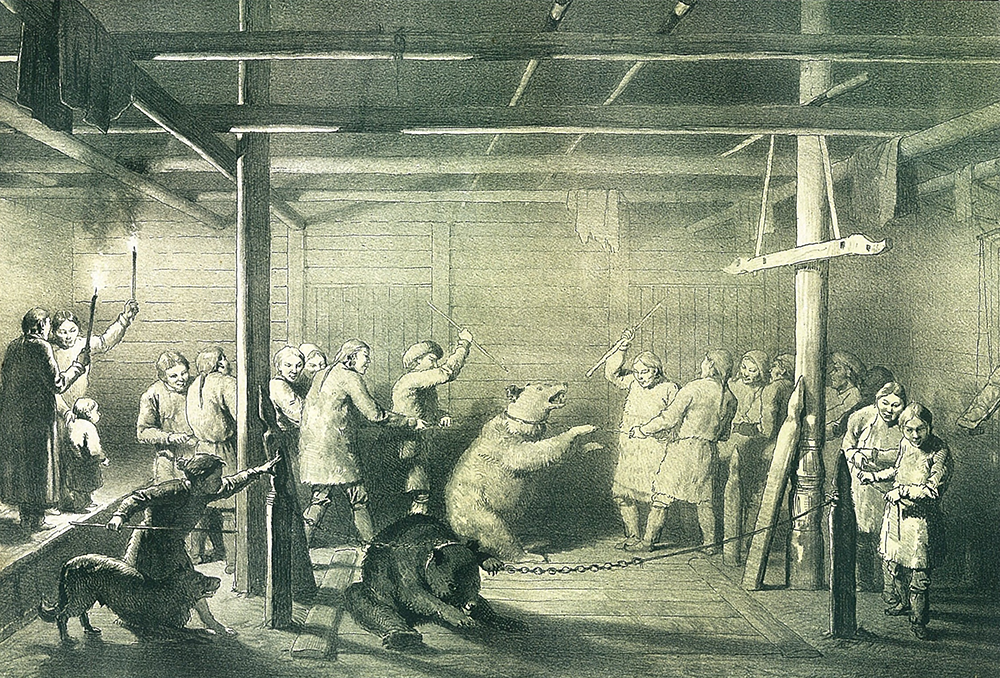

The moon was shining on the night in January 1856 when Leopold von Schrenck, a Russian-German zoologist, geographer, and ethnologist, reached Tebach, a village in the barren Amur region in easternmost Siberia. He was traveling in the name of the St. Petersburg Academy of Science, following in the footsteps of Alexander von Humboldt, who had made it all the way to the Chinese border. Von Schrenck is among the handful of Westerners who had the opportunity to participate in a bear festival with the Nivkh people (formerly called Gilyak). As he approached the village, the inhabitants were out and about. The women stood in front of the houses carrying babies and watched as the men and the older children held hands and spun rapidly in a circle. Once the dance was over, von Schrenck accompanied the group into a yurt — a kind of oversized tent. Three bears were bound to the two central support poles. Care had been taken to allow the bears room to lie down, stand up, and move from side to side. The visitor also had to take care “not to be struck by a bear’s paw.”

Finally the bears were untied and led from house to house. This entertainment lasted for several days, occasionally interrupted by dog races, drumming by the women, and games.

At the same time, the place where the bears would meet their deaths was already being prepared. Out in the open, a long rectangle was marked with poles and two posts were rammed into the ground. On the evening beforehand, the bears were led onto the frozen surface of the river:

It was a long train that set off to the stream, since besides the three bears, which were led in the same order as always, a number of unoccupied boys followed. As the bank is high and descends quite steeply to the river, it was interesting to see how the train moved down the slippery slope without becoming disordered, even for a moment. While those holding the forward rope ran down, those at the rear had to hold back with all their might to prevent the bear from rushing down just as quickly and causing damage. With their combined strength, they managed to bring all three bears to slide slowly and steadily down the slope.

Throughout the night, the men fed the bears and the women prepared dishes for the next day’s feast. In the morning, the bears were led once again to the river and taken to the spot where they were to be sacrificed. There the village boys shot at them with arrows; the bears’ owner decided which of them should deliver the death blow. The bears were then dragged into one of the houses and butchered. The villagers ate the meat and fat throughout the remaining weeks of the festival, but the three heads and the skins were hung on a beam across from the yurt.

On one of the following days, bands depicting toads were tied around the bears’ snouts in order to “dry the tears welling from their eyes,” as von Schrenck reports. The Nivkh considered toads to be evil spirits and held them ultimately responsible for the fact that the bears had been captured, killed, and eaten. A second band made of agate beads from China was then tied crosswise on the bears’ heads. Von Schrenck saw a parallel between the placement of the beads on the bears’ foreheads and the raised areas on the foreheads of certain Buddhist deities.

The scientist claimed that the festival was “partly motivated by the desire to honor a powerful predator and partly by superstitious fear of him and his revenging spirits. He is granted the place of honor in the house and the impression is created that the participants act both with his permission and against their will. In the end, they deflect all guilt and responsibility from themselves.” As detailed as the account that von Schrenck delivered about the rite seems, the Nivkh may have kept some aspects about their relationship to the bears to themselves, since we don’t know how accurate the communication between him and the natives really was.

Von Schrenck proved to have a remarkable capacity for empathy: he tried his best to understand what he had witnessed in this inhospitable region. Former travelers and clergymen who were aware of the “dark magic” practices of tribes in Northern countries, such as Swedish missionaries, were repulsed yet somewhat fascinated by these procedures. The practices were fought and the cult objects destroyed. In his book A Description of the Northern Peoples, dating from 1555, the Bishop of Uppsala, Olaus Magnus, mentioned the “terrible idolatry and Devil worship that northern people practice.”

“The practice of bear cults is widely spread among numerous circumpolar hunter clans, including the Yakut and Chukchi people,” explains Liane Giemsch, who has curated a groundbreaking exhibition of various artifacts pertaining to these cultural traditions at the Archaeological Museum in Frankfurt, Germany. In wider Siberia and Scandinavia, hunted animals were not only objects of cult worship by countless indigenous peoples during the last century but were also embedded into complex rituals. Northern Eurasian hunter clans believed that spirits populated their environment and that hunted animals were kindred souls. Shamans, who often ate toadstools known for their hallucinogenic properties, accompanied entire rituals and acted as mediums between the worlds. In a state of ecstasy, they supposedly ensured cosmic balance on the journey to the next world. Here we can see features of a “primary” human religion, whose roots lay in the hunter-gatherer and fisher civilizations of prehistoric times.

The cult of bears and horned beasts can even be traced back to the Paleolithic Age some 40,000 years ago. Clues to these kinds of cultish practices can already be found in numerous Paleolithic caves. Models of miniature cave bears made of mammoth fur and bears’ teeth drilled with holes were probably used as burial objects and still present many puzzles to this day. Archeologists are at odds over the details and form of Paleolithic “cave bear cults” and the extent to which they resemble more recent rituals.

There is no doubt, however, that bears occupied a prominent and unique place in early cultures and had a special relationship to humans. These assumptions already formed the cornerstone of Bear Ceremonialism in the Northern Hemisphere, a study that the American cultural anthropologist Irving Hallowell published in 1926. Although the festivals celebrated by both Eurasian peoples and many Native American tribes varied from region to region, Hallowell found that the bear was honored as the lord of the forest or the son of the supreme ruler: it was seen as an alter ego that could take on human shape and be identified as human. Groups widely scattered across vast geographical distances, Hallowell claimed, shared for example the belief that a bear killed in the hunt would enter a new life.

From today’s enlightened perspective, rituals such as those depicted by von Schrenck seem alien and cruel. How should we comprehend them? “What’s important is an understanding for the reality and worldview of these peoples. Hunter and gatherer tribes felt themselves to be part of nature and thought that they interfered with its balance by hunting. Through an awareness of their dependence on hunted animals’ reproduction, these people created cults and rituals with which they tried to ensure their livelihood. Following this insight, it is the main task of these rituals to uphold harmony with nature,” explains the curator.

Complex bear-hunting and killing ceremonies disappeared under the pressure of modernization, but were observed in isolated regions into the 20th century. One example is the spectacular photographic documentation of a bear festival among the Nivkh people in around 1934, which arrived in Germany via Chuner Michaelovich Taksami, the director of the Russian Museum of Ethnography in St. Petersburg. The series of photos, which bears witness to many aspects of von Schrenck’s description above, is considered the last surviving document of this ritual. The highlight of this festival was a so-called “house bear,” which would be captured in spring as a cub, after which it was considered a full-fledged member of the family. The end of the ritual would see the arrival of an archer who would shoot the exhausted bear. If the animal was still alive after three arrows, the next archer would take his place. The man who skinned the bear would deflect all guilt. The bear would then be eaten.

Not much is known today about the Nivkh people’s fate and ideology. According to one estimate, there are still some 5,000 members of this tribe, who were already oppressed during the Tsarist empire. Later, during Soviet times, religious practices were strictly regulated by the government, including shamanism and bear ceremonies. The disappearance of such cults is therefore inextricably linked to the Soviet regime.

The merit of this exhibition consists in having brought into a continuum surmised cave bear cults and shamanistic bear rituals. These are illustrated in the exhibition with the help of true-to-original reenactments and fascinating visual records. Furthermore, a complete shaman costume painted red, numerous totem figures, and a rare surviving shaman’s drum are on display. Bears’ graves from Sweden and Norway can also be seen alongside various artifacts from cave bear cults and the reconstruction of a bear’s body molded from clay taken from the Montespan cave in France and estimated to be 80,000 years old.

The special exhibition “Bearcult and the Magic of the Shamans: The Rituals of Early Hunters” can be seen until March 2016 in the Archaeological Museum of Frankfurt. •