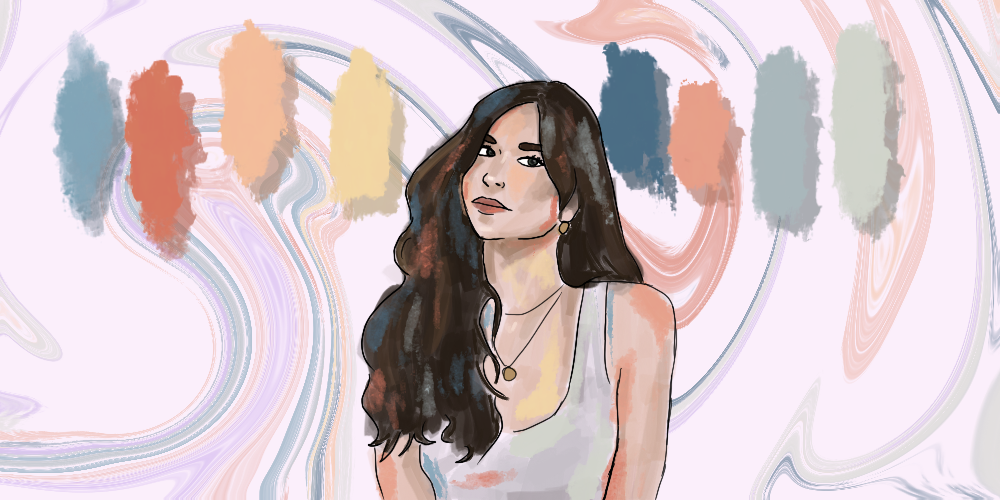

When I discovered her work, I was searching for a different Madeleine Gross. The days of lockdown wearied me; I lay in bed, at night or during the afternoon or morning (time was unbroken and the same), swiping to find how others had changed. I sought one of my many now-anonymous former coworkers from a restaurant in the suburbs of Chicago. Instead, I found the Madeleine Gross at the top of the search list, the one with 40,000 followers, the 28-year-old artist whose images moved me — something I thought could never happen on social media — by their beauty, originality, and flair.

In contrast to the other photos on Instagram, Gross’s offer the promise of seeing ourselves in others. Instagram wounds the young because they cannot see themselves at all — not in the glute-perfect poses or the Adobe-d silhouettes. Gross’s art heals wounds: it waits for us like the reprieve of vacation and restores us in vibrant strokes of color painted on photographs taken by the artist in travel. This distinguishes her photographs because the painted bodies become invitations to ambiguity, to see ourselves in each frame, and to question our supposed sureness in memories and sights. This work reaches across difference, holds ample selves. By scraping vibrant paints across pictured landscapes, Gross paradoxically reproduces her feelings in the viewer, who would not otherwise experience jubilance at seeing yet another photograph of a beach or cobbled street.

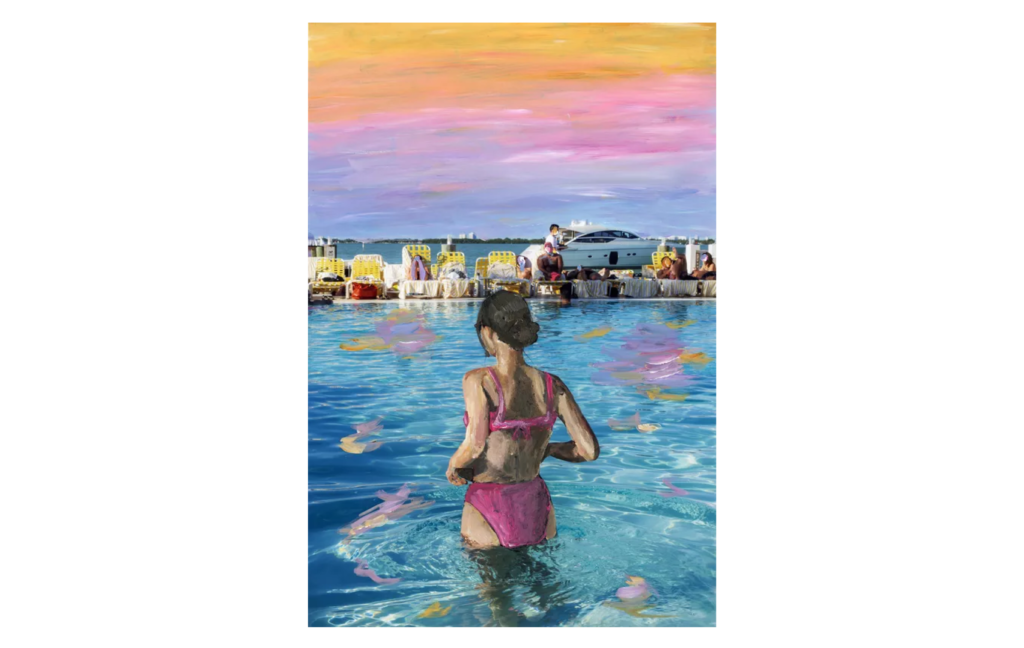

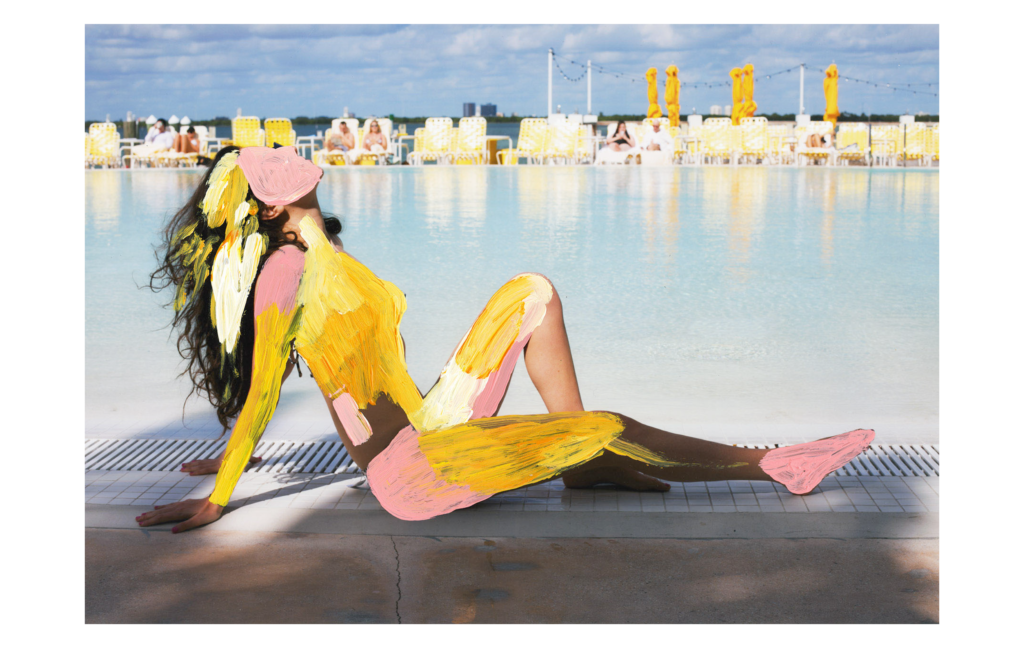

Although she has only experimented with the form since 2014, Gross’s unique style has already produced works that appear iconic: “Blue View” and “Masada, 2017,” with their streaks of paint that seem as if they were extracted from the landscapes themselves; “Candy Apples,” with the young lovers in paint holding each other under the grand Ferris wheel and neon lights; “Spa Drinks,” which turns our gaze to the smiling woman with the white and yellow towel wound around her hair; “Sun Screen,” which presents a woman staring directly into the eyes of the viewer, nobody around aware of her contours of paint and intimate gaze; “Two Lovers,” painted onto the sea in the brilliance of sunset and embrace; “Miami Sunset Silhouette,” the outline of a woman reposing over the image of the sea she dominates and holds within her; and “Miami Dream 2020,” with its warms and cools, its layers of yellow and tangerine and light rose and pink, its illusive movement between photograph and paint, its dapples of light, and a painted woman’s back turned, her elbows bent in adjusting her bathing suit, and that crescent glimpse of her face looking out on the sea. It’s difficult for me and even for the artist herself to describe these works because they perfectly express their ideas and moods through their forms. You do not need textbooks or magnifying glasses to appreciate this art: gaze on it and you will feel and believe.

But I will attempt to describe. A bright lightness characterizes Gross’s painting-pictures, with their seasides, their vacationers and palms, their ribbons of acrylics, their flamingo pinks and peach tans and sun yellows and cotton candy blues. The images’ calm vibrancy contributes to their accessibility and Instagrammability. This is art for good vibes, made for the world-weary and social media anxious.

Gross’s art reaffirms that we primarily perceive people and places through our imaginations and feelings. Paris is a city of the mind. Gross dramatizes this in her Parisian Daydream prints: the squiggles of clouds, the blue-painted skies, the brushstrokes, and daubs of purple in the figures of strangers. If I viewed her photographs without the paint, I would glance over the backs of strangers and the narrow cars almost stacked on one another like the buildings lining the rue. But Gross’s artworks halt me. They lead the eye to blooms of paint and cause us to internalize the feeling that many of us share when we arrive in Paris: the wonder, the dream of something old and new.

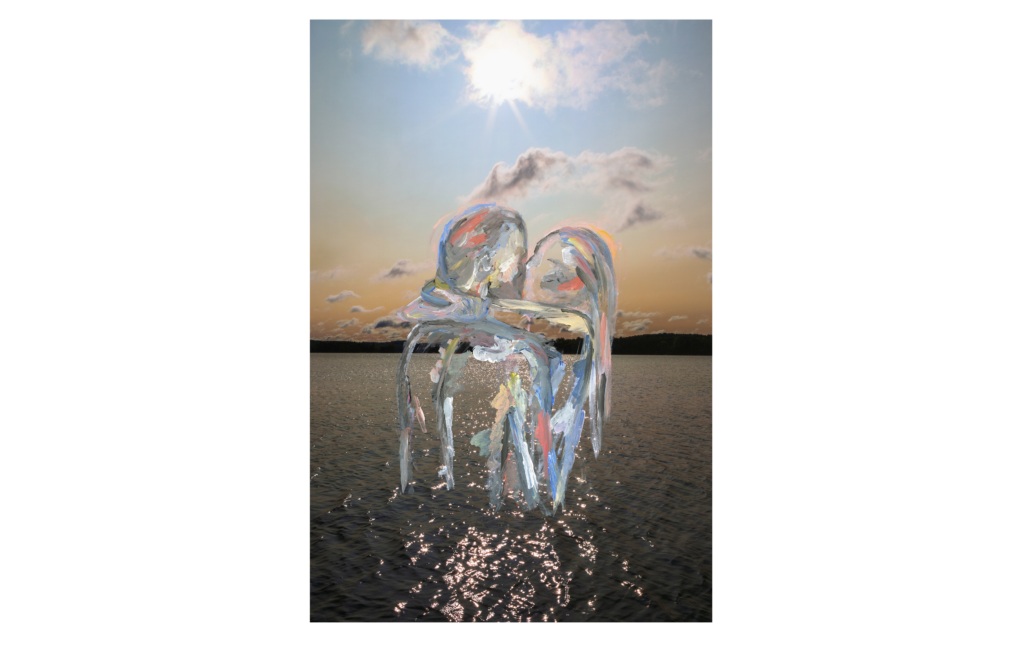

At the same time, by painting over photographs of her trips, Gross fills each image with shaped recollections and dreams. We might feel romance when we walk through alleys in Paris, but we might also feel nothing, and in remembering the trip and looking back on our photos, we fill the images with fantasies of pure joy and hopes for how things had been. Do we see what others see, or do we see what we wish to see? How much of our memories are merely pleas against reality? Gross’s abstractions ask these questions. And “Sunset Kiss 2020” epitomizes them: the heavy navy of sunset coming down on deep orange against flitting clouds; two lovers painted against the image, in translucent outlines, ornamented with feathers of color, their kiss and embrace almost too perfect to last. This is an image that anyone in love can admire but that anyone crawling in the ruins of broken love can feel — as outlines to fill in their dreams, as a hope against disappointment, the dark navy, time.

What is it about Gross’s work that moves me so much? It is the aesthetic boldness, the drawing the eye with leading lines up a photographed rue to a painted sky. It is the round shapes and soft shades. It is the joy of color and light, represented faithfully in our dismaying times. It is the outlines of women, who rise above their surroundings in mystery and splendor. It is the complement of hyper-detailed photographs and people painted like impressionistic artworks, which approximates how we live more than any other aesthetic or technique, as we pass through our detailed settings to the experiences of other people, who are explosions of feeling and color and memory and expectation and beauty and love and dream. It is this that moves me: the inner world painted on top of the outer. Images true to both the visual and emotional reality of life. Accepting both, not either-or. The dreamed-of and the lived. The poetic and the mundane. Reality. Art.

Below you will find excerpts from our conversation in early November. I spoke from under towers of books in a small room outside of Chicago, drinking fresh water from a relic of love, while Gross spoke from her cottage three hours north of Toronto, her voice warm and pausing for thought, letting in the occasional noise of art: stones brought from the lake being installed above her fireplace as décor.

Marek Makowski: I want to start with a description I read last week: “Madeleine Gross is a Toronto-based artist who customizes her photographs with paint.” Madeleine Gross is your name; you’re from Toronto; you work with photos and paint. But would you characterize your art as simply customization?

Madeleine Gross: No. I sometimes have a hard time describing my art. I’ve also changed the way I’ve painted. I like the real world — what we see — compared to how we feel in a setting. When you play back a memory in your head, it could be completely different from how another person experienced it. The photos are all my own, and I try to bring back a different narrative or how I felt in that setting to question abstraction versus fantasy and reality, and how much of that is just what we think rather than what we see.

MM: It’s often quoted that you “abstract landscapes but without completely abstracting reality.” What does this mean?

MG: It’s not completely abstract: you still depict, let’s say a beach, but there are these elements of abstraction that completely change the whole depiction of the image or the whole story.

MM: You’ve also mentioned that you only paint on your own photographs. Have you done others’ photos for commission?

MG: I have done it — when someone wants a present for a significant other or something of that nature — but I speak with the person and it’s a collaborative experience. I don’t ever share my commissions because it’s a very personal experience between the collector and myself. They share their story: since it’s not my photo, I like to have a background of what they’d like to convey and what kinds of emotions.

Sometimes it can be challenging because I’m really making art for someone else. One of these girls’ friend’s dad passed away, and they wanted to get the daughter a personalized piece of him. It’s so personal and such a hard situation. I lost my mom, so I was thinking, what would I want? And depicting someone who’s passed, you don’t want to do anything that would make them feel sad. It’s so personal, so I had to talk to them and understand what she would want.

MM: You’re working with abstraction, you’re engaging with personal memories; when did you figure out entering that space between painting and photography would allow you to explore complexities that just painting or just photography wouldn’t?

MG: We’re constantly seeing images. On Instagram we see other people having fun or maybe we get jealous, so I wanted people to be more connected. Rather than just a gorgeous image — thinking, oh, I want to go there, the photo looks nice — maybe the paint makes it more personal. It’s not just my experience, but the viewer can connect to it more. When you look at an abstract painting, everyone sees something differently, so I’m connecting that with a setting they might have seen before.

MM: I’ve noticed that, in some of your works, the shades of color in the painted bodies match the colors of the environments. For me, this suggests that we might be made of the places around us, or we are made of what we see. Some appear to be imposed on the settings; others look like they emerge from them. How do you approach representing the individual figure and their environment?

MG: It changes with each image. Sometimes, when I shoot something, I go back to look at it and know exactly what I’m going to do. So much is about the feelings I get when I first look at an image. A lot of things are fantasy and daydreaming. We live so much in our heads, so it’s asking what’s real and what’s not. You can think about something, think about it so much, and think that it actually happened, because you want something so badly, like after heartbreak. . .

When I take pictures of a landscape, sometimes I think about Rothko, how it’s two different blocks of color. A lot of people say to shoot your landscapes in landscape, but I like it so much in portrait because I’m treating each photograph as if it’s a canvas. I print them out large-scale and, by each layer of paint, the photo often transforms into something completely different.

MM: Your work features female silhouettes, and sometimes they’re set dominant over a sea or a sky or some other grand landscape. Why these figures in particular? What do they represent for you?

MG: The female figure is art in its own. I’m totally inspired by the female form and the way the body moves. Sometimes they can be self-portraits, or a higher being, or just the feeling of love. A lot of them are self-portraits, so it’s of myself in a setting.

MM: Many of your photographs come from those settings, and they dramatize private memories: all the beaches, the fairs; “Joshua Tree Road Trip”; “Luncheon on the Grass, in Central Park”. It’s as if the painting allows you to transform a memory, or making the art allows you to engage with memory in a different way, to process personal moments through imagination into the public.

MG: It alters my memory, too: within the trip and within these memories I’m creating something new, so it keeps evolving. Some of them are pictures that people have taken of me, so I set up the camera and someone takes these photos, and I don’t really think about it as myself anymore. So many people keep asking me, “are they self-portraits?”, and it really isn’t me, it’s the spirit or the representation of femininity. But then I remember, actually, it’s myself that someone is purchasing and putting on their wall.

MM: One of my favorites is “Sun Screen.” In the background people talk, splash in the water, play with paddles, and the foreground confronts the viewer with a strikingly personal moment, a painted-over female figure staring straight at the viewer for a photo. It feels like an intimate moment between the person holding the camera and the person posing. That gaze holds great emotional intensity and shows how the others are unaware of the person, or the artwork, standing there on the beach. We wander through our lives unaware of the powerful, intimate relationships between people; unaware of their bright blues and yellows and pinks. How did you conceive that, and how do you see this relationship between the personal and the public in your work?

MG: I like that one a lot, too. That’s actually myself, and my best friend Abby took it. We were in Israel together — and we’ve grown up together, and she went to art school with me — and I’m not so comfortable being in front of a camera, so for me to do that I have to be with someone I trust and feel good with. And I love it when people aren’t looking: they’re in their own world, the two girls [in the background] are talking, and I’m so still. The colors are bright and warm, the blue matches the ocean, and it’s all between the setting and the person and how we all connect and interact with each other.

MM: How would you describe your artistic progression?

MG: Before, it was just paint strokes: I liked to use these palette knives, and sometimes I still do, but I wanted to start doing something differently. It was little simpler, and I would either want to contrast the image or use complementary colors or use white paint to make it stand out. Now I paint the whole image or do half. I get inspired by impressionistic painters, and it’s so much experimenting. I only started doing the figurative work two years ago, and I never did anything like that. I’m just painting a figure out of nowhere — there’s nothing underneath.

MM: In “Sunrise Painting,” we find an artist seated at an easel and painting the vista — all in paint, while the background is the photograph of the sunset. How does this work consider us to view the artist?

MG: When I see something so beautiful and am immediately inspired by it, I wish I could go out there and pull out an easel, so I liked how they’re already depicting it while it’s happening. It’s kind of a self-portrait of my process and what I like to depict and just being in that setting and immediately creating it into something physical.

MM: You’ve said in an interview that you create art to free yourself from “grief, depression, and anxiety.” You come to the canvas with these feelings but produce extraordinarily colorful and vibrant works. What is it about the artistic process that allows for this transformation? What is it about applying paint to picture?

MG: It takes me to a different world, but it’s also nice because in life we don’t really have control over anything, and in my art I can completely control this narrative and the way that I’d like the world to be or the way that I’d like things to happen in my life. I’m in a different state where I feel that there’s no fear. I can be fearful, but when I’m creating my work I can feel freer and not so scared.

MM: Have you considered representing sadness, or is it necessary to keep things positive?

MG: I think that the pain, or grief — anything, I turn it into something else. A lot of these memories are places I was with my mom or I remember my mom being there. So I try to put the feeling that she’s here into my work. If I made work that was harder . . . I want to get into that, but I have a hard time sometimes. I think that it’s difficult, and I might get distracted, or sad. I try to just be focused and create work that feels good.

MM: Do you also subscribe to the belief that by creating an artwork you might be creating something that will outlast you or that will make certain moments or people eternal?

MG: I hope so. I like to think that whatever I’ve created will carry on. I also love the way that people see things so differently. Someone will say what they felt when they saw my art, and it’s so special to hear how other people see it. I like that it’s a personal experience, but I know that as years go on, everyone’s going to see something different and have their own experience with it. One of my most popular pieces is “Two Lovers,” and someone said, I felt like they were drowning. Everyone has such a different point of view and sees something completely different than the next person, and I’m so fascinated by that, so I just want the art to speak for itself and be open to interpretation.

MM: What was the inspiration for that artwork?

MG: Again, it’s fantasy, and when you see a setting like that, that’s so beautiful, what it makes you think of or remind you of or what you want to be there.

MM: What has inspired your work recently?

MG: I’ve been really inspired by interiors. Designing a room is art in itself; I’ve been looking to interior design and have been fascinated by it. When I look back at some of the most famous artists, like Matisse, and the way they painted the rooms, their studio — taking settings and adding impressionistic technique to make it come to life and have more movement. But still, my silhouette series has also been what I love doing.

MM: How did the pandemic change how you approached your artwork since you couldn’t travel, and did you find any creativity in that forced solitude?

MG: I find that I’m more inspired by the little things rather than going to these extravagant or beautiful settings that aren’t really real life, for the most part. But just because I’m in nature here I’ve been inspired by the smallest things — the way a tree is, or a movement in the water. •

All in-article images were provided by the artist Madeleine Gross. From top to bottom, “Miami Dream 2020”, “Two Lovers”, and “Poolside Muse”.