I can’t figure out where to get a lump of coal in September. In Los Angeles. In 2013. Not activated charcoal, which is sometimes used by present-day hospitals to help suck up ingested poison. But a plain ole’ lump of dirty coal, like you would use in the 1800s to fuel your stove and give your home that lovely soot smell. This is a problem, because according to a woman with too many names — Lady Mary Anne Boode Cust — in her 1853 title The Invalid’s Own Book, boiling a walnut-sized lump of coal in an pint of milk until it gets thick is “a very nutrative food, and easily obtained.”

Well, at least for me, that second part is a lie. And sweet jeebus — coal milk? As if it didn’t already suck to get sick in the 1800s and early 1900s. It was bad enough that illnesses that maybe keep us out of work for a few days now were the leading causes of death — in 1900, you were more likely to die from influenza, pneumonia, or gastrointestinal infections than heart disease. Drinking coal milk on top of that… well, that’s adding insult to infection.

It can be difficult to imagine today how different being ill was back then. Even though there were a lot of great leaps being made in medicine in the mid-1800s through the early 1900s, there was still so much that people didn’t know. Hell, the virulent 1918 flu killed upwards of 5% of the world’s population. For context — right now, the United States has less than 5% of the world’s population. (Stephen King, please feel free to use these statistics if you want to update The Stand.)

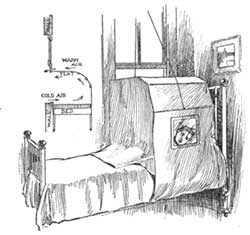

Where the sick were cared for was also much different. Bridget Collins, a graduate student in the University of Wisconsin’s History of Science department, points out that “It wasn’t until 1938 that even over 50% of American women even went to a hospital to give birth, [and]… 90% of tuberculosis patients were cared for at home by family members.” Sometimes patients were even legally required to stay home. Says Collins, “a doctor might report a case of scarlet fever, the public health department would attached a quarantine sign to the door of the house, and the patient would have to stay home for four weeks.”

Basically, getting sick was a much more worrisome event than it is today, and that’s reflected in the books about home care — and most cookbooks — from the time period (having a sick person at home was so common that most general interest cookbooks had a section just for invalid recipes). These books recommend a level of delicacy in caring for the ill that, in modern times, is reserved for handling nuclear warheads or political discussions with your extended family. In 1876’s Suggestions for the Sickroom, the author (who is simply credited as “An American Woman”) lists several guidelines for caregivers when they’re in the sick room, and it reads more like a guide for teenage girls hiding out in a horror movie:

Do not wear a starched garment or anything that rustles. Avoid all little noises — the sudden shutting of a door, the creaking of shoes, etc. Sometimes the rocking of a chair, or sewing, and passing the needle in and out of work, or turning over the pages of a book or newspaper, makes the difference between comfort and misery to a sick person.

In a spectacular use of a passive-aggressive double negative, An American Woman goes on to say, “Death is not infrequently the result of a want of watchfulness on the part of the nurse.” But no pressure, nurse-bro.

Food received a similar fearful treatment in these home-care guides. Suggestions for the Sickroom also warns, “Never let the sick person see, smell, or hear about the food before it is brought to him.” Of course, any person who has been sick knows how unappetizing food can be when you’re ill. But I can’t help but think some popular sick foods from the time did not help. For example, one recipe that shows up again and again is for some variety or another of wet toast. 1907’s Century Book of Health calls it “Watered Toast.” You toast bread, then cover it in boiling water. Or perhaps even worse, in 1901’s Invalid Recipes, there’s “Toast Water.” It sounds the same, but it’s worse — that requires you to put the toast in a jug of boiling water, wait until it’s cold, and drink that.

And toast water is a dream compared to some recipes that are unappetizing to modern tastes whether you’re sick or well. The Invalid’s Own Book (of coal milk fame), for example, also recommends tripe, eel broth, and pretty much every type of animal foot and hoof as appetizing sick food. Hey — nothing clears up the flu like a jiggling bowl of calf’s hoof pudding, right?

What might be more surprising than what is contained in these recipes books is what is not — chicken soup. Oh, sure, there are soups and chicken broths, but the ubiquitous cure-all didn’t have the hold in the late 1800s that it does, today. Instead, there was a different savory, brothy winner — beef tea.

Beef. Tea.

A late 1800s cookbook without a beef tea recipe is like an easy listening station without Kenny G — it doesn’t exist. In fact, several cookbooks have multiple beef tea recipes. Suggestions for the Sick Room has seven — plus three more recipes for beef juice. The most common method for making beef tea calls for letting raw beef soak in a jar of water. Then you put the jar in a saucepan of water and slowly heat it. Filter it, and make sure all the fat has been skimmed out. Serve that beefy broth hot.

Like anything that’s popular, beef tea had its critics. As early as 1865, people were rallying against the stuff as a wasteful beverage that provided little sustenance. A letter in the Pall Mall Gazette from July of that year notes the following (for context, LIEBIG was, unsurprisingly, a meat extract manufacturer):

The waste of beef in making beef tea is enormous. 62,000 lbs. a year are used in one London hospital alone… At the present price of meat this is a very serious matter. It is LIEBIG’s theory that in beef tea, properly made, you get all the nutrive part of the beef, and leave nothing but a worthless mass of bouilli behind. The British Medical Journal, on the other hand, asserts that fibrine is absolutely insoluble in water, and that a dog fed on beef tea dies as soon as one who gets nothing but mere water.

While we can recognize today that clearly a human (or dog) cannot survive on beef tea alone (there isn’t a paleo-broth diet yet, right?), when writing about beef tea for Epicurious, food writer Brian Yarvin notes that the tea “goes back in time to the days when the British were trying to find the essence of what gave beef its nutritional value. Since this was before vitamins and protein were known, they weren’t sure what they were looking for.” This is echoed by Collins, who says “‘Nutrients’ is not really something that comes to be popular until the field of Home Economics starts and takes up the study of vitamins (not until at least the 1910s and 20s).”

But for centuries, food for the sick wasn’t about knowing scientifically how a food helped you battle illness — it was just about knowing what made you feel better. And even if beef tea isn’t nutritionally the strongest offering, it is amazing. When I was doing the initial research for this article, I told everyone about how popular beef tea used to be, and we all shared a laugh about how gross it sounded. But beef tea is like hot hamburger water, and I mean that in the best way. It’s a warm, savory-umami bursting drink. Yes, it is wasteful: To get a cup of the stuff, I used a half-pound of beef. But it was so delicious and comforting. I could not stop drinking it. I’d put it down on the counter, and then suddenly find myself lifting up the glass again. It was like Groundhog Day — except instead of living the same day over and over, I was surprised to drink the same beverage over and over (but, unfortunately, I didn’t get to woo Andie MacDowell).

The beef tea was representative of many of the recipes I tried for this article — whether they are nutritionally the best things for you or not, many of them are tasty and comforting whether you’re sick or healthy. Does the tamarind-raisin “fever water” actually help bring down a fever? Maybe not. But it’s sweet, tangy, and delicious; and a shame that it has fallen out of favor.

So raise a mug of steaming beef tea. It’ll be delicious, and we can toast to not having consumption. • 5 July 2013

| A Quick Way to Make Beef Tea |

Suggestions for the Sickroom, 1876 Suggestions for the Sickroom, 1876

Half pound beef cut into dice, in ½ pint cold water and pinch of salt gradually heated to boiling point, and boiled ten minutes. Strain, skim, season, and serve hot. |

| Fever Water |

The Invalid’s Own Book, 1853 The Invalid’s Own Book, 1853

I loved drinking this as one part fever water, one part seltzer. For the tamarind, I used two tablespoon-sized chunks cut off one of those tamarind blocks you can find at Asian markets. “Some hours” is not a helpful measurement of time; I simmered mine for three.

|

| Bread-Crumb Pudding |

Domestic Economy, 1884 Domestic Economy, 1884 Screw toast water. If you want to eat moistened bread when you’re sick, bread pudding is the way to go. There are three things I love about this recipe: 1) You don’t need to have stale bread on hand, 2) It makes a single serving, and 3) It’s easily adapted to be sweet or savory. I baked mine in a ramekin at 350 F until a knife stuck inside came out clean, and I served it with a bit of currant jam on top.

|

| Stewed Prunes |

The Century Book of Health, 1907 The Century Book of Health, 1907

If you’re the sort of person who thinks about poop when you think about prunes and immediately discounts the fruit — just stop. Prunes are delicious. Try adding a bit of orange peel and cinnamon stick to this recipe as it simmers.

|