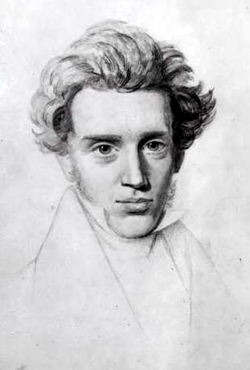

Kierkegaard was a dissembler and a clown. He had a Christ complex and a

club foot. He looked great in an overcoat with a turned-up collar. Much

of his adult life was spent mentally obsessing over a woman. Catullus

had his Lesbia. Dante had his Beatrice. Petrarch had his Laura.

Kierkegaard had his Regine. She appears in some form or another in all

of his writing. The reader can be forgiven for not recognizing Regine

as Isaac in the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac, but that’s the way

Kierkegaard saw her.

By all accounts, Kierkegaard and Regine Olsen were genuinely in love. The two were affianced in 1840. But by 1841, Kierkegaard had decided to call it off. Thus begins the great mystery of his life. Why did Kierkegaard choose pain and despair over happiness? The answer, I’m sorry to tell you, is the complete works of Søren Kierkegaard.

Still, we’ll try to tease out a few key talking points. Central to the story is faith. Some think of faith as a simple matter — you have it or you don’t. For these people, further inquiry is unnecessary. Faith is not accessible to reason. Kierkegaard agrees, a little bit. He never thought that faith could be understood through logic or rational thought. Faith, for him, had to have an element of the absurd or it wouldn’t be something special, something outside the normal rules. But he did not think of faith as simple. He saw it as the hardest thing, the greatest challenge, the center of the grand torture we call life. He once said, “If I am capable of grasping God objectively, I do not believe, but precisely because I cannot do this I must believe.”

Kierkegaard had a good sense of humor, in a 19th-century Danish sort of way. Let’s call it a dry wit. He would open up treatises with sentences like, “In my opinion, one who intends to write a book ought to consider carefully the subject about which he wishes to write.” Because he saw truth as fragmentary, he made up a number of characters from whose perspective he would often write. That allowed him to take wing in one persona or another, to follow out the particular truth in this or that perspective. There aren’t very many philosophers who you can genuinely call writers. Kierkegaard is one of them. His prose can be beautiful, which is not irrelevant to the substance of his philosophical thought. “You, my happier self, you fleeting life that lives in the stream that runs next to my father’s estate, where I lie stretched out as if I were a walking stick someone had lain on the ground, but I am saved and liberated in the melancholy murmuring! — thus I lay in my box, tossed away like the clothes of a bather, stretched out beside the stream of shouting and laughter and general abandon, that continuously rushed past me.” Kierkegaard hated philosophy in the grand style. He was no system builder. Instead, he was always after an intimate truth. Philosophy, for him, was about an individual human being grappling with exactly what it means to be alive, to make decisions, to go one way and not another. Kierkegaard wanted us to be terrified in the face of life because in doing so we might come to the uncomfortable realization that it matters very much.

To understand that fact, to understand how much we care about the world is also to understand we’re too wretched to do anything about it. In relation to God, Kierkegaard thought, “I am always in the wrong.” Life, for Kierkegaard, meant coming up against the hard edge of that understanding over and over again. But in doing so, a release becomes possible, a beautiful kind of freedom. Accepting that one is always wrong in relation to God means that each individual must simply choose to be who he or she is. This is the “leap of faith” in Kierkegaard’s thought. Because we are always wrong, we are freed up to take that plunge. “Do not,” begs Kierkegaard, “interrupt the flight of your soul; do not distress what is best in you; do not enfeeble your spirit with half wishes and half thoughts.”

I suspect that Kierkegaard broke things off with his love Regine so as not to enfeeble himself. It was a terrible choice, to choose the wrong thing for the very reason that it was wrong. But it makes sense in a cruel way. He wanted to heighten his leap, to maximize the mattering of it all. For a brief moment he got to be Abraham, willing to murder the thing he loved most.

•

Repetitions

In this work, Kierkegaard considers the difference between repeating and reliving. Reading it, I always think of the familiar bit of shampooing wisdom that instructs us to “wash, rinse, and repeat.” Here is repetition without nostalgia. No one in their right mind attempts to recreate exactly the first experience of washing and rinsing in the third, or the fifth. You just repeat. You do it again. As you do, each repetition has its own flavor. Maybe the fruity smell is of notice in the second go-round. Perhaps there is some excitement in the increased amount of suds the third time through.

These experiences are transitory, the meeting up of chance factors. The attempt to relive that exact smell, to retrieve the magic of that random sudsing would be to misunderstand the nature of experience in general. It is to want something that you cannot have. You can never experience that first shampoo in exactly the same way.

To want things we cannot have is part of being human. We’ve all tried to go home again, and failed. There’s a hedge in a small Montreal park where my parents often took me as an infant. There were swings, and a metal slide I once fell from. I will forever remember that hedge as a massive boundary, the gateway to an outside world, there beyond the alleyway that led out from our kitchen door. The journey from the alleyway to the hedge will always be the first journey for me. It took me a thousand years to run down that alleyway and finally reach the hedge and the park on the other side. I went back to see it as an adult and there it was. A tiny alleyway behind a row of houses, a midsize hedge badly in need of care.

For many of us, the disappointment inherent in trying to relive experiences transforms into a rejection of all the quirks and surprises of the real world. We flee to the ideal, whether in memory or into the projected realm of concepts. Our inner Platonist takes over, driving the horse carriage of the soul ever upward into the unsullied beyond.

But the solution, if we can call it that, was never so far away. Wash. Rinse. Repeat. The more you do it the more you settle into the rhythm of sameness and difference. There is continuity in that change. A lifetime of washing, rinsing, and repeating is a lifetime of ever-deepening experience, of finding out just what kind of repeater you are, just how you do it differently each time. You never know just how the light will hit the bubbles, whether you’ll hear the sound of someone tinkling at the piano keys rambling up the gap between the buildings and through your open window. You come to know who you are, but never exactly what you will do. That relationship with one’s own possibility is unsettling. “There is nothing with which every man is so afraid as getting to know how enormously much he is capable of doing and becoming.” But such are the wages of repetition. • 2 November 2009