September 15, 2009. The day publishing died. Or was saved. It’s really

hard to tell which, but everyone agrees on one thing: That Dan Brown

cat sure did something major to the book industry with the release of

his new novel The Lost Symbol.

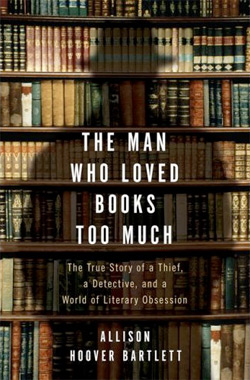

- The Man Who Loved Books Too Much: The True Story of a Thief, a Detective, and a World of Literary Obsession by Allison Hoover Bartlett. 288 pages. Riverhead. $24.95.

Outside the talk about whether the monstrous sales (one million copies sold in the first 24 hours — a record for adult hardcover fiction) will save reading, or destroy independent bookstores through the competitive discounts of their rivals, one thing is for sure: People are going to overreact to the fact that Amazon is reporting more e-book sales and than sales of physical copies of The Lost Symbol. Get ready for the latest round of books-as-physical-objects-are-dead, and the ebook will destroy publishing. (You think I’m exaggerating, but just go ahead and Google “will destroy publishing” or “will destroy reading” and see what you get.)

Putting aside the fact that there are many more advantages to reading The Lost Symbol in particular on an e-book device — no need to look at that ugly cover art, nor to be sneered at by the high and mighty book critics who might be on your subway — this is not a sign that reading is dead, nor that the book as a physical object will disappear within our lifetime. While people are going to be reading in multiple formats — including e-book readers and iPhones, Web sites and miniformats like Twitter — the book is still a fetish object.

People line up at book fairs and at places like the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, just to catch a glimpse at a first edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses, or an original Gutenberg Bible, or even a book they loved in childhood. That’s where most book collectors get their start, actually. Aleph-Bet Books owner Marc Younger specializes in children’s books, explaining in Allison Hoover Bartlett’s The Man Who Loved Books Too Much: The True Story of a Thief, a Detective, and a World of Literary Obsession, “People have an emotional attachment to books they remember reading as children… many [collectors] spend a lifetime collecting their favorite childhood stories.” Which is why a first edition of Beatrix Potter’s self-published The Tale of Peter Rabbit will set you back six figures, and an original Pinocchio in Italian runs about $80,000. As long as there are parents readings books to their children before bed, there will be adults drawn to books not just for their stories, but for their smell, their presence on shelves, the memories of the time and place they were first read, and the artwork on the cover.

Bartlett was drawn into the world of book collecting after hearing the story of John Charles Gilkey, who would eventually go to jail for stealing hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of rare books from bookstores across America. Gilkey started with an edition of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, which he bought with his own money after being assured it was a classic. His attraction wasn’t to the book itself — he reports he didn’t even like the book when he tried to read it, saying it was perverted — but to the status it implied. In owning it, Gilkey felt he presented himself as a learned man, one who could afford such a book. He became addicted to that feeling of status and started to crave a library full of beautiful, rare, important books.

Gilkey is certainly not alone in his feelings about books. Just because he acquired his collection through deceit and credit card fraud doesn’t mean his obsession with what these books represent — rather than what is contained between his covers — is somehow unique. Collector Peter Stern, who is also a rare book dealer, talks to Barlett about books he comes across that he decides he has to buy: “I ache to buy it. I want it desperately… The moment I own it, even if it’s just for a few seconds, that’s enough. I could sell it the next minute, and I don’t even remember it sometimes. I’m looking forward to the next book.” He’s also not alone in not reading the books he buys. Of course, a $2,500 edition of The Mayor of Casterbridge is not something you want to drag into the tub with you, but so few of the professional collectors and dealers talked about the stories themselves. A few did, mostly those specializing in their own very specific areas of interest (books about “outsiders,” for example, or lesbian fiction). Each is more like the person who buys the Monet at auction and immediately puts it into temperature-controlled, protective storage than anyone you’d recognize as a passionate reader.

Whatever their motivation, however, book collectors help to preserve this physical culture and ensure that our printed matter will still exist in the future. They are the most likely to fight libraries for the preservation of old newspapers or dig around estate sales and attics to find lost manuscripts by writers like Poe or Blake. Book thieves, on the other hand, not only destroy our cultural artifacts, but also hinder an understanding of our history. Most book thieves are misunderstood by the criminal justice system as petty criminals, and they are let go with slaps on the wrist. Gilkey was one such criminal until members of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America banded together under the watch of Ken Sanders and assisted in sting operations and helped document his crimes. The ABAA continues to fight for longer sentences and heftier fines, as many of these book thieves are repeat offenders. Hopefully more judges will follow the lead of the one presiding over the trial of Daniel Spiegelman, subject of Travis McDade’s 2006 The Book Thief, whose bounty totaled $1.8 million in rare books and documents, including a 13th-century Euclidean geometry textbook. In her decision, the judge stated, “This crime was quite different from the theft of cash equal to the appraised value of the materials stolen, because it deprived not only Columbia [University], but the world, of irreplaceable pieces of the past and the benefits of future scholarship.”

Reading Bartlett’s descriptions of book collections and the attachments people have to them was particularly bittersweet for me. When I made the decision to move overseas, I also made the decision to get rid of my entire library — 1,500 books. Most were sold to a used bookstore, some donated to charity, others handed off to friends. Down to several hundred near the moving date, the gentleman who came over to pick up the shelves I was selling asked what I was doing with the giant stacks now lined up around my bare walls. “Do you want them?” I asked. He immediately picked up a stack and started loading up his car. My friend Charles and I sat gloomily as the man made trip after trip up and down my stairs. I skipped refilling my glass with vodka and just started drinking out of the bottle. “It’s the stories they contain, not the books themselves, right?” I asked Charles. “Sure, kid. Can you top me off?” Some of my friends made jokes about my suddenly understanding the purpose of the Kindle, but I know it’s not the same. I don’t miss the stories in Isak Dinesen’s Seven Gothic Tales. I can hop over to East of Eden bookstore and probably find a copy of the same book. But it wouldn’t have the same smell, it wouldn’t be a perfect 1960s Modern Library hardback edition, and it wouldn’t have my 2007 Dublin bus schedule jammed between the pages as a bookmark. I don’t miss the book, I miss the book. I hope it’s being read and loved right now, and my bus schedule replaced with a subway pass or a receipt for coffee and an almond croissant. • 23 September 2009