At the close of the 20th century, I found myself wandering the streets of Ulaan Bataar, Mongolia in reluctant search of someone willing to talk about Chinggis Khan. It was an assignment for my study abroad program, and I didn’t want to do it. I had just barely skimmed the assigned excerpts of The Secret History of the Mongols, the story of the rise of the Mongol Empire, and for the two weeks since we were given the assignment, I hadn’t bothered to approach a single person.

A couple days before the write-up was due, I hung out in Sukhe Bator square and tried to work up the courage to talk to people, but everyone looked so respectably private. Many were walking to destinations in cashmere sweaters and suit jackets, jeans, riding boots, and felt caps; others walked away from me in traditional nomadic dress and boots. It was fall and I was happy when the wind picked up because then I could allow myself, with good reason, to give up on the assignment.

So I stepped inside the natural history museum that was just off the square. I was the only visitor. In one room there was nothing between me and two big, fighting dinosaur skeletons but a single string. On the way out, I tried to talk to the ticket taker about Chinggis Khan, but she would have none of it.

I walked back to the apartment our program had paid a family to vacate for the month and watched some fashion shows on the absent family’s TV. Models like hollow-boned, wingless pterodactyls marched toward us in an endless techno parade. My roommate Chris and I watched and ate Russian digestive biscuits for dinner while another roommate read and highlighted The Secret History from her bed in the family’s living room.

“Can you turn that down?” she asked.

“Can’t you go to another room?” I countered, and I was almost sorry to leave the room when my kettles of bath water came to a boil on the stove.

In the bath I stared at the family’s ceiling and wondered who they were and where they went. The techno thumped through the wall. When I came back into the living room, I was glad Chris was still watching fashion TV, and the models were still marching toward nowhere with authority. “Dude, those girls are hurt,” he said.

“Hurt” was Chris’ favorite phrase. He used it to describe restaurants, poorly translated lectures, and one student who came close but didn’t make it up to the eighth floor of our Soviet-style walk-up before puking an ice cream cone in the stairwell. According to Chris, “hurtness” was everywhere, and it was hard, after a few astute observations, to argue with him.

When I showed up at the Internet café near the state department store the next day, I saw Chris talking to a Mongolian man who was red-faced and drunk. I knew where the conversation was going because Chris hadn’t done his assignment yet either. I pulled a chair close enough to see the broken capillaries in the man’s face, maybe from alcohol or maybe from a nomadic, wind-burned childhood. At any rate, it gave him a rosy look that, along with his fedora and suit jacket, made him look like he came from the beginning of the 20th century. As he described his life as an out-of-work engineer for a Russian coal mining company, he periodically stopped to yell or yell back at his girlfriend, who was also drunk and sitting in the corner at a separate table.

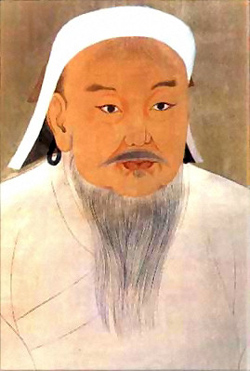

Chris asked if the man knew Chinggis Khan, and the man started to talk in the present tense about Chinggis, who has been dead for 800 years. He said, “I love Chinggis.” I looked at Chris and wondered if we were going to get what we needed from this interview. Chris asked him some leading questions with references from our readings. I mimed a compound bow. I attempted to draw a mare’s teats and an eagle. I sketched a map of a territory that stretched from the Yellow Sea to the rim of Europe, and then I added arrows originating in Mongolia and bound for the rest of the world.

The man agreed with everything we said and he seemed to have a pretty good vocabulary, but he just wanted to repeat himself like a drunk at a wake. He put his head in his hands, like Chinggis’ death was his own relatively recent loss, and just kept repeating, “He is so clever.”

“Was,” I whispered.

The man and his girlfriend squabbled between the tables throughout the entire interview. At first I thought he was trying to piss her off and make a scene, which he successfully did. Then I wondered if he wasn’t using Chinggis as a means of expressing some leftover anti-communist sentiment, which I think he might have been, but there was more to it. His eyes were damp. Maybe he really felt related to Chinggis Khan and missed the hordes, or maybe he missed his own family wherever they were.

We talked to the man about his dream of moving to the U.S., but he didn’t know much about what it took to get a visa. We wished him luck and thanked him before stepping out of the café, where Chris delivered his opinion in the cold: “That man was hurt.” We were young and lacked manners and empathy, and Chris’s timing was perfect.

Honestly, as we walked down Peace Avenue, it felt good to leave the man behind. He loved Chinggis and Mongolian history, but today he also wanted to escape the country and maybe consciousness itself. It was hard to listen to. When Chris announced the man was hurt it felt like a relief to hear the obvious and irrefutable announced about someone who was not me. We kept walking. I was not, for the time being according to Chris, one of the “hurt.” •