When I was growing up in the late 1960s and early ‘70s, bad television was a redundancy. Think about what we had: The Beverly Hillbillies, Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In, Petticoat Junction, Get Smart, The Man From U.N.C.L.E. (even if Robert Vaughan did have a PhD). My parents, first generation intellectual snobs, were very down on television. I can remember my father looking up from his I.F. Stone’s Weekly and directing my sister and me, blissfully engrossed in The Man from U.N.C.L.E., to “shut that damn thing off!”

There had been a Golden Age of television once, early in the life of the medium, with shows like The Twilight Zone, Your Show of Shows, Studio One, and Playhouse 90. But by the late ’60s and ’70s, TV had abandoned its early promise and become, in the words of Newton Minow, FCC Chairman under John F. Kennedy, “a vast wasteland.” Then, in the 1980s, alongside such crappy fare as Three’s Company, Dynasty, and Miami Vice, there were stirrings of something better — Cheers, The Simpsons, and Seinfeld come to mind — and in the late ’90s and early aughts, a second Golden Age of TV seemed to emerge.

The watershed moment was the retrofitting of that age-old, low-brow TV genre, the soap opera, into a new and important form. The ur-specimen of this new and better long-form TV was The Sopranos, which debuted in 1999. Shows like Hill Street Blues and St. Elsewhere had begun moving in this direction as early as the early ’80s, but these better long-form shows were constrained by the conventions of network television. The Sopranos, by contrast, on a still nascent HBO, could push those conventional boundaries. It was followed by The Wire and Breaking Bad, each of which appropriated the form to different but equally idiosyncratic material and maintained the same high quality of writing and acting.

The new “good television” did not spring up out of nowhere. It had economic and technological roots. It was the result of the cable revolution, that unhooked the TV series from the immediate demands of advertisers, and gave it the freedom to use language and represent behavior, particularly of a sexual kind, that was not possible on network TV. Along with the changes afforded by cable was the consumer’s ability to tape shows in advance of watching, and, eventually, to stream and watch episodes in succession on different platforms (i.e. laptops, iPads, even iPhones). In the face of these innovations, creative people who had once been writing novels and long-form journalism now began writing for television. Minow, who in 1961 had observed that “when television is bad, nothing is worse,” might have been anticipating the turn to quality in the late 1990s when he also noted: “When [television] is good, nothing — not the theater, not the magazines or newspapers — nothing is better.”

Of course, the new good television was accompanied by a dark alter-ego in the form of trashy television — the deluge of reality programming that complemented the pricey long-form narratives in being cheap and narrative-less. But even trashy TV wasn’t exactly bad in the conventional sense in which, say, Gilligan’s Island was bad. Its mix of shamelessness and artifice, its use of ordinary people to do wild and crazy things, its insight into modern love, family dysfunction, and the vagaries of taste, gave it a novel fascination. Keeping up with the Kardashians and The Bachelor became windows into societal trends, and House Hunters and its spin-offs gave viewers a new take on how to live well through hardwood floors and granite countertops. Both good and trashy television were interesting and thus, in their respective ways, energizing of the medium.

But that was the recent past and, given that the media landscape can change much faster in the face of new technology, it is not so surprising that the current Golden Age may be winding down. There is an insidious trend afoot — a resurgence of “bad television” — that seems to be advancing on us at a rapid pace. I am not referring to the return of old-style bad network TV. On the contrary, new network shows like Blackish, The Good Place, and Jane the Virgin keep to the traditional network format of the sitcom or light drama but have appropriated elements from good, long-form TV.

But if good TV has had some influence over former bad TV, bad TV is creeping into long-form good TV. At least bad TV in the past made no bones about being anything but mindless crap. Petticoat Junction didn’t pretend to be War and Peace, and no one expected The Man from U.N.C.L.E. to give insight into the psyche of the angst-ridden spy (as such recent long-form TV shows as Homeland and The Americans do). Bad TV now has good production values, excellent actors, and a general air of quality and importance. This is what is insidious about it. I watched an example of what I mean recently, waiting for it to get good. Then, I realized that it wasn’t ever going to. What I took to be a prolonged set-up which would bring things together and clarify plot and character was simply all there was. In short, bad TV is good TV hollowed out and shamelessly exploited for its “aura” (a term that cultural theorist Walter Benjamin used to critique the commodified reverence that art has for a naïve public).

The show in question — which I think distills the badness that I see emerging across the cable landscape — is titled Succession. It deals with a tyrannical media mogul with a dysfunctional family who suffers a stroke, leaving his children to war among themselves over the leadership of his far-reaching empire. It’s on HBO, that purveyor of what we have come to think of as quality. The executive producer is the high-minded New York Times theater critic turned columnist now, apparently, turned TV producer, Frank Rich.

Succession has several elements that drew me to want to watch it. For one, there’s the enticing posed photo of the cast that appears on its promo page (a Vogue-ish pose that I realize is now becoming de rigueur — Mad Men and Billions both use such a shot of their casts for promotion). I was also taken by the haunting theme music and opening credits, suggestive of The Godfather crossed with Citizen Kane (I should note that the opening credit sequence has become an art form in itself — The Wire, House of Cards, and Game of Thrones have brilliant ones).

But as I began to watch Succession, I began to feel disoriented. Were the actors ad-libbing? Was the script written by someone who had never written one before? Was this a rush job to meet a deadline? The episodes, which began with great portentousness, soon came to seem like a collection of tics, gratuitous gestures, and unmotivated meltdowns. The evocative music, introduced in the credits and played at intervals throughout each episode, had no clear bearing on what was going on. The linking of character and plot — the idea, going back to the Greeks, that character is destiny — seemed to have been entirely forgotten. Even if this were an old-fashioned soap opera, more attention would have been paid to continuity. That this was a prestigious HBO production made the question of what was going on more confusing.

I have now seen four episodes of Succession and have an answer to this question that has implications beyond television. Here’s how I see it.

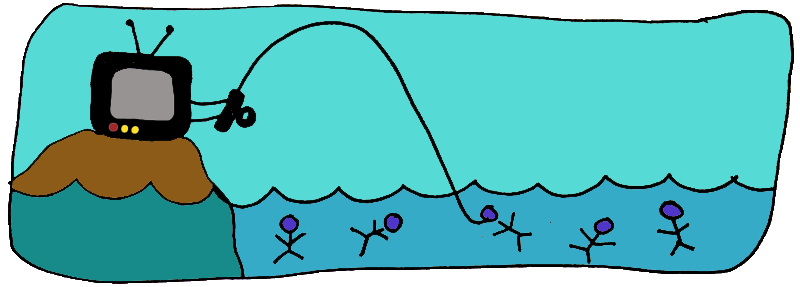

At the root of a show like this is the desperate need on the part of its producers to keep the viewer coming back. While cable initially seemed to be free from the pressures of ratings, the many cable channels and packages that have proliferated and the huge amount of programming currently being produced have given competition among shows a new and keener edge. Old TV created a viewership through repetition — each show was a self-contained unit and one returned out of loyalty to the characters and the known way in which they would behave. Think of Rob and Laura Petrie, the adorable suburbanites of The Dick Van Dyke Show; the charming bumbler Bob Newhart; the pedantic, neurotic Frasier. These characters comforted us with being so emphatically themselves. One of the funniest moments in Seinfeld occurred when George decided to do the opposite of what he would normally do, reinforcing, through reversal, who we knew him to be. The purest, if most uninteresting, example of this static aspect of network TV was the Mission Impossible series, where the characters were rigidly delineated and performed the same essential tasks with the same outcome from week to week.

But long-form TV is built out of episodes that are the opposite of static and self-contained; they spill into each other, with plot and character developing over time. This means that they must rely on suspense to carry the viewer forward. All good narrative has suspense, of course, but when the need for suspense becomes a pressing requirement for success, it can become dishonest and exploitative. An example occurs at the end of the second episode of Succession when the comatose patriarch, lying in the hospital, suddenly opens his eyes. We don’t have a sense of this man, except that he is a tyrant, and his sudden coming to consciousness doesn’t really have a point, since his behavior has been erratic up till now, as has that of the other characters. But the eye-opening seems to portend something very dramatic and illuminating. I therefore proceeded to watch the next episode with anticipation, only to learn nothing. The eye-opening simply created a jolt, but did not lead us toward a deeper understanding of the character or the situation. It was, in other words, a cheap trick.

In addition to the need in a show like this to supply end-of-episode suspense, there is also a more complicated need to create suspense on the level of character. This means leaving the delineation of character open for as long as possible, which is to say, indefinitely. If the eldest son, Kendall, is weak and incapable, this is helpful in creating moments of drama in which he behaves stupidly, others act meanly toward him, and he is profoundly humiliated. But because the writers are determined not to commit to his being weak and incapable, he is also given arbitrary moments of seeming strong and competent. Are we supposed to root for him as successor to his father or recognize that his leadership will be a disaster? Who knows? I certainly don’t think the writers do.

This kind of character vagueness operates for the other characters on the show as well. This includes the mogul’s wife, who is a cryptic figure — does she love her husband or is she darkly manipulative? And the other siblings who are presumably in a contest with each other for their father’s love and for control of his corporate empire but whom we can’t pin down as having any clear motivation. You may say that people are, in reality, changeable and mixed in their nature. True — but they nonetheless have recognizable character traits that give them a degree of coherence and continuity over time. But the characters in Succession are simply a string of surprising actions, gestures, and speech effects. One of the most egregious examples of what I can only call gestural exploitation is when the younger sibling, played by Kieran Culkin, is shown opening his pants and humping the massive glass window of his executive office overlooking Manhattan. What exactly is this unpalatable interlude supposed to illuminate? One imagines someone sitting around the writer’s table suggesting it as a suitably unnerving way to take up a portion of the hour.

I have used Succession as my example because it has recently begun to air and seems to reflect a larger trend that is penetrating long-form cable TV. Badness of the kind I have described is being inserted into good shows as they seek to prolong their life in a thicket of competitors. In the old days, this overreaching was known as “jumping the shark” — but now, given the freedom afforded cable, we could call it “humping the corner office window.”

Moreover, as binge-watching has become more popular, the cliffhanger ending of each episode and unmotivated, weird behavior on the part of characters have had to be exploited more aggressively in order to keep the viewer in a state of continual suspense. We saw this occur toward the end of Mad Men and House of Cards, the last likely to sink further into such contortions now that it has lost its ballast figure in Kevin Spacey’s Francis Underwood. Billions, a reasonably well-written show with strong central characters, inserted this kind of badness at the outset in having Chuck Rhoades, played by Paul Giamatti, be an S&M afficianado, a character quirk, one sensed, devised to get the series going with a bang (or rather, the lash of a whip). Interestingly, as the show proceeded strongly, it more or less dropped this element, only to reintroduce it more recently, when momentum began to falter.

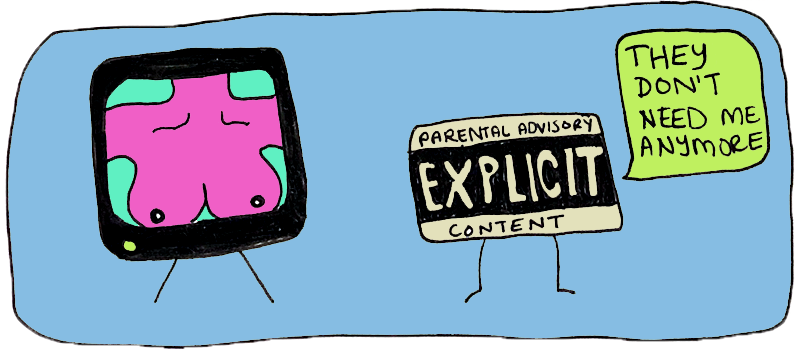

The irony is that long-form television initially was good because it didn’t need to stoop to such things. Yes, it could use foul language and show sexual material where network TV couldn’t. But overall, this raised rather than lowered the quality of the shows by making them more gritty, realistic, and free to explore uncharted territory. When a psychologically rounded character is placed in a situation that is allowed to unfurl at a natural pace and without the limits of censorship, the result is bound to be compelling. Characters can change over time in the long format, the way people actually do in life. This is what made good long-form TV better, in some respects, than good movies, which are confined to two-ish hours in their exploration of character.

What we are seeing now in bad long-form TV is reliance on gratuitous plot twists and character quirks. Someone good can become bad, then good again, based not on psychological logic but on the need to keep the viewer off-kilter and thereby engaged. Surprise becomes a commodity that eclipses the need for psychological logic. One could argue that reality TV, which is premised on the idea of surprise, has infected long-form television and brought it down to its level. But what in reality TV we accepted by virtue of its unabashedly superficial nature, we now accept even in productions that pretend to higher value and deeper meaning.

This leads me to the more disturbing observation that this tendency to rely on surprise as the method of keeping our attention is no longer confined to television. Indeed, I would argue that the new television, both long-form and reality TV, has conditioned us to expect certain kinds of entertainment from those around us. We have a president, himself a product of reality TV, who now appears to be the star of a bad long-form TV series. Like a character in Succession, he draws us to come back — to watch what he will do next and chatter about what he means (when in fact he means nothing but the desire to have good ratings). And like the supporting characters in current bad TV, all those who surround him, who might otherwise have prided themselves on having “good” character, have capitulated to his example. They accept his behavior in terms of the immediate gains that can be realized through it. Even those who oppose Trump are caught up in the endless effort to condemn what he has done or said. Surprise and shock are the engine for continual engagement. We forget that we should be attending to other things, that we are a country of laws and that principles of compassion, integrity, and opportunity for all should be of paramount concern. But such high-minded values do not have the kind of attention-grabbing power associated with dramatic overtures to dictators, obscene twitter messages, and sudden turn-arounds of policy and behavior. Melania Trump’s Zara jacket seems just the sort of thing that a showrunner for Succession would have dreamed up to intrigue viewers (perhaps never bothering to explain it — as no doubt we will never have it explained, though much ink will be spilt postulating on the subject).

This is a culture, then, of antic disposition — of ever-shifting and outrageous performance. Fred Allen, the radio personality, once said that “imitation is the sincerest form of television.” I fear that this amusing put-down of what was then a negligible medium has mutated into a more ominous form. Now, one could say, television is the sincerest form of politics — and of the reality that politicians make. •

All images by Isabella Akhtarshenas.