You’ve heard the story about the princess and the frog. A rather frivolous young princess is playing with a ball. She loses the ball in a pond. A talking frog helps her retrieve the ball on the condition that she takes him home. The princess gets her ball and promptly runs away from the disgusting frog. Later, the frog shows up at the castle and explains the wretched behavior of the princess to the king. The king scolds the princess and commands her to be nice to the frog, who fulfilled his part of the bargain. The princess, rebuked, kisses the frog. The frog turns into a handsome young prince. The two live happily ever after.

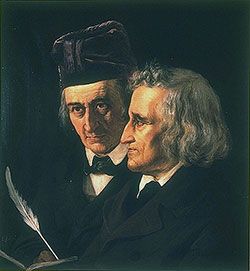

The story of the princess and the frog is an old folktale. The story made its way into modern consciousness because of two German brothers in the early 19th century. These are the famous Brothers Grimm. This year marks the 150th year anniversary of the death of the eldest brother, Jacob. Throughout their lives, the Brothers Grimm collected old German folktales. They published a volume with dozens of these stories in 1812. The very first story in the collection was the one about the princess and the frog. The collection was a huge success. It was translated into many languages, including English. The collection contained such now-famous tales as “Rapunzel,” “Hansel and Gretel,” and “Cinderella.” That’s to say, the Brothers Grimm collected and made famous some of the most universally recognized and shared stories of the Western (and now globalized) world. No small accomplishment.

We’ve created a collective image of the Brothers Grimm as kindly fellows looking after children at bedtime. But the Brothers Grimm were not concerned primarily with bedtime, nor were their fairytales the stuff of sweet dreams and childhood fantasy. Indeed, in the original Grimm version of the story about the princess and the frog, there is no kiss. The frog keeps demanding to get into bed with the princess until the princess finally dashes him — bang! — against the wall in disgust and frustration. Instead of splattering, the frog transforms into a prince.

If the Brothers Grimm were not trying to tell charming bedtime stories, what were they trying to do? Why are the original versions of their stories so often violent and disturbing? The first answer to these questions is that the Brothers Grimm were simply being true to the stories as they existed in the early 19th century. The Brothers saw themselves as faithful recorders of a living German tradition. They wanted to preserve these stories in their true and exact form. The second answer is this: The violence of the folktales is part of their power. The Brothers Grimm understood this fact. They wanted to tap into that power. They thought that the tales would revitalize a German people fallen on hard times. But we leap ahead of ourselves.

The story of the Brothers Grimm begins in a small town, Henau, in what is now the western part of Germany. But Germany was not yet a country in 1785, the year when little Jacob Ludwig Carl Grimm was born. Germany was a disorganized collection of principalities and fiefdoms. And Germans were still recovering from the Thirty Years’ War, which had wreaked much havoc in the middle of the 17th century. It is impossible to explain the Thirty Years War briefly or clearly. Let’s just say that the War left many regions of Germany devastated, depopulated, divided and unstable. It was a condition that would continue through the 18th century.

In the early 19th century, just when it seemed that Germans might be coming out of their funk, Napoleon came along. Young Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were to see their region turned into a French satellite state in 1806. At the time of the initial publication of Grimm’s Fairy Tales, the Brothers Grimm were living under a kind of military occupation.

The Brothers Grimm (as well as many other German-speaking persons at the time) found this situation more or less intolerable. And that is the context from which the Grimm project of collecting folktales must be understood. They were collecting folktales to find themselves. They were searching for their roots as a people who share a specific language, German, and a set of customs and traditions. They were looking for stories that could provide some kind of identity, some foundation. From this foundation, the German character could be rebuilt after so many years of chaos and dissolution.

In the project of building a national identity for Germans, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm published a number of books during their lives. As the Brother Grimm, they published a book called Old German Forests and another called German Legends. They also published a massive, multi-volume German Dictionary (finished after their deaths). On his own, Jacob published a four-volume German Grammar, a volume on German legal antiquities, a two-volume collection of German mythology, and a two-volume history of the German language. Wilhelm published a book on German runes and a collection of German heroic legends.

Clearly, the Brothers Grimm felt strongly about the German language. They felt strongly about the history of that language, and they felt strongly about the stories, myths, and legends that have been told by German-speaking people over the centuries. The Brothers Grimm believed that the German language had the power to teach German people who they really were. You could say that the publication of Grimm’s Fairy Tales was a political act. That’s why the Brothers Grimm have often been accused of being early forerunners of a German nationalism that eventually turned into Nazism.

Whether or not those accusations are justified, the Brothers Grimm saw folktales and legends as absolutely essential material for the formation of any kind of cultural identity, good or bad, fascist or anti-fascist. The Brothers Grimm believed that folktales are fundamental. That’s because folktales and legends express root fears, anxieties, wishes, passions, desires, and regrets. Reading the folktales of a specific people is like reading an individual’s private diary. It is not that the diary is necessarily truer than, say, the person’s public correspondence. But the private diary is certainly more raw and less filtered. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm felt that the German people would wake up to themselves if given the opportunity to read their own collective diary.

That’s why the stories in the original volumes of Grimm’s Fairy Tales are so often dark, violent, and even difficult to understand. Take the famous story of the frog and the princess. The frog disgusts the princess. And yet, the princess is obliged to the frog. In the first Grimm version of the story published in 1812, we are told that the princess “was afraid of the cold frog and did not dare to even touch him, and yet he was supposed to lie next to her in her bed; she began to cry and didn’t want to at all.” Some sort of root sexual fear is being expressed here, is it not? On one level, it is the repugnance that every virgin feels at some time or other, the repugnance of physical violation. At the same time, the princess is exhibiting defiance toward the contractual obligations of marriage. The king (the father) continually emphasizes that the princess must do what the frog asks because she made a deal with the frog when he rescued her ball. The king says, “What you have promised, you must keep. Go and let the frog in.” Every time the princess revolts, the king commands her to honor her promises. The princess, “had to do what her father wanted, but in her heart she was bitterly angry.” Finally, the princess picks the frog up gingerly with two fingers (is there some phallic imagery here?) and then dashes him against the wall with the words, “Now you will leave me in peace, you disgusting frog!”

Magically, the frog transforms into a prince and the two “fall asleep together with pleasure.” The next day, the prince’s servant Heinrich takes the two lovers back to the prince’s castle in a carriage. As they drive away, they hear a loud crack and think that the carriage is falling apart. But Heinrich informs them that the noise was only the snapping of the iron bands around his heart. Heinrich put the bands there to keep his heart from breaking when the prince was first turned into a frog. Now that the prince is “redeemed and happy” the iron bands are snapping away from Heinrich’s heart.

It is likely that you’ve never heard the part about Iron Heinrich and his heart bands. In most modern versions of the story, Heinrich is left out altogether. It certainly seems like a strange non sequitur cobbled on to the end of the story. I suspect, however, that the Brothers Grimm were particularly happy to include the part about Iron Heinrich for the reason that Iron Heinrich harkens back to a 12th century Middle High German epic poem called Poor Heinrich. Poor Heinrich was a knight who contracts leprosy. This makes him a pariah. There is no medical cure for leprosy. But Heinrich learns that the lifeblood of a virgin, who must willingly sacrifice herself to save him, can save him. Amazingly, Heinrich finds such a virgin. But when he sees her naked body about to be sacrificed on the cutting table, he decides he cannot go through with it. The virgin scolds him for his cowardice in not letting her be sacrificed. Finally, in a random act of grace, Heinrich is cured and the two live happily ever after.

Clearly this story is playing around with the contradictions of love, sacrifice, and grace. Heinrich, at first, wants to save his own skin. He must find someone who loves him selflessly in order to do so. But in encountering selfless love, Heinrich becomes ashamed and is made willing to accept his leprosy and to die of it. This is what saves him. The virgin, by contrast, is only too willing to throw herself away in order to remain undefiled by the world and to give her life to a higher purpose. She is denied in this and finds herself, ultimately, united with Heinrich in a worldly marriage in which she must lose her virginal purity. By fully accepting her humanity, she is also saved.

It is important to point out that the story of Poor Heinrich does not have a straightforward lesson. The story does not explain itself, nor does it attempt to explain the world. The feeling we get from hearing or telling the story of Poor Heinrich is that there is something tremendously important and tremendously difficult at stake in surrendering ourselves to another human being. This surrender has the capacity both to destroy us and to redeem us. We hate to be compelled to surrender any aspect of ourselves to other people. And yet, we suffer terribly when we refuse to open up the boundaries of our selves to the impact of other selves. In acts of surrender we often are brought to the realization that we neither control nor fully understand the boundaries of the self anyway. This realization is both terrifying and liberating. It cannot be faced. It must be faced.

The core dilemmas of selfhood and love from the Poor Heinrich story are preserved and refashioned in the story of the princess and the frog. That is what stories do: They morph and change as they are told and retold over the ages. That is how stories can be both ancient and still living. Within the few short pages of “The Frog Prince” are a thousand years, at least, of collective experience with the problems of love and marriage. There is a specific language and history that goes from the High German epic poetry of the Middle Ages up to the folktales that could still be heard in the marketplaces and taverns Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm visited in their own day.

The Brothers Grimm shared a fascination for stories that are dark and sometimes incomprehensible in their surface details. Such stories go deep into the heart of human experience. The stories that can never be fully unraveled, that demand to be told again and again in different variants, are the stories that are most alive. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm believed that Germans of the 19th century were losing their stories and storytellers because of war, political disruption, and the emerging forces that, as the 19th century progressed, would become modern industrial life. The Brothers Grimm believed that this was a bad thing. They believed that the very core of the storytelling art was the ability to share experience. They published their fairytales in order to keep that art alive. That’s to say, they believed that human beings are and have always been a storytelling kind of creature. • September 9, 2013