So 271 “new” Picassos have been discovered. They were living with a former electrician of Picasso’s, who claimed that, near the end of his life, the artist gave the works to him as gifts and as payment. Picasso’s heirs, of course, are suing and charging the man with theft.

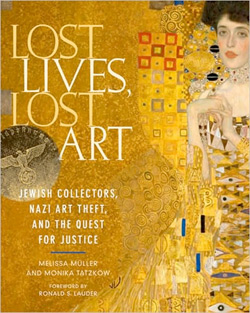

- Lost Lives, Lost Art: Jewish Collectors, Nazi Art Theft, and the Quest for Justice by Melissa Müller and Monika Tatzkow. 256 pages. Vendome Press. $40.

- The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Family’s Century of Art and Loss by Edmund de Waal. 368 pages. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. $26.

Two hundred seventy-one new works by Pablo Picasso, ranging from 1900 to 1932. New works from his blue period, a new portrait of his first wife, Olga. You can hear the auction houses warming up their gavels, can’t you? Scholars lining up to recalibrate the Picasso timeline. It’s unclear so far who has been wronged here — the heirs, who possibly should have inherited these works after Picasso’s death? The electrician and his wife, who apparently never tried to sell and profit from these pieces, despite their value reaching the tens of millions? The public — historians, museum-goers, scholars, art lovers — who were not even aware they were missing such a large part of Picasso’s oeuvre? The elderly electrician has been arrested and shamed by the heirs for “concealing” these great works. The works have been confiscated from the electrician’s home as everyone debates where their new home should be.

When it comes to art, “private” and “public” take on confused, tangled meanings. In Lost Lives, Lost Art: Jewish Collectors, Nazi Art Theft, and the Quest for Justice, Melissa Müller and Monika Tatzkow show the extent to which European museums profited from the chaos following World War II. But there is one particular case — the story of Gustav Klimt’s “Adele Bloch-Bauer I,” or “Dame in Gold” and the journey it took following the devastation of the war — that highlights these tricky issues of property.

Adele Bloch-Bauer was a Viennese art collector in the early 20th century. A friend (and possibly lover) of Klimt and a fashionable society lady, she and her husband Ferdinand filled their house with grand paintings, a formidable porcelain collection, and a valuable library. She died in 1918; in regards to the paintings, she wrote in her will, “I ask my husband to leave my two portraits and four landscapes by Gustav Klimt to the Österreichische Galerie in Vienna after his death.”

Between 1918 and Ferdinand’s death in 1945 came World War II. The Jewish art collectors in Vienna were particularly vulnerable to the seizure of private property. The economic troubles of the 1920s and ’30s coupled with the flourishing of anti-Semitic newspapers and speakers created a dangerous climate for Jews who possessed or displayed any wealth at all. On March 11, 1938, the Austrian government dissolved itself and allowed German troops to enter the country. As Edmund de Waal writes in his beautiful memoir The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Family’s Century of Art and Loss, “It is as if a switch has been thrown,” and suddenly his family, the Ephrussis, are no longer citizens of the Austrian republic. That night, chaos rained:

The sound of things breaking is the reward for waiting for so long. This night is full of these rewards. It has been a long time coming. This night is the story told by grandparents to grandchildren, the story of how one night the Jews will finally be held accountable for all they have done, for all they have robbed off the poor… And across Vienna people help themselves to what should be theirs, is theirs by right.

After the chaos came the bureaucracy. The Reich confiscated every valuable collection it could find, and that included the Ephrussis and the Bloch-Bauers. Art historians were brought in to systematically sort through all of this new plunder. Fritz Dworschak, the newly made Kunsthistorisches Museum director, announced with excitement that the upside to this terror is a “singular, never-to-be-repeated opportunity for expansion… in a great number of areas.” Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer was an obvious target, not simply for his valuable collection — and as a board member of local museums and a generous patron he was quite visible in Viennese society — but for his outspoken politics. He was forced to flee in 1938, first to Czechoslovakia, then to Paris before finally settling in Switzerland. His house in Vienna was occupied by the German railroad company, and all property he left behind was seized and divvied up between museums, Hitler’s personal collection, and the collections of other party members.

Ferdinand only outlived the Nazi regime by a few months — he died in November 1945. In his will he left everything to his niece and nephew, although he was not optimistic that his possessions added up to anything. Still, he expressed optimism that perhaps the two major portraits Klimt painted of his wife and a portrait of himself by Oskar Kokoschka could still be returned. But Austria was a tricky place immediately after the war. Austria was playing the role of “the first victim” of German tyranny, and many of the people who held positions of power in the post-war government had profited greatly from the seizure of Jewish property, either directly or at auction where great works were sold for a fraction of their value. As de Waal reports, President Dr. Karl Renner stated, “Restitution of property stolen from Jews… [should not] be to individual victims, but to a collective restitution fund… in order to prevent a massive, sudden flood of returning exiles. Basically, the entire nation should not be made liable for damages to Jews.” If Jews couldn’t produce proper documentation of what was stolen from them — if they didn’t have a receipt — well, tough luck.

The Klimt paintings were so valuable that it was not difficult to track them down. But Austria was not willing to part with them. Using Adele’s will as evidence, the Österreichische Galerie claimed they were the proper owners of the work. Furthermore, the Austrian government held the Bloch-Bauer estate hostage, refusing to grant export permits to ship everything else to the niece and nephew in Canada unless the heirs relinquished their claim to the paintings. Unsure of their own rights and unable to afford a costly court battle, the heirs agreed.

Austria remained a very problematic place for Jewish survivors. It wasn’t until the 1998 Art Restitution Act that the nation began to address some of these ownership issues. And when Maria Altmann, Bloch-Bauer’s niece, used that act to again lay claim to the Klimts, Austria again stonewalled. It took years of expensive trials, the intervention of the United States Supreme Court, and the assistance of the Commission for Art Recovery before Austria handed over the paintings to Altmann. This was despite attempts by Austrian bankers, collectors, and businessmen to convince the government that the Klimts were national treasures and belonged in Vienna. (Klimt is of course a natural representational artist for Vienna, his work being physically beautiful yet slightly cloying and sentimental.) The paintings immediately went on the market, and the golden “Adele” sold for $135 million. Each were sold into private hands, where they remain.

Edmund de Waal’s family lost countless works of art and an enormous library of rare books during the war. Thanks to the devotion of a Gentile servant named Anna, however, they were able to rescue a large collection of netsuke — miniature Japanese carvings that were very fashionable in turn-of-the-century Paris. She smuggled them in her pockets past the Gestapo who had set up shop in the Palais Ephrussi and kept them hidden in her mattress until the end of the war. From there they were returned to the family, and stayed with de Waal’s uncle when he relocated to Japan. After his death, de Waal meant to take them back home with him to London. But not everybody agreed, as de Waal relates:

“Don’t you think those netsuke should stay in Japan?” said a stern neighbor of mine in London. And I find I am shaking as I answer, because this matters… Objects have always been carried, sold, bartered, stolen, retrieved and lost. People have always given gifts. It is how you tell their stories that matters.

The Picassos will make their way back into the world, out of an electrician’s house and into the auction houses. Whoever ends up putting the money down, and whoever gets to pocket that money, they do not own the story of the painter, or the emotion of staring up at the golden “Adele.” The human stories of theft and bravery are about justice and honor. The art itself will endure any squabbles over property, or any nationalistic claims. • 1 December 2010