “tended to function as Rorschach test for his viewers.” For her, these photographs of masked children and adults strip away the individuality of any one person, turning the cast of characters into actors who represent something lager. “A mask served to level identity,” she writes, “and erase differences so that viewers could approach a picture with a shared sympathy.”

But we don’t need to universalize these images to grasp their force. It’s true, the metaphor of social masks is a powerful one, the notion of life as its own everyday performance a running current in contemporary life. This was an idea floating in the air as Meatyard went tramping through the woods with his children in tow, masks and dolls in bags. In 1959, Erving Goffman published his now canonical work The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, which pointed to the ways our most basic interactions are part of a larger theater of social relationships. Our very identities were now subject of the vagaries of performance. All that we thought true about ourselves and those around us needed to be viewed with a more suspicious eye. Meatyard knew this as well.

But Meatyard was developing his aesthetic vision of photography’s staged realities amidst the conflicts and violence of the civil rights movement. Let’s remember what was happening in the years when he took up his camera: The Supreme Court’s abolishing segregated public schools (1954); bombings in Louisville, Kentucky in response to segregated housing laws (1954); the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott (1955-1956); sit-ins at lunch counters that began in 1961; church bombings and protests in Birmingham, Alabama (1963); the March on Washington (1964); and voter registration drives of Freedom Summer (1964). These events all swirl around Meatyard’s photographs, turning the trope of Southern gothic into its own haunting past, portrayed in gnarled masks, decaying dolls, limbs floating in trees.

These photos do indeed erase differences. They create the “no man” that Meatyard claimed. But they also acutely point to a time and place that was changing. His images play with our sense of reality to turn what we think as inherent truths into frightened fantasies about other people. If the masks conjure a universal humanness, they also remind us how much they deny. • 12 July 2012