Readers are notorious grave robbers. When it comes to our favorite

authors, many of us posses a compulsion to read and learn everything.

We cheer when manuscript fragments are uncovered, private

correspondence tracked down, diaries published for all to read. The

authors, long dead, can no longer insist on privacy, and it is often

their loved ones and descendants who betray them by leaving items

unburned and handing over love letters to publishers.

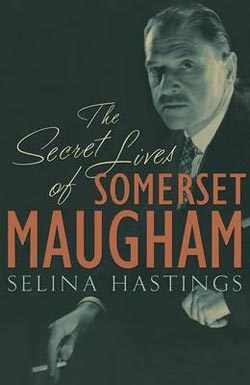

- The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham by Selina Hastings. 624 pages. John Murray. £14.99 (U.S. May 2010).

If you look at the fall publishing list or read literary news you might think the dead have come back to walk the Earth. Vladimir Nabokov’s The Original of Laura — not so much a book as a series of detailed note cards about a book — is being published after years of hemming and hawing by his son Dmitri. Vladimir had requested the note cards be destroyed, not published. Readers have been able to follow the heir’s decision making process after Ron Rosenbaum started publicly pressuring Dmitri to choose publication via Rosenbaum’s column at Slate. The Internet was allowed to chime in, as if the issue were the equivalent of a poll asking if Miley Cyrus was right to shut down her Twitter feed. We also have “new” “works” by William Styron, David Foster Wallace, Ralph Ellison, and Kurt Vonnegut all coming out this fall, as well as a controversial version of Carl Jung’s The Red Book, which had remained completed, but hidden with no specific request to publish it, for years before his family finally decided to go ahead and make it public.

There is also a current battle between the descendant of James Joyce and a woman — the daughter of the lover of a friend of Franz Kafka — who possesses diaries and letters and manuscripts and is refusing to share. People are suing for access and publication rights. Say what you will about cultural history and scholarship and the good of mankind, it does raise some uncomfortable issues about what is private property — or what is “private” at all — when you become an author. Does publication automatically entail having your entire life ripped open and examined?

W. Somerset Maugham worked hard to cover his tracks for most of his life, and for good reason. Oscar Wilde’s trial was front-page news and with it came the sudden revelation that discretion was not enough to keep homosexuals out of jail. Maugham eventually married and had a daughter, but he carried on affairs with men his entire life. Selina Hastings writes in her new biography The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham, “The trial of Oscar Wilde was to cast a long shadow, and for 70 years Maugham’s generation had to live with the very real fear of blackmail, exposure, public scandal, and arrest.” Maugham did an excellent job destroying all evidence of gay love affairs from the first half of his life, and Hastings is left to piece together tiny clues — a recurring name used for characters in Maugham’s fiction, for example, or the gender neutral pronouns in Maugham’s autobiography The Summing Up.

A fear of persecution may not have been the only thing driving Maugham’s discretion. His was a complicated love life. It’s something the devoted reader could have guessed. From Of Human Bondage‘s tale of the destructive power of sexual obsession to the murderously unhappy marriage in The Painted Veil and the self-destruction of marrying someone who does not understand you in Mrs Craddock, it’s easy to see a pattern forming.

Maugham put it best himself in The Summing Up: “Although I have been in love a good many times I have never experienced the bliss of requited love.” Hastings goes so far as to speculate which boy at Maugham’s public school could have been the one he fell for based on the number of syllables in the students’ names versus the number of syllables in the names of the love interests in his novels (really). It seems unnecessary, as the affairs the writer left evidence of are enough to provoke sympathy. When he proposed to Sue Jones, a promiscuous and lively woman who happened to be sleeping with many of Maugham’s friends, she had just discovered she was pregnant with Angus McDonnell’s child and there was to be a quicky marriage. The woman he did marry, Syrie Wellcome, was something of a needy gold digger, and there are suggestions that she either sabotaged her birth control to become pregnant by Maugham, or he was just one of several potential fathers of the child. He had started his affair with her while she was separated from her husband, but still married. When her husband discovered this, he used it as an excuse to name Maugham in a scandalous divorce, although Maugham managed to keep it quieter than it could have been. His long-term gay lovers were often placed into employment as Maugham’s secretaries, making a convenient excuse for why they must accompany him on his months-long trips around the world. He was a refined fellow who valued his ability to keep up an appearance of propriety.

That carefully constructed wall between the public and personal, however, crumbled near the end of his life. It’s hard to imagine now, but Maugham was a superstar in his day. (The usual response I’ve received when I mention reading one of his books is, “Oh, my grandmother used to read him.”) His plays were hits, his novels instant bestsellers. He was a spy in Russia for the British government during World War I. He had Winston Churchill, Virginia Woolf, and Noel Coward over for dinner. He had become rich enough from his writing to own an estate in France and a very impressive art collection. There was a large appetite for gossip about his life, and he was manipulated by his lover/secretary Alan Searle into telling his life story, despite increasing senility and anger about the men and women who had used him. The result was a scathing portrayal of his marriage to Syrie, and the public was harsh in their response. The open secret about his affairs with men became open accusations in the newspapers. The unhappy life he had disguised in fiction and played down significantly in The Summing Up was now running through the tabloids.

Searle’s motivation was, of course, pure profit. He had convinced both Maugham and his daughter that each one hated the other in order to become the sole heir. It went so far that a senile Maugham attempted to use the fact that Syrie had given birth to their daughter before they were married to disown her legally and then adopt Searle as his dependent. The courts rejected it, but Searle still walked away with almost everything. Even Robin Maugham, his nephew, started taking notes in order to reveal the secret life of this bestselling author in a biography, essentially blackmailing the author into paying him more than the publisher had offered. Maugham’s life still has the power to shock now that Hastings has revealed even more than the tabloids at the time knew: the multiple lovers skinny dipping at Maugham’s estate, the fact that Maugham took lovers significantly younger than himself, his patronage of brothels. She refers repeatedly to his voracious sexual appetite. The Daily Mail responded to the revelations in Hasting’s biography with the headline: “Is [Maugham] the most debauched man of the 20th century?” (My response: Do you even remember the 20th century?) Of course all of this would be much less shocking had he stuck to female lovers — and he did try to convince himself for a while that he was more straight than gay, and that his desire was just a minor aberration.

If there’s a lesson from this sudden dead author revival, it’s that you should immediately start burning anything you don’t want released instead of waiting for the ones who follow to start cashing in. As a longtime fan of Maugham’s work, I was certainly curious about what inspired him to write such vicious accounts of marriage. Although now that I know how incredibly unhappy he was to be forced to marry Syrie, does that add to or detract from my favorite scene in The Painted Veil in which the husband tells his wife he knew she was a frivolous idiot when he married her, and now he’s carting her off to a cholera epidemic in the hopes that one of them will die? In his review of The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham, the Guardian‘s Ian Samson referred to biographies as “reverse alchemy,” taking the gold of the creative act and turning it back into the lead of mundane daily life. Remember this next time readers cry out and demand to read a famous author’s unpublished short story, and then afterward look around embarrassed, realizing why it had been left unpublished, and wish they hadn’t read it after all. • 21 October 2009