The history of modern art is strewn with the wreckage of obscenity charges. At the beginning of the 20th century, a work of literature with sexual content might initially be deemed obscene but eventually embraced for its esthetic and social importance. James Joyce’s Ulysses and D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover are notable examples. They opposed Victorian standards of propriety, but after passage through the courts and critical opinion, emerged as high art.

In the realm of cinematic representation, obscenity was initially an industry-wide concern. The Motion Picture Production Code was developed in the 1930s under the assumption that movies, as mass entertainment, needed to be monitored to protect public morality. Strict enforcement began to wane in the 1960s, and the Code was replaced by a more indulgent film rating system. Nonetheless, certain films struggled to maintain their integrity in the face of a dreaded X rating. Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Tango in Paris refused to amend its subject-matter to avoid such a rating, which reduced its box office profits. In time, however, it emerged as a film classic.

Television, too, began by monitoring its sexual content until the advent of cable TV did away with most forms of censorship. On premium channels at least, sex and art are now permitted to consort.

If there is one show that epitomizes the consummate expression of such intercourse it is the new STARZ series, The Girlfriend Experience. I should note that some critics have dismissed the show as mere stylish sexual exploitation. This criticism seems to forget how often art, as a taboo-breaking enterprise, has been labeled mere obscenity until vindicated at a later date.

The series is derived from a movie by the same name directed by Steven Soderbergh (who serves as executive producer on the series) and which gained notoriety primarily because it cast Sasha Grey, a genuine porn star, in its leading role. The film was original in its way, but as a film, it was limited in what it could do. By contrast, long-form narrative television, in following a character over an extended period of time, has added another dimension — what anthropologists might refer to as “thickness” — to what it is possible to represent. A further contribution to this “thickness” lies in the casting, not of a porn star, but of a third-generation celebrity, Riley Keough, Elvis Presley’s granddaughter, as the show’s protagonist.

The premise: a young woman named Christine (Riley Keough), a second year law student interning at a prestigious law firm, leads a double life, under the name of Chelsea, as a high-end escort.

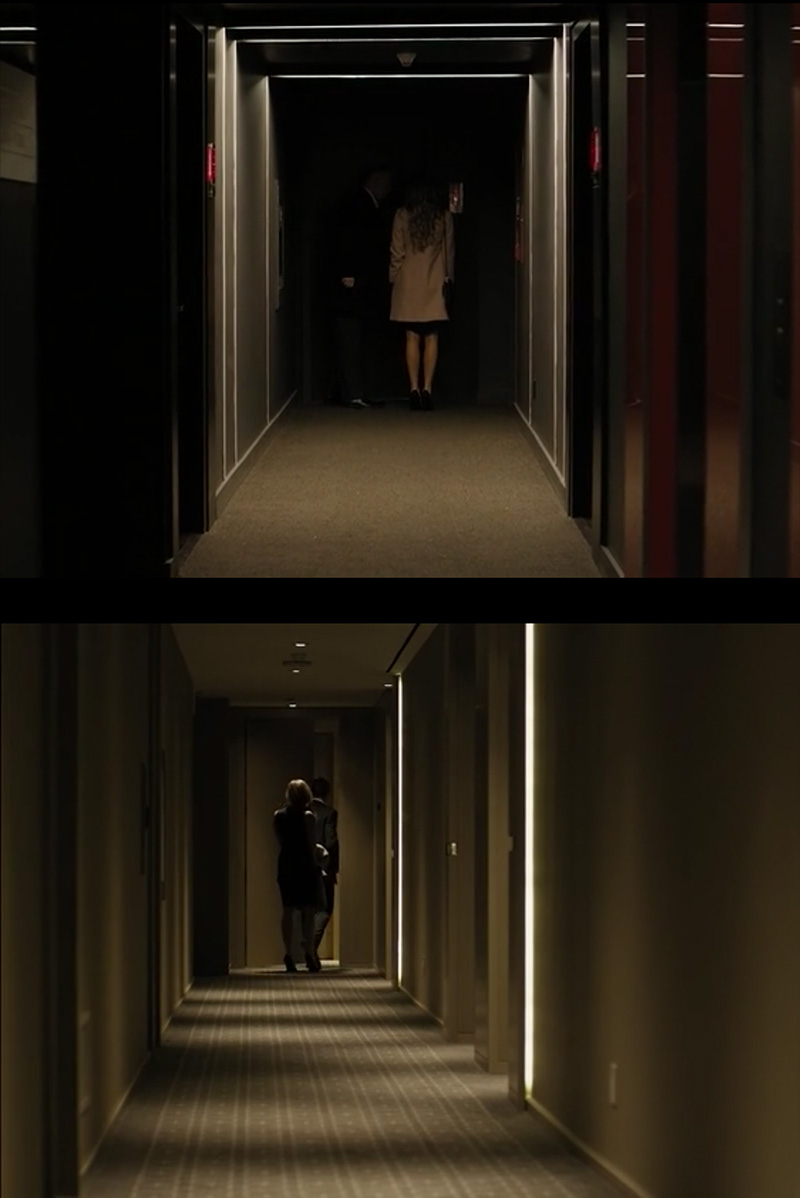

The production values of the show are exceptional but very much in keeping with pornographic conventions: the interiors are sleek and luxurious but impersonal; the protagonist is perfectly toned, with fabulous hair, chiseled features, and sexy underwear, as simple and elegant in dress and manner as the furniture. The plot involves regular intervals of fairly explicit nudity and sex, with all the requisite moaning and groaning. The show is only a half-hour in length, as if to underline, by its brevity, the centrality of the sexual encounters it represents.

But the series uses these conventions to relay many levels of meaning. In its focus on image and desire, it recalls Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, remade for the postmodern era. That movie inspired Laura Mulvey’s groundbreaking theoretical work “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Mulvey argued that cinematic representation – as epitomized by Hitchcock’s film – has been been traditionally directed at the male gaze; women are objects of that gaze, fashioned to serve as the locus of desire. Vertigo is about the self-conscious making of a woman, played by Kim Novak, in as the absolute embodiment of what the protagonist, played by James Stewart, desires.

Mulvey argued that the male gaze is so conditioned in culture that women as well as men are subject to its fascination, though women occupy the double role of being trained to see each other as objects while, at the same time, having to exist as such themselves. Kim Novak’s Judy thus tries desperately to be the artificial construct, Madeleine that he wants her to be. The Girlfriend Experience shifts this power dynamic: the woman now takes control of how she is perceived, and manipulates the gaze self-consciously to her own ends (her physical and monetary satisfaction).

This level of interpretation fits nicely with third-wave feminism that asserts the right of women to present themselves as they choose, even when this presentation seems to reflect unliberated femininity. We tend to think of the prostitute as a victim, who has been driven to the work out of financial necessity or psychological trauma. But Christine is a second-year law student with an internship at a prestigious firm. She possesses distinct and relatively rare assets that allow her to sell her body at a high price – and she happens to like sex. Her work as a call girl takes a kind of natural giftedness and expertise akin to that of being a successful lawyer. A motif in the show makes clear that the law firm at which she is employed is more manipulative and morally compromised than the sex trade in which Christine is involved (and where the exchange of money for service is more direct and honest).

But this interpretation of the show is incomplete. It doesn’t take into account the compulsive aspect of Christine’s behavior, the degree to which we are made to suspect that she is in thrall to something beyond herself — whether the shadow of patriarchal desire (her father?), or some form of self-destructiveness that compels her to this behavior. Her affect is listless and often robotic, except during sex, and she refuses to allow those closest to her to get a glimpse of an inner life. The result makes her seem like a beautiful automaton. This is no simple celebration of unencumbered female desire.

But if we try to settle for a pathological diagnosis of Christine, we then have to face the degree to which we may be subject to that diagnosis ourselves. To keep watching is to be doing at a remove what Christine is doing in the show. Much of the sex she engages in, moreover, occurs online. In keeping with this analogy, not only are the shows short and thus akin to the sexual encounters represented, but all 13 episodes of The Girlfriend Experience have been made available for viewing at once. To binge watch a show like this is to be immersed in its world, to engage in a kind of obsessive behavior akin to that of its protagonist.

The creators of The Girlfriend Experience have achieved something that entirely explodes the division between art and pornography, between a critique of patriarchy and an exploitation of it, between disgust and admiration, disdain and envy. The show gives sex-for-pay its a glamour and titillation that makes us identify with her at the same time that we anticipate that she will eventually self-destruct; i.e., be punished for what she is doing.

But the show is so sophisticated that we don’t know if our expectation of disaster is owing to the way life really works or to the conventions of representation that have to go this way to create the requisite drama and appease our own moral guilt.

We must end up asking: Why have we watched this show; what kind of people are hiring Christine and how are we like them; what kind of simulacrum is she of us? In short, where do we fit in this whole mesmerizing equation — not to mention, where did she buy her super-chic pencil skirts and silk blouses? •