I came to the current religion debates a bored man. Started by the

discussions around “intelligent design” and by the books of Dawkins,

Hitchens, Dennett, and Harris (The Four Horsemen), the debate seemed to

pit two irreconcilable views against one another, both vying for an

empty prize. Religion, I gathered, will always have its place, as will

the practices of science and rational inquiry. Perhaps one day some

other arrangement, some other separation of powers, will come about,

but it won’t be any time soon, and it will happen when no one is

looking. It will happen on its own time, with the lazy mastodon

movements of history, which lumbers and rarely sprints.

It has also often struck me in some inchoate way that while the

basic tenets and practices of any specific religion aren’t terribly

impressive, the intellectual dilemma of faith and faithlessness has

something to it. Sure, religion has its ugly side and must strike

everyone in at least one moment of clarity as being something close to

crazy. But, then again, the cleverest of the religious thinkers have

always admitted this, have even tried to turn it into a strength. It is

hard, for instance, not to admire the way that Tertullian, the

Carthaginian Christian philosopher of the second century, stood up to

the fundamental absurdity of his faith and proclaimed “credo quia

absurdum,” “I believe because it is absurd.” Not I believe even though it is absurd, but I believe because

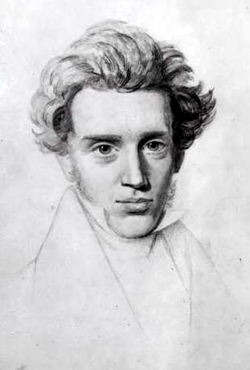

it is absurd. In a more modern variant, the tortured mental gymnastics

that Kierkegaard goes through in his defense of the story of Abraham

and Isaac goes beyond simplistic apologetics. For Kierkegaard, the

story is powerful because it makes no

sense from any reasonable perspective; it is utterly unthinkable that God would tell Abraham to

sacrifice his son and then wait to see if he’d actually go through with

it. The story is so terrible that it demands attention, and in

demanding of us it gives us access to something more powerful and more

true than what is generally encountered in the world of practical

necessity and contingent decisions that we live in the rest of the

time. It forces a decision.

Indeed, Kierkegaard may be suggesting something profound here, which is that the struggle over belief, the struggle

of faith is more fundamental than the actual possession of it. This is

a more subtle point than that made by the religious dogmatists. It

doesn’t say that religion is fundamental as a set of principles. It

says that the problems of religion are fundamental. In this view, faith

and doubt are intertwined all the way through. More strongly, doubt is

seen to be contingent upon, to be meaningful only alongside, its

antipode faith. For Kierkegaardians, you don’t have doubt without faith

and vice versa. The most powerful, the most meaningful accomplishments

that have emerged from the human swarm, are the result of that

provocative tension, doubt pushing and sliding into faith and then

faith leaping suddenly out of a sea of doubt only to fall again, as all

things do.

This is something that the excellent critic at the New York Sun, Adam Kirsch, touched on in his review of Daniel Dennett’s book Breaking the Spell.

Dennett means to initiate a scientific research project whereby

religion will ultimately be exposed as a product of human biological

history whose relevance to the contemporary situation of human beings

is at least highly questionable. Kirsch thinks that Dennett, in his

scientific project of showing the historical origins of religion and

its biological foundation, has fallen into the “genealogical” fallacy

in which you make the illegitimate move of going from describing

something to judging it. And Kirsch is certainly correct that Dennett

is entirely tone deaf to the way that religion plays an important role

not insofar as it is something to believe or not to believe, but in the

sense that the drama of doubt and faith has informed many of the

central works of Western philosophy, literature, and art. For Kirsch,

even if we can explain the emergence of religious belief from a

scientific standpoint that doesn’t abolish its significance for actual

human beings. He writes:

Mr. Dennett believes that explaining religion in evolutionary terms

will make it less real; that is the whole purpose of his book. But this

is like saying that because water is made of two parts hydrogen and one

part oxygen, it is not really wet; or because the color red represents

a certain frequency of light, it is not really red. To human beings,

the wetness of water, the redness of red, is existentially prior to

their physical composition. Just so, the reality of religious

experience cannot be abolished by explaining it as an adaptation to our

prehistorical environment.

I don’t know if Kirsch is right about this or not. But I don’t think

he knows either. It’s a smart point; it moves me. But there is

something slippery in the analogy. The wetness of water or the redness

of red are not abolished by our knowledge of their physical

composition, partly because there isn’t anything contradictory about

experiencing water as wet and knowing that it is composed of two parts

hydrogen and one part oxygen. It may be weird and beyond explanation

that water “feels” wet, and there is a long debate amongst the

philosophers about the nature of such “qualia,” i.e., the nature of raw

experiences like wetness and redness. But there is still nothing about knowing that water is composed of hydrogen and oxygen

that makes me want to deny that it feels wet to me, or to somehow

prevent it from feeling wet to me now that I know it is just a bunch of atoms. Indeed, I can even go so far as to accept that wetness is simply

the feeling we get, the way we are affected as human beings when two

particular elements combine to form a compound. Again, even if there

is something mysterious going on there, it is a mystery that doesn’t

necessarily play as a contradiction. Feelings are one thing, chemistry

another.

Knowledge and beliefs, however, are much more closely related. What

I know has direct bearing on what I believe. There is a “because”

involved there, even if it is in the seeming absurdity of Tertullian’s

“I believe because it is absurd” or in Kierkegaard’s leap into faith.

You don’t experience water as wet “because” of anything; it simply

happens. No matter how much knowledge you acquire about molecules and

atomic structure you cannot decide to stop feeling water as wet. The

description did not dissolve the experience. But faith is all about

decisions. It is about making choices in response to your experience of

the world. If I know, really know, that religion emerged out of the

same Darwinian processes that have created and shaped other human

practices, then it is going to be difficult for that knowledge not to

seep into my beliefs.

It may be that religious experience is so fundamentally wrapped up

with what it means to be human that no amount of scientific work will

puncture that existential core. But damn it, what if we really could

puncture it? The kind of knowledge that Dennett and Dawkins are after

in exhaustively describing religion and its basis in human evolutionary

development is, one must admit, at least potentially threatening to a

religious conception of the world. And that is what makes the new

religion debates exciting after all. There is something stirring in the

public discourse. We are talking, here, about the possibility of

opening up an entirely new era in the history of human kind. Not a

small thing. It doesn’t lessen one’s respect for how important the

dilemmas of faith have been in human history hitherto to admit that

going forward it might be otherwise. I trust that there will always be

human dilemmas, at least as long as there are humans. But it is always

thrilling to realize that things can be changed, that there is new

terrain to be explored. And as Hitchens in particular points out in his

brutal indictment of the religious mindset, there are some very good

reasons to test that new terrain and to see if we can’t just leave

behind much of the fear and intolerance that seems to go hand in hand

with the question of faith. We failed to kill God the first time. Who’s

to say what might happen the second time around? • 11 October 2007