I wrote a little essay about Christmas for The Smart Set in December of 2007. It began with the sentence, “In defending Christmas I have nothing to say about Jesus Christ, a terrifying and influential historical figure who, I confess, has had little impact on my life.” An amusing enough line for an atheist with no great hostility to Christianity or any other religion.

Then a funny thing happened. In the intervening years, I became a Catholic. Currently, I go to Mass every morning at Saint Mary’s in Schwenksville, Pennsylvania. That “terrifying and influential historical figure” has managed, after all, to have quite an impact on my life. That’s the danger every writer faces. Publish your thoughts for long enough and they will eventually come back to haunt you. This can be painful. But it can be a hot and cleansing pain. We write in order to project our sense of self out into the world, to make it manifest. And then, over time, those same “projections of self” come back round to destabilize and embarrass us. I cannot read my Christmas essay without squirming in my own skin. It is a delicious squirming, when I think about it. It is a squirming that collapses pretense.

Oh Lord, have I ever gotten anything right, one damn thing?

I’m not sure, though, that I was completely wrong to write that opening sentence in 2007. The fact that Jesus Christ was an “influential historical figure” is a simple truism. “Terrifying” is the more troubling word. What did I mean by that? It is, in retrospect, a strange word for an atheist to use. Why would I have been terrified of Christ? I meant it with a certain amount of tongue in a certain amount of cheek, of course. I meant it, even, as a sort of insult, though a respectful sort of insult. I meant that there is something absurdly and unbelievably demanding about Christ. I meant something stronger too. I meant that if a person were to do something foolish like pay attention to Jesus Christ, take him at his word, then it would have significant consequences. It would turn your world upside down. I was right to be terrified of that. I didn’t want my world turned upside down, because I thought I had it right side up. But then my world was upended. I don’t stand on the same ground I used to stand upon. For me, it is constantly strange to be a Christian, constantly discomforting, constantly ass kicking. “You shall know the truth,” wrote Flannery O’Connor, “and the truth shall make you odd.”

So I knew something after all when I wrote that Jesus Christ is terrifying. I just didn’t know what I knew.

•

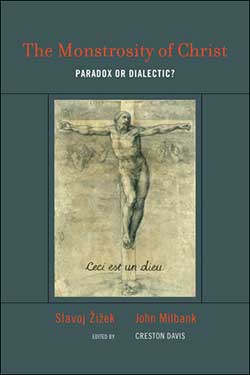

There is an unusual book written by two men: the Christian theologian John Milbank, and, rather improbably, the zany atheist philosopher Slavoj Zizek. The book is called, The Monstrosity of Christ. I reference the book since the idea that Christ is “monstrous” is, I think, not far from my own hazy notion in 2007 that Christ is “terrifying.” Zizek thinks that Christ is monstrous because he forces us to abandon that old idea of God as hovering above the world, checking in and taking care for it. The problem with that conception of God, for Zizek, is that it prevents us from seeing:

The full engagement of God in human history which culminates in the figure of the ‘suffering God’: from a proper Christian perspective, this is the true meaning of the divine Trinity — that God’s manifestation in human history is part of his very essence. In this way, God is no longer a monarch who eternally dwells in his absolute transcendence — the very difference between eternal essence and its manifestation (the divine ‘economy’) should be abandoned.

God, for Zizek, is nothing but the Incarnation. There is no transcendent God left over. Jesus is a monster because he takes away every comfort of the beyond and leaves us in a world of pure immanence.

Milbank responds with a long discourse on the history of philosophy. But it boils down to a simple point. Milbank thinks there is a transcendent God, even after God’s incarnation in the human flesh. Much slinging of Hegel and Duns Scotus and Meister Eckhart ensues. Massive and heavy concepts are thrown around. But the poles of the argument are straightforward. On Zizek’s side, a Christian atheism with a monster Christ who dares to place us in a world in which “this is it” and there ain’t nothing else. On Milbank’s side, Christ is the God-Man in whom reason itself becomes incarnate. This is the monstrous paradox that shakes us up and forces us to acknowledge the divine. Since it doesn’t make sense that reason would become incarnate, it is only accessible, in the end, to a kind of poetic leap. God is always beyond our reach, even though He is also right here.

At the end of Zizek and Milbank’s book, Zizek writes: “This is… how I would love to be: an ethical monster without empathy, doing what is to be done in a weird coincidence of blind spontaneity and reflexive distance, helping others while avoiding their disgusting proximity. With more people like this, the world would be a pleasant place in which sentimentality would be replaced by a cold and cruel passion.”

This is a strange and upsetting desire to hear about. Is Zizek channeling the real voice of a terrifying Christ here? John Milbank speaks the words of a theology that I can understand and endorse. But Zizek speaks with the wild words and destabilizing thoughts that knock me around the way Christ’s words sometimes do.

“I want to come and follow you, Christ, but I have to bury my father first,” says a man to Jesus. “Let the dead bury the dead,” says Christ, dismissing him, dismissing everyone who has ever tried to live a normal life. “And by the way, you should hate your mother and father and everyone else who keeps you away from me,” Jesus adds. “God is like a harsh creditor,” says Christ. “God is like an old woman who looks for a dropped coin.” “God is like an obsessed shepherd who neglects the flock for one lost sheep.” A cold and cruel passion.

•

There is another book. It is by the Protestant writer and preacher, Frederick Buechner. I don’t think Buechner is read very much anymore. But his essays and novels were once reviewed in places like the New York Times Book Review. In Telling the Truth: The Gospel as Tragedy, Comedy, and Fairytale, he writes, “There would be a strong argument for saying that much of the most powerful preaching of our time is the preaching of the poets, playwrights, novelists because it is often they better than the rest of us who speak with awful honesty about the absence of God in the world and about the storm of his absence, both without and within, which, because it is unendurable, unlivable, drives us to look at the eye of the storm.”

“Awful honesty” and the “eye of the storm.” Here we are again in the realm of the terrifying and the monstrous. Who among us really has the stomach to face the fact of God’s absence in the world along with the incredible longing that absence creates? Jesus seems to want us to sit with that terror, to immerse ourselves in the tragedy of the world and to have no answer for it. To have no reply whatsoever. Finally, to surrender to that tragedy.

According to Buechner, when you’ve done that, when you have surrendered to the unbearable tragedy, your next act will be to laugh. It will be terribly funny.

There is a story in the beginning of John’s gospel where Philip brings his friend Nathaneal to meet Jesus. Philip tells Nathaneal that he thinks Jesus is someone special, someone foretold by Moses and the prophets. “Really,” says Nathaneal, “could anything good come out of that stink hole Nazareth?” (Nazareth having been known at the time as a place mostly filled with scumbags.) Later, Jesus sees Nathaneal coming toward him and says, “Here comes another clever Israeli.” Nathaneal asks, “How’d you know who I am?” “No great trick,” says Jesus, “I saw you sitting over there under the fig tree next to Philip.” “Wow,” says Nathaneal, “you really are the King of the Jews, having seen me under the fig tree and all that.” Jesus says, “And what a great disciple you will make, believing I am King of the Jews and what-not just because I saw you under a fig tree.”

“Pretty soon,” Jesus goes on, “a bevy of angels will descend on us.” They both have a laugh.

The situation wouldn’t be so funny if it weren’t true. Jesus is the Christ and he really is the King of the Jews — just not like anyone expected. He didn’t come to rule the land. He came to die like a pathetic criminal. Blessed, says Frederick Buechner, is he who gets the joke. But you don’t get to laugh unless you face the tragedy first. The tragedy is the set up for the punchline. The tragedy, says Buechner, is the inevitable. The comedy is the unforeseeable. Who could have ever guessed that God would come into the world as a doomed bozo from Nazareth? The Apostles can never truly believe what is in store for them. They think the Messiah is going to fulfill all their worldly desires. They tromp around the desert having arguments about who is going to be the most powerful and favored. “Don’t you realize, my beloved idiots,” says Jesus, “that we are all going to die like dogs?” And that’s the reward. That’s the good part. Hilarious stuff. Terrifying.

•

In my 2007 essay, I turned immediately from my dismissal of Christ as “terrifying” to a memory of my sister. Here is what I wrote:

I have a particularly vivid memory of a childhood Christmas during which my sister would stalk the Christmas tree day after day counting presents. On the final day she made a stack in the middle of the room. On one side were the presents with her name on them and on the other, those with mine. She tallied them up. The number was not to her liking. I can still picture the stunned calm as she counted and counted again. But there was nothing to be done. It was clear that my pile was two presents larger than hers. I think it was the “two” that really bothered her. A difference of one is one thing, a difference of two is quite another. When there was nothing more to be done she gathered herself up, collected her faculties, as it were, and then proceeded to throw an epic and violent fit. Right there. She screamed and raged, she tore paper and hurled objects. Her little face took on the specific pallor and twist of mythical figures, semi-human things on frescoes buried in ruins — the shards of lost time. She dashed her head, as only she could, on the kitchen floor, her beautiful blond curls bouncing up and down against the tile and mixing with the tears and saliva. She grunted things that couldn’t be understood. I say again that this is one of the clearest memories of my childhood. She was magnificent, glorious, as she took up arms against a sea of troubles. She was having no bullshit whatsoever. She wanted the presents that were due her.

I suspect that it causes my sister some distress to read those lines. That is another problem with writers. We don’t just carry our own pain and discomfort into the public sphere, we carry the pain and discomfort of our loved ones, too. But I hope that she can see the love and the admiration in those lines. Her rage was never really about presents, never about material objects as material objects. Her beautiful rage was deeper than that. Even as a little child, her rage reached down into that murky place where we are stunned by the outrage of existence itself. My sister has always reminded me of the ancient Greeks in her capacity to leap from the small indignities of life into the indignity at the root of it all, the fact that we are thrown, unrequested, into the turmoil of existence and must play out the dealt hand, living it all the way through as this specific creature and none other.

Interestingly, the celebration of Christmas is the celebration of the fact that God took this same leap. Into the flesh he leapt, foolishly. Literally, it is the fool’s leap. There is no way to do it wisely. And in the Garden he cried about it, the experience being so painful and strange and scary. And on The Cross he had the audacity to be pissed off at himself for having done it. “Why did I forsake myself?” A tragi-comic punch line if ever there was one. He spoke no answer. The answer can’t be put into words anyway. Terrible, terrifying, and just right. • 16 December 2013