The now-defunct Gourmet magazine had an ambitious goal: tap into America’s pioneering nature and refine this adventurousness into a thirst for good living. By January 1941, the Great Depression had worn everyone down. Americans were ready for a magazine that reminded them of happier, more prosperous times. They wanted travel, adventure, luxury. Earle R. MacAusland, creator of the magazine, was banking on it.

There was no inherent reason Americans couldn’t appreciate the finer things, posed MacAusland. “The art of being a gourmet has nothing to do with age, money, fame, or country,” Gourmet stated in its first introduction. But appreciating good living is not exactly the same as living well. Americans had a land of plenty but centuries of uncouthness working against them. They would need to model their tastes after those with more experience — Europeans, namely, which really meant the French, who were considered the arbiters of global gastronomy. The cover of the magazine’s first issue said it all: a roasted boar’s head decorated like Christmas, with mistletoe in its ears. Early French and English settlers brought the tradition of Boar’s Head Christmas to America in colonial times, but it was usually prepared in churches and in the wealthiest households. To most Americans, boar’s head was evocative of Henry VIII or the Austro-Hungarian Empire or Napoleon’s court. What American in 1941 (or ever) was roasting boar’s head? But that wasn’t the point. The boar’s head wasn’t meant to show America how it was actually living, but how it could be living.

Of course, the actual Europe was a mass of genocide and war in 1941. Decadence was enjoyed by the very few (who were themselves, ironically, in the process of destroying it). By the time Gourmet’s first issue hit the stands, France had been occupied by Germany for about eight months. Among the indignities French people faced were major food shortages and rationing. Sugar and coffee were near impossible to get, never mind a boar’s head. In the cities of France especially, hunger was common. One year later, in December 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and the United States was lured into the war it had hitherto avoided. The American audience of Gourmet’s second year were to face the same food shortages and rationing. “Take thine ease, eat, drink, and be merry” — quoted in Gourmet’s first issue — wasn’t exactly well-timed sentiment.

But Gourmet thrived for nearly 70 years, becoming America’s most venerated food and wine publication. It succeeded not because Americans finally learned to make the boar’s head of their dreams. And not because Gourmet tapped into a nostalgia for pleasures past. When you flipped through the sumptuous illustrations of faraway hotels and French recipes half-written in French, it didn’t matter that they were recipes you would never understand (much less cook), hotels you would never visit. Gourmet succeeded because it offered a fantasy. A fantasy of a sophisticated, civilized pre-war Europe.

In its last issue, Gourmet gives a nod to what it calls the “great American food Revolution of the past 10 years.” More than ever before, the world of good eating lies before Americans, and they are taking advantage of it. But the word “revolution” is misleading. The change didn’t just happen over the past 10 years. Americans have slowly been revolutionizing their palates since the 1950s, due in part to Gourmet. I know I’m not the only American who remembers when grocery store cheese was of only two varieties — yellow and pre-sliced. When only Japanese people ate sushi. Falafel? Hummus? Pad Thai? These have all solidly joined the American culinary lexicon. The foods of fantasy we now take for granted are available partially because Gourmet developed in us a desire for them. This desire to eat better itself became the impetus for Americans to do so.

Yet with news of Gourmet’s demise, we are reminded that desire is not enough to carry on a revolution. The New York Times this week complained that we are now living in the world of Rachael Ray — in other words, a world of 30-minute E-Z meals that lack discernment, soul. But critics of Gourmet say the magazine is folding because it has little to offer the 21st-century American who cares more about getting food on the table than decadence. “Cooking is getting more democratic,” said Suzanne M. Grimes of Every Day with Rachael Ray in the Times article. “Food has become an emotional currency, not an aspiration.” They are both right. Cooking is perhaps more exciting than ever to Americans precisely because of its democritization. Democracy needn’t be seen as the dumbing-down of American tastes. Today, most of what Rachael Ray cooks is a million times more “sophisticated” than it would have been even 10 years ago because of cultural influences like Gourmet. The real leader of the revolution, however, was M.F.K. Fisher.

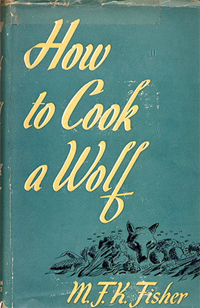

In 1942 the celebrated writer was heartbroken by the sparse offerings of wartime rationing. Ten years earlier, Fisher had her own culinary love affair in France. She returned to America wanting — like the editors at Gourmet — to inspire in its citizens a similar passionate relationship with great food. Rather than offering her readers a fantasy, though, she responded to the times with How to Cook a Wolf. The book synthesized reality and joie de vivre by encouraging an appreciation of daily living. The chapters were at once practical and joyous: “How to Greet the Spring,” “How Not to Boil an Egg,” “How to Be Content with a Vegetable Love,” “How to Be Cheerful Through Starving.” It excoriated the (unnamed) magazines that “set up a fantastic ideal in the minds of family cooks” and instead promoted this: “Now, of all times in our history, we should be using our minds as well as our hearts in order to survive…to live gracefully if we live at all.” Even though written in wartime, the sentiment is the heart of Fisherian ethos, which looks more contemporary and relevant than ever.

|

Fisher’s oeuvre fills the gap between traditional European sophistication and American heartiness. She created a signature brand of unpretentious decadence, a decadence that turns simplicity into luxury just by exploring it. (It was the complement to the project of contemporary Julia Child, who made luxury more accessible by simplifying it.) Let’s call it “nouveau decadence.” Fisher passed this attitude on to every facet of American culinary culture, including Gourmet magazine, which ironically would become one of Fisher’s greatest proponents.

Gourmet eventually allowed for more Fisherian simplicity and accessibility in its pages. The last issue is a case in point, particularly its “Gourmet Everyday” fare such as 20-minute Portobello Buffalo Burgers, 15-minute Peppery Pasta Carbonara with Poached Egg, and Italian Vegetable Stew. The problem is that “Gourmet Everyday” isn’t far in spirit (or ingredients) from, say, the vegetarian dishes on Rachael Ray’s Web site (Portobello Burgers with Roasted Pepper Paste and Smoked Mozzarella, Three Vegetable Penne with Tarragon-Basil Pesto, Vegetable Stew with Potato and Cheese Pancakes).

The Rachael Rays and Gourmets of the world are both soldiers in Fisher’s army. They are both championing an American cuisine that is international rather than worldly, adventurous rather than unattainable. A cuisine that’s imaginative, personal, and democratic. It’s just that, today, the Rachael Rays speak more to the masses than Gourmet and that is necessary for a revolution to succeed. It may be cold comfort, but champions of Gourmet should be heartened by what the magazine gave to Rachael Ray fans. An appreciation of the finer things. Albeit in 30 minutes or less. • 8 October 2009