“The great fact of England’s recent culture,” writes curator and art historian T.J. Clark in the catalog to this show, “is how little the landscape and social fabric of industrialism have been allowed to appear in it.” This fact, Clark reminds us, has created a history of English painting that rests on the “cult of the countryside, the comedy of upper-class manners, the dull decencies and resentments of the new middle classes, the lure of London, the grandeur and ambiguity of Empire.”

- Lowry and the Painting of Modern Life

Tate Britain, London.

Through October 20, 2013.

L.S. Lowry’s paintings stand against this history. These canvases offer us a perspective of the industrial landscape dominated by the low eaved houses, brown and ochre hued, set against the towering factory and mill facades, their piercing smokestacks billowing black plumes. Lowry’s people, rendered in slight, nearly stick-figure fragility, seem so very small amidst the geography they inhabit.

The anomalous nature of these works attest to Clark’s claim about English painting. Just walk across the hall from this show to the Tate’s recently reorganized permanent collection entitled “A Walk Through British Art” and you will see the catalog of upper-class portraits and middle class concerns, and everywhere you encounter the bucolic vistas of the English countryside. The one Lowry painting on this walk is entitled “The Old House, Grove Street, Salford” painted in 1948 depicting the simple grandeur of a Victorian house in the city’s more fashionable middle-class neighborhood. The house’s façade serves as a backdrop to three faint figures who promenade along the stark white sidewalks, the pavement clean and empty, not a smokestack in sight.

So this show, the first major retrospective of Lowry’s landscapes since his death in 1976, confronts you with the unfamiliar. Both in their simple, naïve style and the nearly obsessive, repetitive panoramas, these paintings remind us of modern painting’s blindness to the working class. While there were painters on the other side of the Atlantic who captured intimate moments of working class life (think John Sloan’s Lower East Side or William Glackens’ Greenwich Village of the early 20th century), for the most part, the industrial realities of American modernism were left to the photographers such as Jacob Riis’s documents of overcrowded tenements, or the toil of the factory floor in the photographs of Lewis Hine. In reconsidering Lowry’s industrial landscapes within the history of English art, this show compels us to consider what painting can show us about the realities of the working class.

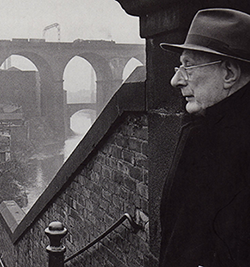

Lowry was a child of Lancashire in England’s industrial north. He rarely left that geography even as his paintings were being exhibited in London, and more often, at the Paris Salons in the 1920s and 1930s. It was in those Salons that the French critics saw in his work themes that connected to modern French painters, particularly in his rendering of scenes from everyday life.

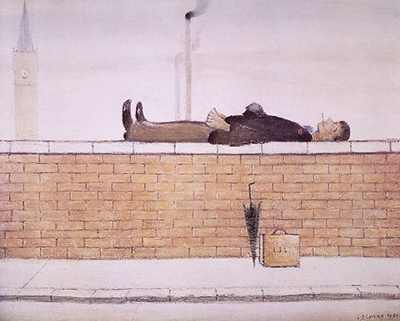

“Man on the Wall,” courtesy of Robert Wade, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

But despite these showings, Lowry remained an outsider to the avant-garde circles of both London and Paris, working most of his life as a rent collector for the Pall Mall Property Company in his native Salford near Manchester. Few in the art world knew of his day job, walking (he never owned a car nor a telephone), through the streets and alleys on his weekly rounds, and, one can imagine, encountering scenes and geographies that would spark his painterly imagination. What Lowry gives us in these works is not actual places or encounters (his paintings are often have generic titles such as “Industrial Town” or “View of a Town” or even “People Standing Around”), but rather imagined landscapes, pieced together with buildings and crowds that would seem both familiar and strange to his contemporaries. He painted both the mundane moments of going to work as well as moments of play: football matches and town fairs. But these events are always ringed by the larger environments of drab housing and the seemingly endless smokestacks that, in most cases, rise even higher than the church steeples.

In an interview done a few years before his death, he noted his motivation for his subject matter: “I wanted to get a certain effect on the canvas. I couldn’t describe it, but I knew it when I got it. Well, a camera could have done the scene straight off. That was no use to me. I wanted to get an industrial scene and be satisfied with the picture.” Inherent in this claim is the particularly subjective vision Lowry’s was after, creating works that were as much personal as they were social.

In the early 1920s, Lowry attended classes at the Manchester School of Art and studied under the French Impressionist painter Adolphe Valette. It was Valette who introduced Lowry to the techniques of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, and encouraged the artist’s task of composing canvases of from scenes of everyday life. And it is this influence that anchors the first half of this show, situating Lowry’s Lancashire alongside Pissarro’s London or Van Gogh’s Paris. These comparisons seemed a stretch, for Lowry’s works reject the subtleties of color and light, reaching instead for more precise hues and shapes.

Near these works, you encounter a quote from Charles Baudelaire’s review of the 1845 Paris Salon, which began his series of essays that encouraged young painters to capture scenes of modern life. Baudelaire excites the artist to see “how great and poetic we are in our neckties and patent leather boots.” It is an odd connection between those details of clothing and fashion and Lowry’s landscapes. Many of the French painters depicted landscapes of atmospheres and created portraits of the city’s rising middle class, festooned in the latest fashion, who, in turn, became the reliable consumers of their own image. There are of course few neckties and leather boots found in Lowry’s lots. His scenes were of the places and people who made such things.

“Industrial Landscape,” (c. 1955) Courtesy of the Tate Britain.

You begin to realize how the subject of the working classes may not fit this flow of art’s self-image, this modern life that was emerging beyond the taint and soot of the industrial landscapes that made modern life possible. Perhaps Edgar Degas, who created a few paintings of women ironing clothes or sewing hats, all captured in darkly hued canvases that gave their subjects the same intimacy he created for the ballet dancers, is an exception.

Lowry’s paintings are rarely intimate and instead take a more sociological vision. We encounter his scenes from a distance, perhaps reflecting his own place in these neighborhoods as the weekly rent collector. He composed these landscapes like a stage set, conjuring the reality that working class lives, by the very overcrowded conditions of their domestic worlds, were so often lived in public. This distance compels a sense of mysteriousness about these lives, at the same time as it presents them on the canvas for us to consider. There is no pretense that Lowry or the spectator can really know anything about these scenes beyond our spectator view.

And this is the compelling quality of these works, in showing how the private lives of the working poor were so often spectacles of public concern. In “The Fever Van” (1935), we stare down a narrow street as a crowd gathers behind an open ambulance. We stand at a distance, on one of the outer circles of spectators caught in doorways, on the corner, men and women, even children strain to watch the event. We can only see the backs of people off in the distance, and the moment provokes perhaps an odd voyeurism. The whole scene plays out under the heavy gray church steeple and factory smokestack that lie at the center of the paintings vanishing point, framing the personal tragedies within the context of the entire town.

“The Fever Van,” (c. 1935). Courtesy of the Tate Britain.

“The Removal” (1928) does this more acutely, as Lowry renders the scene as if looking from a faraway rooftop, we look down upon a small crowd huddling along a back alley, rows of tenements just behind them, furniture abandoned in the snow. Beyond the small group, others look on, steady and frozen. A family is being evicted. The rent well overdue. Off in the distance of a soupy fog is the precise rectangle of the factory, its several smoke stakes billowing dark plumes, putting a heavy weight on this eviction. We want to get closer, to see these people, to hear them, but Lowry doesn’t give us this.

Amidst this distance is a silence that permeates these canvases. In “The Empty House” (1934), the buildings reddish exterior and Georgian stoicism anchors a haunting scene where a few trees stand bare along a flat landscape, a murky pond in the foreground intensifies the mystery of the place. It reminded me of a Hooper painting, the utter stillness of the moment leaving me to wonder what is behind those windows. But even in the street scenes such as “People Going to Work” (1934) or “Returning from Work” (1929) or “Coming from the Mill” (1930), there is an isolating stillness that surrounds so many of those fragile figures bent forward, moving along alone. You begin to wonder about their lives. The more you look at these paintings the more you realize how much they rest on mysteries.

“Coming from the Mill,” courtesy of mmrobertwade, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Perhaps this is why you encounter other ways of “seeing” the working class in Lancashire throughout the show. There is a series of short, black and white film loops from the early 20th century of workers at a protest march and another of colliers returning from the mines, their faces nearly black with soot. What I was struck by was how aware they are of the camera’s eye, the men and women bunch together in tight crowds to look at us as we are looking at them a century later. At one point during the protest march, the people start waving, and you can almost here the cheers and voices of the scene even at this historical remove.

Later, you encounter an excerpt from George Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier, his 1937 account on the conditions of the working-class in Lancashire and the North Midlands. Orwell immerses himself and us in a world of ruin, rendered with poetic insights that present what he calls the “lunar landscapes,” detailing a region “from which vegetation had been banished; nothing existed except smoke, shale, ice, mud, ashes and foul water.” Against such archival and documentary images and narratives, Lowry’s paintings take on their own historical importance that slips quite easily into nostalgia.

“Piccadilly Circus,” (c.1960). Courtesy of the Tate Britain.

Lowry himself turned increasingly towards nostalgia in the years after World War II, when he retired from his position at the Pall Mall Estate Agency. In his later works there is little of the post-War era, with one exception: a rare painting set in London’s Piccadilly Circus, the flow of people and traffic displayed with Lowry’s distinctive hues and forms, but instead of factory facades looming in the background, it is the visual noise of commercial culture, most notably the American icon of a Coca-Cola sign flashing above the double-decker buses.

“Going To The Match,” courtesy of mmrobertwade, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

More often, Lowry works imagined a 19th century past. In a series of large scale canvases done in the early 1950s each presenting a near-bird’s eye view of an industrial town, the people become mere flecks amidst expansive hills where low roofed houses mixed with those rectangular mills and factories, each entire scene looking as if it is being held up by those smokestacks like long fish hooks. These canvases evoked for me the intricate vistas of Flemish painter Pieter Brugel, where social life, geography, and the built environment all play a part in the painting’s drama. There is something utterly serene in them, the shapes and colors nearly in harmony, turning Orwell’s ruins into its own kind of beauty.

“These paintings are about what has been happening to the British economy since 1918 and their logic implies the collapse still to come,” wrote art historian John Berger in a 1966 essay on Lowry. Berger was quite prophetic in this essay, concluding that the coming collapse will be anchored to England’s “shift of power from industrial capital to international finance capital.” Today, Lowry’s paintings offer nostalgic landscapes, reminding us what has been lost in the last half-century, more than what was. Strangely, their distance so often leaves us admiring the views.

In the gift shop, next to a display of books on the working class, including Orwell’s study of Wigan, and Frederick Engel’s The Conditions of the Working Class in England, published in 1845, I found the usual memorabilia of museum objects: refrigerator tiles, mugs, and tote bags, each displaying scenes of Lowry’s workers, those fragile inhabitants going to or from the factory. But oddly the museum was also offering specially designed cufflinks, silver framed squares depicting a detail from the painting, “Going to the Mill.” To match these were yellow silk ties with the same detail of those isolated workers bent forward in their morning routine. I thought about Baudelaire’s “neckties and patent leather boots” and tried to imagine those workers in some other country who labored at transforming Lowry’s mill workers into these fashionable objects of modern life. • 17 July 2013