Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942) is known, if known at all, as a quiet, conservative painter — a portraitist of the wealthy and well connected in late 19th- and early 20th-century America. Neglected for most of the last century, she has received a modicum of recognition in recent years, with a number of monographs and a comprehensive exhibition of her work in 2007-2008. Contemporary critics have characterized her, much as those of her own day did, as a very good painter, technically proficient, and dedicated to her art.

But this assessment doesn’t begin to do her justice. It seems time for Beaux to be viewed afresh, not just revived. For she is more than a conventional realist, more than a realist with Impressionist tendencies, more even than a portraitist. She is, I would argue, a great original, for whom labels of school, method, and genre fall short. She deserves comparison with her great predecessor, Édouard Manet. Manet was brash and revolutionary; Beaux, restrained and insinuating — but she repays attention with insights as profound.

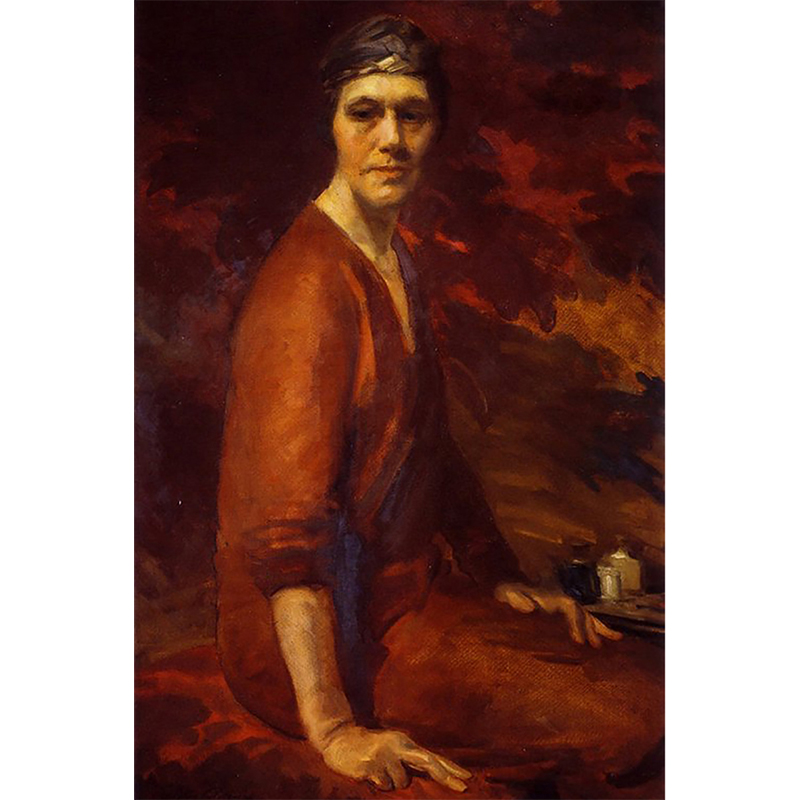

Cecilia Beaux was acclaimed in her lifetime. She won major prizes, exhibited regularly in the Paris Salons, was asked to contribute her self-portrait to the Uffizi, and was praised by the celebrated artist and critical arbiter William Merritt Chase as “not only the greatest living woman painter, but the best that has ever lived.” Still, her reputation existed within defined parameters — she was always seen as a traditionalist, a portraitist, and, of course, a woman.

In longevity of reputation, Mary Cassatt, also American by birth, has overshadowed Beaux, having maintained a closer association with the progressive male painters of the day. Beaux traveled abroad in 1888 and did the de rigueur study in Paris, but, unlike Cassatt, stayed only 19 months. Her career was spent in Philadelphia, New York, and Massachusetts, and her circle was relatively small and elite. She was not of the people and did not wander too far afield, literally or metaphorically, for her subjects.

Beaux was also, unlike Cassatt, interested in capturing likenesses more than — or in conjunction with — relaying “impressions.” In this, she is most often compared to another contemporary, John Singer Sargent, who took pains to portray his subjects as individuals. Sargent, though more flamboyant and facile in his style, also concentrated on painting a socially connected group of which he had a place — though his circle was wider and more cosmopolitan. (Sargent was labeled an American painter by virtue of his parents’ nationality, but he was born and spent the majority of his life in Europe.)

When portraiture began to go out of vogue with the advent of Modernism early in the 20th century, the reputations of both Sargent and Beaux declined. Sargent has made a definitive comeback in the last 20 years; Beaux has less dramatically followed suit. Yet, this renewed attention to her work, modest though it may be, has provided an occasion to assess her apart from her time and her contemporaries.

What springs into relief on looking closely at Beaux’s art in the present context is how much she managed to remain aloof from the major movements and influences of her day. This independence, which once made her look provincial, can now be seen as an expression of integrity and originality. Beaux notes in her autobiography, Background with Figures (1930), that she made a concerted effort to avoid the spell of Thomas Eakins, the much-acclaimed artist and teacher at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, when she began her career in Philadelphia: “I was out of reach of the obsession of his personality, which I would have been sure to succumb to, and this might have resulted in my being a poor imitation of what was in some ways deeply alien to my nature. A curious instinct of self-preservation kept me outside the magic circle.” During her time abroad, she was content to work with lesser instructors in L’Atelier De Julien, a school not associated with any one artistic personality. She had no interest in studying with the celebrated Carolus-Duran, in whose studio Sargent apprenticed. “I shrank,” she wrote, “from the committal [to an individual master].”

Beaux’s refusal to commit herself to a singular influence or school makes her hard to categorize. She was not a domestic genre painter of the Impressionist mode like Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, not a stern and sober realist like Eakins, not a painter of silk and pearls like Sargent. After studying in France, she incorporated impressionistic elements into her work but never embraced a stylistic method, whether Impressionist or Modernist, in any consistent way. She was known as a portrait painter, but looking at her so-called portraits today makes one amend this nomenclature, too. While she painted people almost exclusively, one rarely gets the sense of a patron shadowing the work — unlike Sargent, who flattered his subjects with extra inches and more chiseled features, and took pains to represent their status through opulent clothes. (The stress of painting under commission is what eventually caused Sargent to swear off “paughtraits,” as he called them.)

Beaux was, in fact, less a conventional portraitist and more a painter of people she knew intimately — familiarity easing the need to please. Her best canvases feature two figures: mother and child, sister and sister (or brother), husband and wife. These paintings depict an implicit narrative of close, if emotionally fraught, relationships that make them compelling in a way that may be unique in the history of art.

In trying to grasp the originality of Beaux’s “relationship paintings,” I want to cite a passage in her autobiography that seems a helpful adjunct to understanding them. The autobiography focuses, almost exclusively, on the development of its author’s artistic career and aesthetic vision. One learns next to nothing about her life apart from her art. Yet, there is one significant deviation early in the narrative when she discusses a period in her 20s before her career had gotten underway in earnest. The passage is interesting both for its contrast to everything else in the book (it seems deliberately bracketed off from the rest of the narrative and expressed in a rather cryptic style) and for the way in which it can help illuminate Beaux’s art:

. . . as I stumbled through the rough country of these years, there were dark mystifying nights, too bright dawns, and puzzled searchings for the path. As was natural, I was not much alone. It was the time for love, and the little god was pretty constantly about. I got my work done, but there was not much time for meditation on the status or real value of it. Other things had to be decided. It was a thorny path, for in these matters it, unfortunately, frequently happens that youth is temperamentally indisposed toward the exceptionally eligible (who may be also categorically attractive) and drawn toward those whom it would never be finally conquered by. There was plenty of agony and some clear-cut drama, in a setting of November days, fresh and clearing skies, and the odor of violets the sad heart offered. There was always the terrible standard of what love should be that held back the romantic heart . . .

In the mean time, I watched my sister float away on the happiest of marriage destinies, without a ripple to mar its certainty or one backward glance . . . Happy is she, I thought. Shall I ever come to it? I was by no means set against marriage and had no glimmering vision of another sort of future I might have. Let escape this period, without further comment. The time came when the next allowed opening was ready for me, and I for it. [Italics mine.]

This poignant description of unrequited love — of being unable to “conquer” those whom she was “drawn to” — seems connected to Beaux’s childhood experience. Her mother died soon after her birth, and this so affected her father that he placed Cecilia and her older sister Etta in the care of their maternal grandmother and returned to his native Belgium to recover. He would come back to his family and leave again a number of times until his death in 1884. Beaux writes affectionately but sparingly about her father in her autobiography. As the passage above suggests, after experiencing disappointment in love, she went on to devote herself single-mindedly to her artistic career and, unlike her sister, never married or had children.

The logic that links the abandonment of the father to the subsequent inability of the daughter to love anyone capable of loving her back is simple enough. But that linkage becomes more interesting when we look closely at Beaux’s best paintings. These works, in which two related figures are posed together, are both emotionally intense and profoundly analytical. Indeed, I would argue that the pain of having been rejected by her father and subsequent lover(s), combined with her outsider status with respect to marriage and motherhood, gave Beaux the tools to paint with feeling and detachment — to reveal the mechanism of a particular relationship between people and, at the same time, to offer a broader cultural critique of that relationship. The four paintings I will discuss below illustrate what I mean in varying contexts.

The first is titled Les Derniers Jours d’Enfance, painted in 1885, a year after her father’s death, when Beaux was barely 30 years old. What must strike the viewer at once is how accomplished this work is, especially given the inexperience of the artist. Beaux had only modest formal training at this point and had never before done a large-scale oil painting. She had worked mostly in other media — painting plates and doing scientific illustration — to help support her family. Only with the decision to paint this work did she come to see herself, for the first time, as a genuine artist. Or, perhaps, it was the other way around: the decision to be an artist fed her confidence to paint such an ambitious picture.

The idea of being a “professional” painter of pictures seems to have occurred in a leap — that “next allowed opening” referred to in her autobiography. It was as though she had crossed over from being an ordinary girl, who like her sister, might marry, to being someone different, who would dedicate herself entirely to art. Like this new vision of vocation, the idea for Les Derniers Jours d’Enfance also sprang, as she recounts it, fully formed into her head, even to the title, which she knew had to be in French — possibly to underline the foreign territory about to open, not only to the mother and son represented in the painting but also to the artist depicting them.

Beaux knew not only what she wanted to paint in Les Derniers Jours d’Enfance but also what she needed to paint it. She went about methodically finding a studio space in downtown Philadelphia and then staging the scene she had in mind: choosing the clothes of the sitters and the background props and decor she wanted. The work that resulted has the gravitas of an Old Master painting while also showing the influence of more contemporary painters: James Whistler’s portrait of his mother, most notably, but also Manet’s Olympia, not only in its generous use of black paint but in certain stylistic elements in the poses, despite the dramatic difference in subject-matter.

But if the work seems to invoke various, antecedent influences, the emotional narrative it depicts seems entirely its own. The feeling relayed by the painting is somber and increasingly intense, the more one contemplates it. Most notable on first viewing is the quality of dreaminess of the subjects, a characteristic of many of Beaux’s subjects, particularly her women. Here both mother and son project it, though the mother’s face is more mysteriously remote. Since her eyes are lowered, one cannot tell if she is dreamily looking down at her child, daydreaming to herself, or asleep and actually dreaming. The boy is also dreamy, though here the quality is projected outward rather than inward. He seems to be drifting away from the mother who holds him in her lap, dreaming perhaps about his prospective life in the world.

The focal point of the picture, as Beaux explained when she wrote about it, is the hands: the mother’s are crossed over the boy’s lower waist, his resting lightly over hers. She is gently holding him in place, and he is vaguely, but perhaps only momentarily, acquiescing. The dark paneling of the room, the mother’s black dress, the shadows on her face, and the child’s little strapped black shoes — all seem like background from which the boy’s body, in its white striped sailor outfit, sprawled white legs, and pink-toned face have been “placed,” both for the aesthetic purpose of the painting, and, more dynamically, in order to dramatize their imminent detachment from the background. The busy-ness of the child’s costume as it contrasts the simplicity of the mother’s dress suggests that one is static, the other active — one will stay, the other leave. With only the boy’s shoes blending into the skirt of the mother’s dress, one almost feels that this — and the light touch of the child’s hands over his mother’s — are what connect the two figures.

It is a poignant portrait of the mother’s imminent obsolescence — what I take is inspired by a combination of Beaux’s experience with her father and romantic relationships in general as she described, and her desire, perhaps unconsciously, to rationalize her decision not to marry and have children.

The second painting that seems to brilliantly reflect Beaux’s unique way of seeing was completed two years later. Harold and Mildred Colton depicts a brother and sister in a family the Beauxs knew so well.

The siblings in this painting are seated together on a corner-configured chair, the boy, much as in Les Derniers Jours, facing forward; the girl in three-quarter view, though turned in the opposite direction from the mother in the earlier painting. Beaux has posed the children with allegorical objects denoting their gender: Harold is holding a riding crop, Mildred, an apple. The picture is mesmerizing — sumptuous and unsettling at the same time. The boy seems knowing beyond his years; the girl, similarly self-contained, though less direct in her gaze. I am not the first to be put in mind of the two children in Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, written a year afterward: perfect little angels in their superficial demeanor whose governess becomes convinced that they are possessed by demonic spirits. The more one looks at the picture, the more the girl’s face, along with her little hand grasping the apple, conveys knowingness laced with anxiety; while the boy, with his crop and steady gaze, seems aggressive, even threatening. As sharply depicted as both faces are, there is that element of dreaminess — of being solidly placed in reality while wandering in imagination elsewhere. The gender contrast also seems central here, but more complicated than the one depicted in Les Derniers Jours. Is the brother his sister’s protector or her nemesis? Is Beaux recording the different destinies that lie in store for these two as a function of their gender? The more one looks at the picture, the more the boy seems ready to spring forward, while the girl’s little green-sleeved arm appears, by some unconscious or reflexive impulse, to be holding him back. Surely, there are few portraits of children that incorporated so powerfully both the inchoate mystery of childhood and the sense of the fully formed adults they are destined to become.

The picture Mr. and Mrs. Anson Phelps Stokes (below, right), was painted ten years later in 1898.

This painting was clearly influenced by a famous painting by Sargent, Mr. and Mrs. I.N. Phelps Stokes (above, left) completed the year before, of the son and daughter-in-law of the couple in Beaux’s dual portrait. In Sargent’s painting, the daughter is in riding dress with her husband standing in the shadows behind her. Sargent had presumably first painted a large dog where the husband now stands, a fact that helps reinforce the sense of reverse-gender hierarchy the painting amusingly suggests. Whether this is an accurate depiction of the young couple’s marital relationship is unclear, however. The husband in the shadows could just as well be an ominous figure as a negligible one — a Gilbert Osmond who has clipped the wings of his trophy wife, Isabel Archer, to draw on Henry James again and make an analogy to The Portrait of a Lady.

In Beaux’s painting, which is far more subdued and subtle than Sargent’s, the sense of the couple’s relationship comes through more clearly, if not more simply. The elder Mrs. Stokes is, like the younger in Sargent’s painting, in the foreground. She is smiling slightly but looks vaguely fatigued and remote. Represented in all the trappings of affluent middle age, she is a slightly corpulent figure in an ultra-feminine dress of purple flowers, stripes, and lace. She holds her pen lackadaisically amid a scattering of papers. Behind her, her husband sits, a somewhat blurred but slim and dignified figure, holding a newspaper. The sense is of a couple caught in a familiar pose. But the dreamy remoteness of the woman’s expression suggests that she might be imagining another life from the one she has.

It is not a mean picture by any means and not a humorous one — where Sargent’s of the younger couple could be accused of being both. One can see why Beaux’s subjects liked it. But it has a whiff of sadness — a sense of possibly unconscious disappointment, unfulfillment, and repression, not just in the woman but in the man, whose unfocused forward gaze and red cravat suggest a more adventurous life unlived. Again, one must look at the picture for a while to fully appreciate what Beaux is suggesting, taking note of the unusually frilly and flowered dress, the hands amid the papers, and the stiffly formal husband behind. There is empathy but also a judgment of the idleness associated with the lives depicted here. There is also, I would suggest, a tinge of jealousy on the part of the artist with regard to a life so lush, protected, and conventional. All of these things seem to be present in the work and make for a richer psychological depiction than Sargent’s, wonderful as it is.

The final picture that, for me, encapsulates Beaux’s unique vision is her 1902 Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt and Daughter Ethel, painted four years after the Stokes portrait and 16 years after Les Derniers Jours d’Enfance. Beaux met President Roosevelt and his family through her friends, the Gilders, who circulated in the highest reaches of American society and introduced her to many influential people. (Beaux also did a small portrait of Theodore Roosevelt during this period.) Her picture of Mrs. Roosevelt and her young daughter is, to my mind, the most dramatic study of all the works she did for the mother-child relationship. It bears comparison to Les Derniers Jours d’Enfance but differs in style and emotional tone. The difference lies not only in the span of years that separate the two works and the subjects involved (the first from her own family; the other, from the nation’s family) but in the fact that the gender of the child is different: a daughter rather than a son. This shift seems central to the emotional vibe of the picture.

Mrs. Roosevelt is in the foreground in a white ruffled dress, set low on the shoulders, with a light blue bow at the front and a gold necklace around her neck. She is in almost complete profile, an elegant figure, smiling slightly, though with that vaguely attenuated air that was also discernible in Mrs. Stokes — the remoteness, in other words, that characterizes women in so many of Beaux’s pictures. Seated next to and slightly behind her is Mrs. Roosevelt’s daughter Ethel in a white sailor suit, not unlike the outfit that Beaux’s nephew wore in Les Derniers Jours. She is looking straight at us, and her face is the most striking element in the painting. It seems to be aquiver with life: blotchily represented with red and white brushstrokes for cheeks, chin, and lips.

In the face of the child, one sees the influence of the Impressionists, whose work Beaux was exposed to during her Paris visit a few years before. Here, however, the method is used, less as a style for the painting as a whole, than as a means of representing her subject’s particular state of emotion. The girl’s face is in marked contrast to the placid profile of her mother, whose expression is set, well-controlled, and more realistically painted.

As in Les Derniers Jours D’Enfance, the child has her hand on top of her mother’s, though in this case the hands are entwined, as though the young girl were holding onto her mother, anxious about where letting go might lead. The child’s face registers this related mix of anxiety and excitement. The painting seems a study in the maternal role as it relates particularly to the female child: its function of damping down the erupting emotionality, curiosity, and engagement of the daughter. The daughter is experiencing feeling; the mother is repressing it, in herself and in her daughter, and the daughter is succumbing while displaying the difficulty of doing so. Again, it should be noted that the Roosevelts liked this portrait. No doubt the message that I discern in it would be seen at the time as a proper one. Yet coming from Beaux, a professional woman without children, it also becomes a subtle critique of the mother-child relationship as dictated by the society of the period.

This sense of the tensions and ambiguities of lived relationship is what, to my mind, so distinguishes Beaux’s art from Sargent’s. Although he often painted two or more people in his portraits, the idea of relationship predominates over the sense of a lived interaction. This is evident in his portrait of the young Stokes couple and, even more, in his famous Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, which shows four sisters, each at a different point in her childhood, posed so as to evoke the mysterious passage from childhood into adulthood. The daughters exist both as individuals and as the expression of this idea, but not in real relationship to each other.

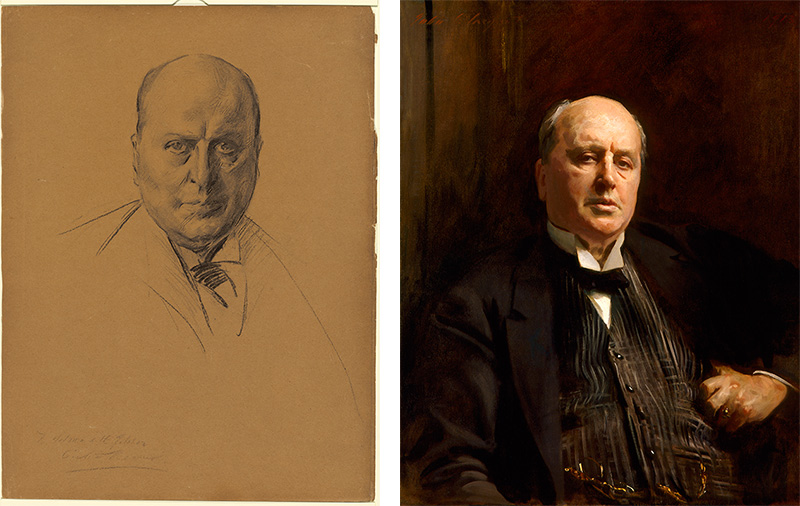

The relational aspect of Beaux’s art becomes more evident when we compare her portraits of paired figures to her portraits of individuals alone. A noteworthy example is her sketch of Henry James, a writer whose work I have invoked as sharing certain elements, albeit in a literary context, with her. Nine years after painting the portrait of Mrs. Roosevelt and her daughter, she was introduced by the Gilders to James and completed the charcoal sketch of his head (below, left). This must be the most ominous image ever done of the novelist — a marked contrast to the delightful oil portrait by Sargent of around the same period (below, right). James, with typical obliqueness, noted that it reflected a “wonderful economy of means.”

One wonders whether Beaux was intimidated by James or resentful of him. The sketch looks like a death’s head. It might well be connected to her belief that the influence of great men was to be avoided — that they could “swallow her up.” James certainly looks like he could do that in her sketch.

After World War I, Beaux was commissioned to do portraits of three major figures important in the European war effort: Cardinal Mercier, Georges Clemenceau, and Admiral Lord Beatty. She waxed on about her admiration for these men in her autobiography, and the portraits that result, unsurprisingly, represent them as impressive, regal figures. As such, however, they also seem flat and iconic. They have none of the complex psychological resonance of her best paintings, which feature an intimate relationship between two people.

It would be far too simplistic to say that Cecilia Beaux’s was a feminist vision. In many ways, she was a profoundly conventional person, despite the unconventional choices she made in the way she led her life. What her best paintings do show is a modern vision — with a small “m.” They relay the fears, jealousies, and identifications that occur between people. They also relay a deep understanding of the costs of intimacy. These are emotions and psychological states that one feels Beaux knew through her experience with her own family of origin but chose or was forced to suppress in order to be an independent artist. Her work encodes gender into that depiction as it contributed to how women, in particular, were expected to behave and be perceived during the period in which she lived. But the paintings seem less a critique of women’s role as an exploration of the bonds and costs of relationship — the confining but emotionally intense position that many women embrace, the loneliness and perspective afforded the artist, and the fraught nature of the human condition more generally. •

Feature image by Emily Anderson. All others courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the National Portrait Galleries in Washington D.C. and London, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, and Wikimedia Commons.