The letters of famous persons generally disappoint. Letters, unless specifically written for the public, are personal in essence. It is one human being in contact with another, sharing things that, often, only the two can fully understand. The letters of great persons are no different. At best, they provide a glimpse into secrets, a chance to hear the unguarded thoughts of public figures. There is the potential excitement of revelation. Occasionally, our desires are satisfied and then some. We come across, for instance, James Joyce writing his wife Nora: “Some night when we are somewhere in the dark and talking dirty and you feel your shite ready to fall put your arms round my neck in shame and shit it down softly.”

In such moments of intimacy, dirty or less so, the aura of fame is stripped away and the person becomes human again. That is also what makes letters boring. Money problems and petty disagreements are the bread and butter of your common letter. A letter makes the world small again, shows a person enmeshed in the day-to-day affairs that everyone understands. Thus, by way of their potentially shocking intimacy or through their potentially overwhelming banality, letters tend to lack the specific elements that are to be found in the actual work of a great artist. Letters, inevitably, are the flotsam and jetsam through which the scholars pick. They contain little meat for you and me.

But this is not always the case. Thanks to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, the letters of Van Gogh can now be perused in total. There is an exhibit running through January 2010 but, more important for those not able to make the trip, a complete online edition of the letters available at vangoghletters.org. The website is simply amazing. The letters themselves are interesting enough on the personal level. Vincent’s last letter to his brother Theo contains the poignant thought, “I’d perhaps like to write to you about many things, but first the desire has passed to such a degree, then I sense the pointlessness of it.” All of the letters to Theo, actually, reveal a thoughtful, sensitive, and loving brother.

In this, Vincent van Gogh is one of us. We see him as a human being negotiating his way through a complicated world. But there is something more, some portion of his greatness contained in these letters. This makes them unusual. Van Gogh is talkative, especially in the letters to the

artist Emile Bernard, about his art, about what he sees himself doing as he paints. In a particularly revealing letter to Bernard from June 7, 1888, Van Gogh writes:

I’m going to put the black and the white boldly on my palette just the way the colourman sells them to us, and use them as they are.

When — and note that I’m talking about the simplification of colour in the Japanese manner — when I see in a green park with pink paths a gentleman who’s dressed in black, and a justice of the peace by profession (the Arab Jew in Daudet’s Tartarin calls this honourable official shustish of the beace), who’s reading L’Intransigeant.

Above him and the park a sky of a simple cobalt.

Then why not paint the said shustish of the beace with simple bone black and L’Intransigeant with simple, very harsh white?

Because the Japanese disregards reflection, placing his solid tints one beside the other — characteristic lines naively marking off movements or shapes.

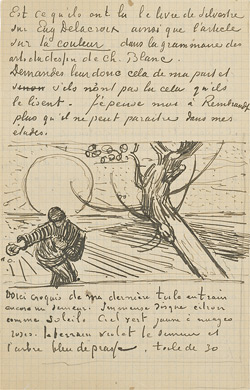

Van Gogh is distilling his entire process here into the simplest of terms. Strong lines, the contrast between black and white, and the juxtaposition of color in pure blocks. But even more striking than Van Gogh’s sharply worded descriptions are the sketches that go along with them. Van Gogh used his letters as a kind of sketchpad, working through ideas by drawing on paper as he wrote about them.

In the same letter to Bernard quoted above, Van Gogh includes a sketch to illustrate what he is doing. He draws a row of cottages using his typical strong black lines. He then labels what the colors will be in the actual painting: blanc, rose, chrome 2, etc. We know the painting today as “Row of cottages in Saintes-Maries” (1888). In a wonderful feature on the website, you can superimpose the painting over the sketch in the drawing. The sketch turns immediately into the full painting with the simple filling in of color. The amazing thing is the simplicity of it all.

The lesson of these letters and their sketches is the hard-fought road to that simplicity. By 1878, Van Gogh is starting to really get it. He writes his brother and includes a sketch of “The Au charbonnage café.” It’s a sketch that could easily be picked out as a signature Van Gogh. Mostly that comes from the thick black lines and the open spaces of white. He writes to Theo, “You surely know that one of the root or fundamental truths, not only of the gospel but of the entire Bible, is ‘the light that dawns in the darkness’. From darkness to Light.” He talks, also, of becoming a Protestant Evangelist in this area of hard working coal miners. He admires the joy with which they descend into the absolute darkness of the mines. He would like to tell them about the “light that dawns in the darkness.”

How different this is from the picture of the crazed artist chopping off his ear for a local prostitute. Something terrible did happen to Van Gogh at the end of his life, some mind-destroying illness. We’ll never know exactly what it was. It is clear, though, that the madness of Van Gogh has nothing to do with his art. His madness, the unraveling of his hold on reality, destroyed his ability to do art, not the other way around. Just a year before his death, he writes to his brother again:

Work is going quite well — I’m struggling with a canvas begun a few days before my indisposition. A reaper, the study is all yellow, terribly thickly impasted, but the subject was beautiful and simple. I then saw in this reaper — a vague figure struggling like a devil in the full heat of the day to reach the end of his toil — I then saw the image of death in it, in this sense that humanity would be the wheat being reaped. … But in this death nothing sad, it takes place in broad daylight with a sun that floods everything with a light of fine gold. … Ah, I could almost believe that I have a new period of clarity ahead of me.

We don’t tend to think of Van Gogh as a painter of clarity. But that is what the letters and the sketches bring out: the simple juxtaposition of strong colors, the battle between black and white, the thickness of the boundaries between objects. Van Gogh the painter wasn’t confused by the world at all; he saw things clearly every time he sat down with the instruments of his art — sober, sane, and precise. • 18 November 2009