The usual obsessive lunchtime topics for a thousand adults in an Antarctic work camp are generally work, Antarctica, and other Antarctic workers. But during my years on the ice, the banter around the dining tables also often referenced the outsized stories of early Antarctic exploration. The heroic Pole-seeking starvation tales of Ernest Shackleton, Robert Falcon Scott, and Roald Amundsen reminded us of the harshness of the place in which instead of “hoosh” — a slurry of pemmican and melted snow, thickened with crushed biscuit — we were eating soft-serve ice cream.

That was the idea, anyway. Even the cynical old hands, the ones who had been around long enough to see the United States Antarctic Program as a bureaucratic boondoggle or a well-played rook in the geopolitics of the Southern Hemisphere, felt a connection to the noble past. We lived on an ice continent that had a mere century of human history, like lunar miners chatting around their cafeteria tables 100 years after Neil Armstrong. Except that Armstrong didn’t have to slaughter seals and penguins to keep his limbs and gums from turning black with scurvy. For us, Antarctic history seemed to provide an ethical framework — whether by comparison or contrast — for all our striving, and for a consideration of why we inhabit the ice and what good might be derived from our actions.

Like the inhabitants of other former frontiers, we Antarcticans like to think that the successes, the failures, the noble or ignoble exploits of our pioneers become essential narratives for those of us who have settled in their footprints. And as I found opportunities to leave the industrial-park confines of McMurdo Station for more remote parts of the ice — camping at -25 degrees Fahrenheit on the East Antarctic ice cap, say — and then sensed the same human insignificance and fragility they experienced amid the vast Antarctic austerity, their storied past provided a literary and historic language by which to understand my experience.

And then I read the saga of Douglas Mawson, and realized all was vanity. Mawson was an Australian explorer who knew more about Antarctic suffering than most, despite that he was more scientist than adventurer. He scoffed at the fame that came with Poles, and while nationalist enough to claim a wide swath of the continent for Australia, he came to the ice seeking facts. “The polar regions,” he wrote, “may be said to be paved with facts… As surely as there is here a vast mass of land with potentialities, strictly limited at present, so surely will it be cemented some day within the universal plinth of things.”

Antarctica, as it turned out, was more emptiness than facts. And a particularly empty emptiness, in the form of a deep crevasse, awaited Mawson and his comrades. After the saga that followed, from which a ruined Mawson would emerge as the sole survivor, he noted that, in the midst of his deprivation, “cocoa was almost intoxicating and even plain beef suet, such as we had in fragments in our hoosh mixture, had acquired a sweet and aromatic taste scarcely to be described… as different as chalk is from the richest chocolate cream.”

Are we Mawson’s descendants or his antithesis? Either way, our lunchtime banter is trapped within an inescapable vanity: We take pride in occupying this rare and hallowed ground, but we do it by reveling in a cozy existence on a continent that could sponsor raptures over the benefits of starvation.

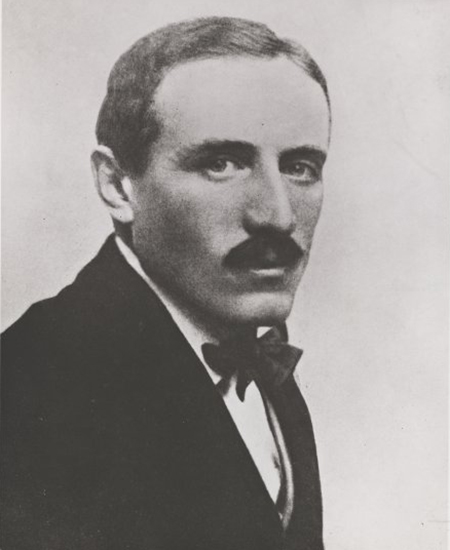

Sir Douglas Mawson with Antarctic exploration equipment (State Library of South Australia).

The crisis began on December 14th, 1912, a sunny 21 degree Fahrenheit day, and by coincidence exactly one year after the South Pole had been reached by Roald Amundsen. Mawson and his companions, Xavier Mertz and Belgrave Ninnis, were traveling east over glacial highlands and mapping the Adelie Land coast. They were the Far Eastern Party, one of six groups that had sledged out from the Australasian Antarctic Expedition’s hut at Cape Denison in early November to explore different areas of an unknown region. Mertz led by ski while Mawson followed, sitting on his sledge and studying notes as his dogs pulled. Ninnis came last, walking briskly beside his sledge. Noting a change in pace, Mawson looked up to see Mertz suddenly stopped, looking behind them at a gaping hole in the empty trail. Ninnis, his sledge, and the party’s six strongest dogs had disappeared into a crevasse. With them went the tent, all dog food, mugs and spoons, and all but about ten days of rations.

Ninnis’s death was the only loss of a human to a crevasse in the heroic age, and represented a death sentence for Mertz and Mawson. Their grief for a friend with whom they wandered “a lonely blizzard-ridden land in hunger, want and weariness,” as Mawson put it, was matched by their fear of “the future which loomed up sinister before us.” As they kneeled and gazed with disbelief into Ninnis’s deep blue grave, only a dying dog, part of the tent, and two weeks’ supply of food were visible on a shelf one hundred fifty feet down, all beyond the reach of their ropes. Mawson had deliberately assigned the best dogs and the most valuable provisions to what he considered the safest sledge. He assumed that he and Mertz, traveling ahead, had taken the greatest risk. But Ninnis had walked onto the snow bridge, his feet punching through where skis and sledge had spread the weight.

Ninnis running alongside his sledge (National Library of Australia).

They were 316 miles from the Hut — Mawson optimistically capitalized it — with little human food, no dog food, and six near-useless dogs — George, Johnson, Mary, Ginger, Pavlova, and Haldane. All but essential weight was discarded. No depots had been laid, so what little they carried was all they had. Their first meal consisted of an ugly broth made from boiling food bags to be thrown away, while the dogs were fed worn-out mitts, boots, and rawhide straps. From then on, the dogs, who had grown strong eating slaughtered seal at the Hut, ate only each other.

On their first grief-stricken, desperate day homeward, they covered 27 miles in a reckless dash, plunging across crevasses with what Mawson called “a tense heart and a grim sense of unreality.” Mertz configured a tent out of the old tent cover and used sledge runners and skis for poles. It barely fit the two men. Mugs were made from tins, and spoons were carved from the sledge frame. The first dog to go, George, was shot and slaughtered for dogs and men. Mawson noted that George’s meat was so stringy, lean, and tough that it exhausted the men’s jaws, providing meals “of the sketchiest character.” The other five dogs would be no better. This may have been particularly difficult for Mertz, as he had long been a vegetarian.

They tried to forget about food as much as possible, ate no lunch and did not stop to melt snow to stave off dehydration. Poor “disreputable” Johnson was next, but was so rancid that in subsequent days Mawson and Mertz would define their day’s luck by how much Johnson they pulled from the bag of mixed dog meat. Things got worse as they agreed to mete out their meager food allowance according to how many miles they made in a day. Stormed-in days in the cramped tent were a hungry, claustrophobic hell.

Mary tottered and fell. Haldane, too emaciated for his harness, followed suit, but not before nearly falling into a crevasse. “Fortunately,” Mawson wrote, “I was just able to grab a fold of his skin at the same instant, otherwise many days’ rations would have been lost.” Because the rifle had been tossed away as excess weight, Pavlova had to be killed with a knife, in what Mawson acknowledged was “a revolting and depressing operation.”

Confined by weather to the tent, the men struck on an idea: Boil the dog carcasses for hours so that even the gristle, sinews and paws turned into jelly. This made better use of the bones, extracted the marrow fat, saved the men time for future meals, and lightened their fuel load. Mawson cheerfully described “a delicious soup made from some of Pavlova’s bones cracked open with the spade.” By the time Ginger — their final dog — fell to the knife, Mawson and Mertz were on a starvation diet of about 14 ounces a day, less than half their usual 34 ounce ration, most of it worn-out dog meat of little nutritional benefit. Food dreams haunted them. Hopes for their survival on a miserable Christmas were toasted with dog soup. Only the dogs’ livers were easy to chew, but as Mawson put it, “trouble of a new order was brewing.”

Mertz fell apart, physically and mentally. Mawson first realized the seriousness of his friend’s disorder when Mertz “lost appreciation of the biscuit.” Every expedition that had dared the Antarctic interior carried biscuits that the starved men grew to love. Amundsen noted that his team “positively caress the biscuits before they eat them.” Mertz’s loss of appreciation surely was a sign of madness. Neither Mawson nor Mertz showed clear signs of scurvy, though they were obviously starved and malnourished. Yet they could not explain the shedding of skin and hair. Mawson lost even the soles of his feet. Both suffered severe abdominal pains and Mertz’s behavior grew erratic, eventually leading to a complete breakdown of body and mind. Marches of one or two miles were all he could do, then nothing at all. Mawson tended to Mertz, all the while begging him to keep walking as their hopes of survival slipped away.

Decades later, an analysis of their symptoms and Mertz’s sudden decline suggested a condition known as hypervitaminosis A. Toxic levels of Vitamin A bioaccumulate in the livers of many polar marine creatures, and in husky livers if they are fed those creatures, as the vitamin produced by marine algae passes up the food chain. 100 grams of these livers would poison an adult human, and the two men ate six livers between them. It’s possible that Mertz ate more than half, accepting Mawson’s offer to share. In a strange frenzy near the end, this Swiss ski champion bit off the frozen tip of his own finger. Dysentery and raving fits characterized his last hours in his sleeping bag, before he died next to an exhausted, grieving, sleepless Mawson.

Dr. Xavier Mertz (National Library of Australia).

In a heartbreaking bit of understatement, Mawson wondered “if there was ever to be a day without some special disappointment.” He cut the sledge in half and dumped absolutely everything unnecessary for survival. His raw feet hurt so much while crossing the bare ice of the Mertz Glacier that he chose to walk along the soft surface of bridged crevasses, tempting fate as only a miserable man can. He later fell into a crevasse, gave himself up for dead, but then in a final heroic push of adrenalin, hauled himself up by his harness. He was motivated by a single regret, “that after having stinted myself so assiduously in order to save food, I should pass on now to eternity without the satisfaction of what remained.”

He questioned whether it was better to live or die. On one hand, he could continue to starve and move forward with little hope, or he could “enjoy life for a few days, sleeping and eating my fill.” Whether tenacious or masochistic, he went on, and by the time he was down to twenty small pieces of dog meat, half a pound of raisins, and a few ounces of chocolate, with blizzards literally burying his tent up to the peak, he finally had his day without disappointment.

On January 29th, he stumbled onto a cairn left just that morning by a search party. He attacked the food bag cached within it, scattering its contents on the ground. The search party had turned back to the Hut, and Mawson followed, knowing he could be there in two difficult days. He reached Aladdin’s Cave, an excavated hideaway and depot in the glacier five miles away from the Hut, and feasted again. Three oranges and a pineapple were proof that the Aurora had arrived from Australia. But when Mawson turned to finish the last five miles, a shrieking blizzard blew in and lasted an entire week.

At storm’s end, as Mawson limped within sight of the Hut, he could see the Aurora leaving Antarctica for the year. Perhaps it was just as well, for despite the care of the men who had volunteered to stay behind, Mawson took months to recover his wits and health. Sailing home immediately through difficult waters might have killed him. Not until ten months later did the Aurora appear again to bring him home.

•

Of all Antarctica’s early expedition leaders, only Mawson returned to the ice after the heroic age, or survived to see the dawn of the modern age. Knighted after his horrific ordeal on the AAE, for service to science and the Empire, Sir Douglas would later lead the British Australian New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE) of 1929-31, then advised the Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition (ANARE), a government department set up in 1946 to secure and support Australia’s claim to some 42% of the Antarctic (a claim rooted in Mawson’s work on the AAE). And in his final years, he was able to bear witness to the scientific settlement of the ice continent that had tried so hard to kill him.

By the time Mawson died in October of 1958, 12 nations had built 56 stations, many of them occupied year-round ever since. And while this settlement heralded major advances in the study of south polar auroras; cosmic rays; geomagnetism; glaciology; gravity; ionospheric physics; meteorology; oceanography; seismology; biology; and medicine, it also meant that Antarctica would never again be without hungry human residents. That hunger, however, would never be the same. There remains a certain danger and modest deprivation in Antarctic work, but always with certain safety margins established by modern science, steel icebreakers, and the miracle of aviation. There have been deaths, certainly, but the bodies were all well-fed. • 29 November 2012