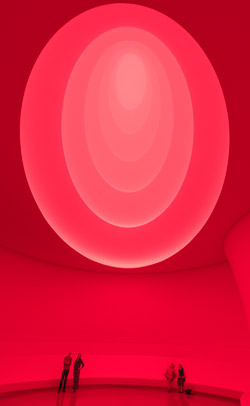

There is an egg in the middle of the universe. Sometimes the egg contracts. Sometimes the egg expands. Sometimes the egg fades away completely, though a hazy aftereffect of the egg-that-used-to-be hovers in the eye (or mind). The light around the egg changes slowly. In the beginning it is a soft white. Over time, you realize that hints of pink have crept in. Then it is violet, and blue, and rose, though not necessarily in that order. It is hard to remember the order of colors. They come and go as the egg contracts and expands. Your conscious mind does not always register the change in color until after the fact. The colors are pastels. Calm. Soft. The egg glows and hovers in the middle of a field of mesmerizing color.

- James Turrell, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New

York. Through September 25, 2013.

The spell is broken when the guard finally says, “Everybody up off the floor.” We’ve all been lying on the floor of the Guggenheim Museum in NYC, the famous spiral building. The artist James Turrell has transformed the spiral into a giant art installation. The openings between the floors are covered with fabric. Hidden lights project color. Turrell calls the work “Aten Reign.” It is museum as light sculpture.

James Turrell has been working with light for a long time. He was part of the Light and Space movement that came out of Los Angeles in the 1960s. Those were the heady days of Minimalism. It was a time when artists were dissatisfied with art objects. They didn’t want to make traditional paintings or sculptures. They’d rejected the idea that art should try to represent what we see in the real world: sky, trees, buildings, people. They were even tired of abstract work in painting and sculpture. Why, they asked, do we make paintings and sculptures at all? In 1965, Donald Judd wrote an influential article called “Specific Objects.” He wrote, “Painting and sculpture have become set forms. A fair amount of their meaning isn’t credible.” Think of an austere abstract painting that shows a black cube on a pure white surface. Judd thought the painted cube wasn’t credible because the cube isn’t really a cube; it is paint on a surface pretending to be a cube. The artist has painted the cube because that is what abstract artists are supposed to do, make abstract shapes with paint. Judd didn’t like this kind of pretending. His answer was to start making actual cubes, wood boxes that were every bit the cubes they were pretending to be.

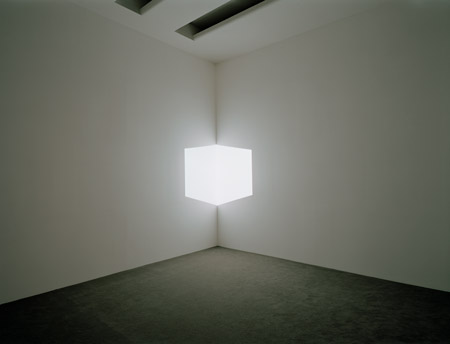

James Turrell had a related idea about light. Painters are always trying to reproduce the effects of light in their paintings. Think of one of Caravaggio’s great glowing paintings. The painting almost seems to generate its own light. Except that it doesn’t. Turn off the lights in the room, and the Caravaggio is as black as everything else. Turrell didn’t want to make another artwork that simply reflected light. He wondered, “Can the light itself be an artwork? Can you work with light in the same way you can work with colored pigment, or wood or iron?” Turrell conducted some very simple experiments that seemed to confirm that one could, in fact, make works of art with light alone. A few of these early experiments can be seen in the back rooms of the Guggenheim. In one, Turrell has projected a square of white light into the corner of a room. When you enter the room and look at the light, the square seems to be three-dimensional, even though it is not. The square of light seems to take on actual volume. What Donald Judd did with pieces of wood, Turrell did with light in a darkened room.

Afrum I (White), 1967

Now, you might say, “All of this rejecting traditional art objects and playing around with pure form is well and good. Someone probably had to do it. And that’s why we had the 1960s and 70s. Get that stuff out of our collective system. But is there any greater point or purpose to these formal experiments?” Good question.

Turrell had similar questions about what he was doing. Creating optical illusions with light was perfectly satisfying for a time. But there was always a danger that the light tricks would become gimmicky. Turrell was aware of this fact. He deepened his studies of light over the decades. He became a craftsman of the substance of light. He learned more and more about how light behaves and how subtle differences in light can create emotions in the viewer. Through these experiments, Turrell never strayed from his root intuition, which is that light is inherently meaningful. In an interview with Richard Whitaker, James Turrell explained his relationship with light like this:

I was out in a garden when I was a child, and things took on a life and a luminance that was like this near-death experience, with eyes open. Then once, in Ireland I was coming in a boat, in from Fastnet toward Whitehall. It was absolutely still. A silver light came about that bathed everything. This was an experience I had in a conscious, awake state.

Most of these experiences that people talk about are generally in altered states that are like a dream, or at least, like a daydream.

I would like to have the physicality of my light at least remind you of this other way of seeing. That’s as best I can do. It’s terrible hubris to say this is a religious art. But it is something that does reminds us of that way we are when we are thinking of things beyond us.

It would help at this point to mention that James Turrell was raised as a Quaker. So, religion is playing a role in his art, if indirectly. To understand Turrell’s art then, it is necessary to have some familiarity with what Quakers do. Quakers worship by getting together and having a meeting. All you need is two Quakers for a meeting, but Quakers are happy to get together in larger groups. Quakers conduct their meetings by sitting silently, usually for about an hour. Talking is allowed, but not encouraged. You talk if you are moved to talk. Otherwise, you sit quietly. It is fair to call this meditation. While Quakers are meditating, they seek what they call the Inner Light. The idea of Inner Light goes all the way back to the early 17th century and to George Fox, the very first Quaker. As a young man, George found himself displeased with religion in its contemporary form. He struggled to find the truth, as sensitive young men and women will do. These were years of darkness and tumult. And then he found peace. In 1647, George heard a voice that said to him, “There is one, even Christ Jesus, who can speak to thy condition.”

Fox remembered that Christ sometimes calls himself “the light” in the Gospels. He decided that light was the key to correct and meaningful religious practice. There is a light inside of all of us, he thought. When you connect to the light, you are also connecting to God. For this reason, Quakers aren’t all that jazzed up about specific religious doctrines. If you are wondering what to do, how to live your life, just sit quietly and try to listen to the Inner Light. That’s all the doctrine any good Quaker needs. The answers are there inside, because God is inside.

Everybody who comments on the work of James Turrell mentions the Quaker stuff. It is impossible not to, especially since Turrell considers himself a practicing Quaker of some sort or another. (He has said in any number of interviews over the last decade that he was a Quaker, then he wasn’t, and now he is again.) For Turrell, as for any Quaker, the central purpose of worship is to find the Inner Light. The direct connection between Turrell’s art and the practices of Quaker worship are obvious.

So obvious, that I’d like to suggest that the best way to approach and interpret Turrell’s installation at the Guggenheim is to say it is a Quaker meeting. Observe, if you will, what happens when people enter the ground floor of the museum. They stop and look up. They see that the spirals of the Guggenheim have been transformed into a glowing light installation. They roam around for a minute or so looking up. Then they find a space to lie down on the floor. Generally, they stop talking. They watch the glowing lights and the luminescent egg. This silent watching goes on for many minutes. More than ten minutes. More than fifteen minutes for many people, and more than that for others.

In other words, James Turrell has managed to get people in New York City to lie on the floor silently meditating for more than ten minutes. Most of these people have never meditated in their lives. Many of them would not sit still silently for ten minutes if you paid them to do so. But the power of the egg compels them. Critics like to complain that the talk of Inner Light is so much mumbo-jumbo. Roberta Smith, in her review of Turrell’s “Aten Reign” for The New York Times teases that, “With his Old Testament white beard and Conservative Quaker background, Mr. Turrell sometimes seems a bit too much like a mystical seer.”

But for all Roberta Smith’s teasing, it is Turrell who gets the last laugh. Smith was compelled to lie down on the floor and stare up at the glowing egg just like everyone else. She participated in Turrell’s Quaker Meeting whether she realized that’s what she was doing or not. It doesn’t matter, in the end, whether the people who view “Aten Reign” believe in Turrell’s Quaker God. It is not even clear exactly what are Turrell’s beliefs regarding this God. The point is to sit or lie down and submit to the light. If you allow yourself to stare at that light for a few minutes you will inevitably have some experience of meditation. You will enter a quieter, more contemplative space. The light will do its work. An experience will occur. The instinct for many of us is immediately to speculate about the nature of this experience, to wonder whether contemplating the light is connecting to forces that are “beyond us.” But that is already to leap out of the experience in the attempt to make sense of it. Isn’t it enough that staring at a glowing light has completely changed your day? I walked out of the Guggenheim Museum feeling slightly heavier, as if the light added just a fraction more mass to my skeletal frame. The trees in Central Park swayed, ponderous, in a lazy breeze. The human beings all around me moved more slowly, even in their speed. Their faces were portents, though I know not of what. A bird flew across the street landing clumsily on an overhead wire. That just happened, I thought, and I am here. How strange, how sad, how wonderful. • 29 July 2013