One year ago, Berlin’s Martin-Gropius-Bau museum and New York’s Museum of Modern Art staged a massive exhibition of the Bauhaus school of Weimar, Germany. Bauhaus was rooted in daily life, the fusion of high and applied arts. The exhibition was arranged much like the school itself — playfully and with much experimentation. It may have opened with Johannes Itten’s stunning “The Fire Tower” sculpture, but it also explored the education process that brought things such as “The Fire Tower” to life, the building blocks of art and the often messy learning process.

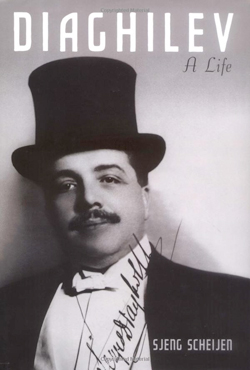

- Diaghilev: A Life by Sjeng Scheijen. 560 pages. Oxford University Press. $39.95.

The walls of one room were hung with variations on a homework assignment. The art students were asked to take a photograph from a newspaper and relay the information of the piece through artistic representation. One wall was dedicated to color wheels, another to experiments with typography. There were failures here, too, which so infrequently get space in a museum: wonky self-portraits, attempts with photographic effects that had mixed success. In video interviews, instructors and students spoke with that starry-eyed idealism that can still exist in school, before you discover that the “real world” includes things like Nazis: they wanted to change the world with their art. (Whether or not you think they succeeded probably can be determined by whether or not you think Mies van der Rohe ruined perfectly nice parts of Chicago with his buildings.)

The exhibition was a reminder that not all art schools fit the stereotype of assembly lines producing mediocre careerists. Writers are currently mired in a raging debate as to whether schools, specifically MFA graduate degree programs, are destroying American literature. (Well, the debate has been on a low simmer for decades now, it seems, but occasionally someone will spill it over onto a burner and fill the room with smoke. This time it was Elif Batuman with her London Review of Books essay “Get a Real Degree.”) MFA programs are churning out thousands of degreed writers every year, and never has American writing seemed so mediocre, so homogeneous, so very, very dull.

The Bauhaus school helped artists build the skeleton of their future work. Students learned color, typography, and blueprints; instructors showed them how to bring that education to various mediums, from photography to weaving to toy-making to architecture. The result is, well, Bauhaus — that identifiable thing when you look at a piece and recognize the structure for what it is. Despite the way the skeleton has been fleshed out, or what clothing it’s draped in, your brain can still see and respond to the Bauhaus-ness of it.

Whether or not that kind of training is useful to the writer is at the core of the debate. The schools of learning don’t really produce schools of writing, after all. There’s not anything distinctive and recognizable as being from “The Iowa School.” And Iowa, or really any of the MFA programs, have not produced genius. They have produced some fine books, some solid writers, nice introspective novels about dramatic comings-of-age, and multi-generational rags-to-riches sagas. And maybe genius doesn’t need to go to school. Maybe genius already knows what it’s doing, and its skeleton is pre-built, with tentacles instead of arms, or with a third eye socket in the middle of its forehead. Maybe genius already has its own reading list.

But even Picasso had to do life study drawings. Bauhaus may have produced a lot of graceless, squat buildings, but it also gave the world Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe. When the final arguments for the MFA are made, it usually comes down to “community” and “space.” Spending a few years in the company of other aspiring writers with the time and encouragement to write, defenders argue, is worth the tens of thousands of dollars of debt, even if the degrees don’t give you anything else. But the criticisms of the MFA program — that they turn out mediocre novels written by committee, that they cut writers off from experimentation, that they promote introspection at an age when young writers should be exploring the world — have remained consistent through the years.

The complaints made of writing programs are the same consistently used against art school, or music conservatories, or, hell, primary schools, wherein we all march, The Wall-like, to be turned into brainless automatons. It’s not as if Bauhaus found a miracle formula and since then, art schools have copied it and spat out genius after genius. And Bauhaus was not a magical place that allowed you to be all you can be. If you were a woman with aspirations to be an architect in the Bauhaus era, you were actively discouraged, as the instructors believed women can’t work with three-dimensions.

When I imagine the ideal education for an artist — whether he be a writer, a composer, a dancer, a painter — it is something like the childhood of Sergey Diaghilev, as described by Sjeng Scheijen in his new biography. Diaghilev not only grew up wealthy and, for a time, as part of St. Petersburg’s high society: He was also raised by art lovers. Music filled his house; his father brought in musicians and composers to perform operas in the living room. Tchaikovsky was a family friend. As a student, Diaghilev corresponded with Leo Tolstoy. When he became obsessed with Wagner (as one does), he was able to go to Bayreuth for a season to gorge on its offerings. The correspondence between Diaghilev and his stepmother include long discussions about literature and philosophy.

Any artist would envy the from-birth education. Diaghilev, however, never became much of an artist, despite composing a few things as a young man. He discovered his limitations rather quickly, but luckily knew full well his strengths, as he wrote to his stepmother, “First of all, I am a great charlatan, although one with flair; second I’m a great charmer; third I’ve great nerve; fourth I’m a man with a great deal of logic and few principles; and fifth, I think I lack talent; but if you like, I think I’ve found my real calling — patronage of the arts. Everything has been given me but money.” He did have talent, but it wasn’t as patron — it was as trickster, as deviant, as producer, as alchemist. He created the Ballet Russes and made his company the most vital group of artists, musicians, dancers, and writers in the entire world, at a time when ballet was mostly a joke — a social outing for old ladies.

Diaghilev’s upbringing may have failed to make an artist out of him, but it did make him an incredible teacher. He was able to recognize genius in undisciplined talent and to create from scratch in others. The immense talent he was able to nurture and mold is incredible. His lover Nijinsky started as a young and powerful but middling dancer before becoming the high point of 20th-century dance, as well as a revolutionary choreographer. Composers such as Prokofiev and Stravinsky created some of their best work for Diaghilev, particularly Stravinsky’s Petrushka and The Rite of Spring. Leon Bakst became legendary for his work with the Ballet Russes. Picasso, Matisse, Balanchine, Anna Pavlova, Coco Chanel, Natalia Goncharova all longed to work with Diaghilev, despite his perpetual financial insolvency. He brought some of their best work out of them, convincing some to work in mediums unfamiliar and uncomfortable for them, and introducing others to pivotal collaborators.

When Diaghilev wanted to turn Massine, his latest protege, from a dancer into a brilliant choreographer, he took him to Italy to look at paintings and sculpture. Massine was skeptical, as was the rest of the world, that he possessed any genius. But there, after a tour of what European artists can do with devotion, discipline, and skill, Massine was inspired. Massine wrote, “As I looked at the delicate postures of Gabriel and the Virgin Mary, I felt as if everything I had seen in Florence had finally culminated in this painting. It seemed to be offering me the key to an uknown world, beckoning me along a path which I knew I must follow to the end. ‘Yes,’ I said to Diaghilev, ‘I think I can create a ballet. Not only one, but a hundred, I promise you.’” Massine may not have choreographed a hundred ballets for Ballet Russes, but his contributions were significant.

Scrawled on a display case of the Bauhaus exhibit were the words of one of the instructors: “Trial is better than study, and a playful beginning develops courage… In the beginning, the material alone is important, if possible without tools.” If education alone could create genius, Diaghilev would have been a greater composer than Stravinsky, and America would be producing the greatest literature the world has ever known. But the creators of Bauhaus and the Ballet Russes prove there is something about an environment of creative collision, knowledge, and building up from a foundation that can foster greatness. Can art be taught? Yes, of course. Not every instructor will be a Diaghilev, and not every student will be a Nijinsky. But if the MFA programs are not able to produce, or are not attractive to, geniuses, there is something to be learned from the playful experimentation and the exuberant enthusiasm of the schools that are. • 6 October 2010