This essay contains derogatory language that has been included to articulate the abuse experienced by some canvassers.

You’re cold. Shivering. Your legs pump back and forth, trying in vain to generate heat. Your feet are cracked and aching, fingers turning to steel. You can feel your breath leave your body as you wait, exhaling plumes of cigarette smoke without actually smoking though in all likelihood you’ve already gone through a few and it’s only about 7 p.m. Three hours pass, two more to go. You’re standing at a stranger’s door, having just rung the doorbell twice. You jiggle your clipboard in anticipation. You are wearing an official T-shirt in an odd color underneath a thin neon blue jacket with a large logo affixed to the front and back. You feel vaguely ridiculous and very much alone.

There’s a small tinge of hope mixed in, however. You’ve seen whole nights of hard labor redeemed in a minute and a half. You’ve also gone home hungry, beggin’ cup empty, to take the long subway ride back to the office feeling more than a little like a younger version of Willy Loman. You’ve currently got 65 dollars in checks and small bills in your pocket, but your daily quota is 120. You were behind quota yesterday, and the day before, but three days ago you raised 200 dollars — a great night, a splendid night, a “hot night!” You need to be at quota for the week. You really need to be at quota for the week.

Whoever lives here has a nice house, large and stately, though not overly ostentatious. Someone raises a family here. If the garage wasn’t closed, you’d give the car a quick appraisal. Through the window, you can see the warm lamplight humming over bookcases and a stereo. It looks promising; luminous, warm, almost inviting. You hear the sounds that dinner makes. You’ve come to know well the small roar and crackle of highway cars echoing in the distance. You feel a little bit like an actor auditioning for the same role, in the same play, for the 13th time in a row.

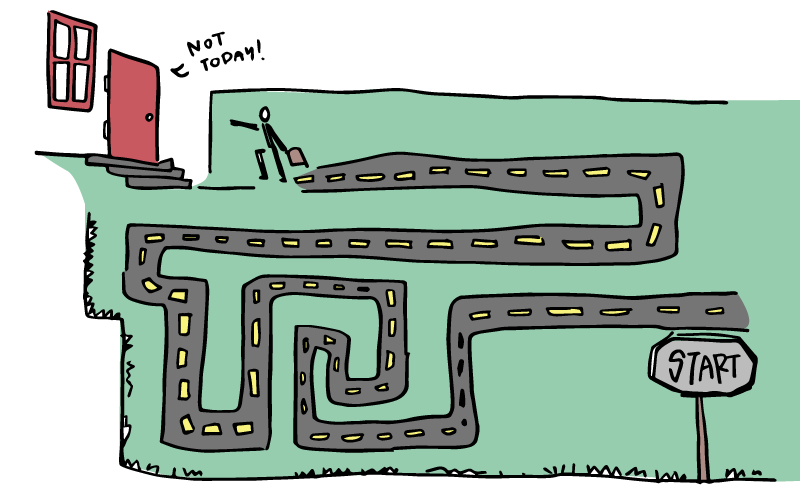

It’s a nice neighborhood. These four or five streets, chosen almost at random, are your turf for the night. You’ll most likely knock on 100 doors, talk to around a dozen people, and maybe five or six of these people will give you money if you’re lucky. You’ve never been here before and you will most likely never return, but this series of streets will subtly become a microcosm of the world until quitting time. The location is decided from a general aggregate of voter data. There is, contrary to public suspicion, little interest in targeting specific persons. Not everyone is friendly, not everyone is on-board with the cause. Not very many people are glad to see you.

You have what you might call an interesting job. You meet more people in a day (even superficially) than most people do in a month. You shake hands, you goof with children, you look strangers in the eyes and talk directly into them. You catch glimpses of fascinating (and probably fictitious) backstories in a sideways glance or a casual gesture. You are often privy to the facts of a real person’s real-life: you learn about their family, spouse, income, livelihood, opinions, politics. And this happens in different ways with the dozen or so faces you greet every night. You have met all manner of fellow citizenry, all races, colors, and creeds: middle-aged Portuguese men who live with their mothers, edgy Black urban youths, octogenarian and indestructible Jewish grandmas, ancient Irish union men, embarrassingly friendly Albanian couples, Latina housewives, Russian 20-somethings who followed their boyfriends from Moscow to the States. Self- described relatives of Lord Byron and Winston Churchill. You meet upstart yuppies with popped collars and spiked hair, hippies, church folk, screw-ups, rednecks, soldiers, students, carpenters, cops, millionaires, judges, poets, deadbeats, doctors, lawyers, bartenders, and some of the loveliest fellow citizens you have ever laid your eyes on. You flirt, sometimes. You fall in love at least once a day.

Make no mistake about it — the work is physical. You tiptoe down icy stairways, clamber through mazes of steeply winding streets, grunt your way up 20-foot-high porches, stumble up hills, stumble down hills, walking everywhere all the time. You sweat, you lose weight, you’re profoundly glad to sit down at the end of the day. Your boss has been known to wrap her feet in plastic bags, under the shoe, during snowstorms (and yes, you do canvas in snowstorms). You exhaust yourself. You have the distinct pride of really having earned your paycheck, savored the little bit it brings, since what it essentially amounts to is a pile of shekels in your beggin’ cup, even if the money isn’t intended for you. This is enhanced by the fact that the amount of said shekels fluctuates without mercy. You do, after all, walk alone at night for hours, convincing complete strangers to give you money.

It can be tough. It can be unbelievably tough, and in ways, you could never have imagined and that only fellow canvassers can really understand. People, quite simply, can be assholes. You know this from consistent exposure. You will never forget the lessons it teaches you. Samuel Johnson once said that you can tell a person’s character by how they treat their social inferiors and you know the truth of this in your bones. You have been lied to directly (“Your wife was home! I saw her in the hallway!”), patronized (“I just think it’s WONDERFUL that you’re out here! I love seeing idealistic young people getting out there and DOING SOMETHING! Ooooh, no, sorry . . . I just don’t give at the door”), condescended to (“I am not sure that you realize, young man, how the Clinton campaign has utilized the polyglot dynamics of the contemporary socio-political hegemonic realm . . . ”) and demonized (“Off my lawn, fa**ot!”). People will let you into their home, let you warm up in the parlor for a few minutes, lecture you on how the young people today don’t care enough about politics anymore, pontificate on how their generation was the last one to really get in the streets, and then pat you on the back and send you back into the night without a dime.

You have literally had hundreds of doors slammed in your face. You have been told — exasperatingly — to simply get a better job. Incidentally, the last parenthetical was an actual quote, recounted by a comrade who came back to the office pale as a ghost because of its being uttered by a man in a rage who gestured with a knife. Local cops make up stories and kick you out of their neighborhood for spite — this is particularly true, you find, in the more upscale neighborhoods. You are yelled at; you are scolded. Some people snottily demand identification, as if the neon jacket with the brightly-colored logo, nametag, and clipboard weren’t proof enough. You get the police called on you at least once a month. You informed in ways both subtle and roaringly obvious that you are not welcome here.

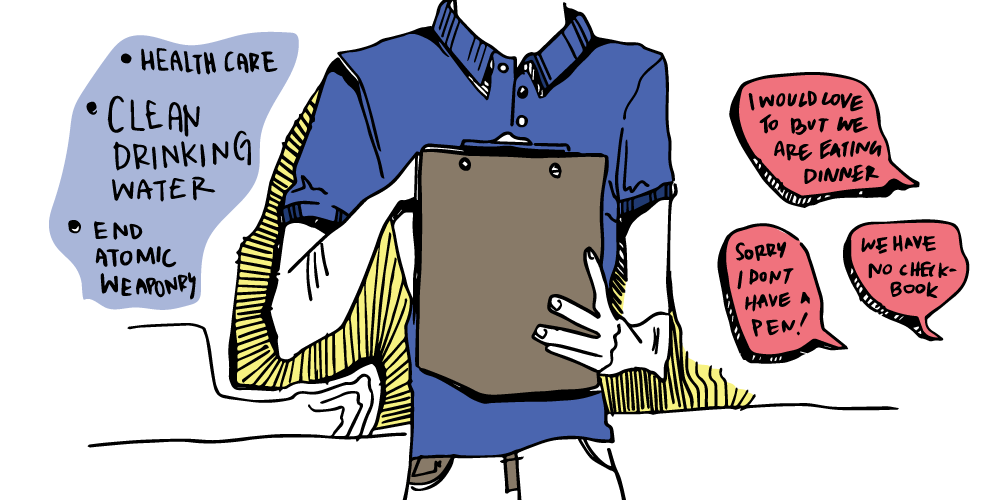

The main complaint is this: The people who tell you they’d love to give, want to give, are in fact just dying to give, but who won’t give to you. This is the ache, the rock in the show, the perpetual pain in the ass. If you’re given to introspection or insecurity, it can drive you mad. You have heard every excuse in the book and come to disbelieve all of them: we have no money, we have no checkbook, we have no pen, we aren’t citizens (legal permanent residents are fine), we don’t get involved in “this stuff,” we don’t do door to door, we’d rather do it online, we do it by phone, we only do it in the mail, we would not could not with a box, we would not could not with an ox. Sometimes during these moments, you swear on all that is holy that when the inevitable canvasser comes to your door in the future you will not only invite them in but feed them, massage their shoulders, and immediately write them the biggest check possible.

Your scorn is provoked by one very special assertion: “We’re eating dinner.” This is the unkindest cut of all. God forbid you to interrupt dinnertime! You hate it because it is so transparently hollow. You want to say: I know perfectly well what time it is. I know you’ve worked hard all day. I respect that. I get it. But believe it or not, I’m working too. But it’s not Shabbos and it ain’t Christmas. It’s Tuesday. This is the time when everyone’s home. You’re most likely munching take out and distractedly watching SportsCenter. You will eat again, I promise. We are not as much of an intrusion (honestly, we’re not) as you would like to make yourself believe. (Everyone loves to be annoyed these days, especially at other people. It’s a sign of sophistication). And I am not a solicitor, by the way. I have no vacuum cleaner in tow, no suitcase of Avon products for sale. This transaction will take three to five minutes, tops. It’s not that complicated. You’ll be glad you did it. You said, after all, that you liked what we do.

This is the crux of the matter, this is why dinner hurts. It is redolent of apathy and suggests the blasé self-importance of the armchair radical. It’s suggestive of the kind of flippantly cynical, solipsistic, desultory approach to the outside world that is so readily applied to the younger generation (not without reason, of course) by the older generations when there is more than enough shallowness and cynicism and cheap sarcasm to go around. People love to have opinions about politics- they just don’t like to think about politics all that much. Sometimes you find yourself in a position where you are called on to justify arguments you yourself don’t like very much, because of the nature of the situation in which you find yourself and what happens to have dominated the news cycle for the day. Tragically, idealism gets sidelined to pragmatics. This is politics, after all, not charity work.

You find yourself thinking: “Yes, I know the party/candidate/cause hasn’t been as vigilant as they should have been in doing X or not doing Y but you know what? Politics is the art of compromise (don’t I know it!). But this only makes our work that much more important. Give up now, go back to dinner, and the whole game is lost. The bullshit has got to stop. Write the check. Sign the petition. Get on the email list. Ultimately, it’s all about numbers. And the good guys are always outnumbered. We need to win the next election, get the bill to pass, pure and simple. We need clean drinking water, we need health care, we need to end atomic weaponry. We need to do these things. If we don’t get ourselves out of the dining room, or at least aid the ones who do, then the possibility of real change shrinks ever smaller and there’s less and less of a chance for something even remotely close to the America we dream of to actually happen.”

Nobody gives it to you. You gotta earn it. Turn away in disgust, disappointment, or apathy, and your opponent votes twice. And besides, isn’t there someone always complaining about how the corporate behemoth fat cats who rule this planet are buying up elections and politicians by the handful? Guess who dictates policy then? And doesn’t that make you mad? Don’t you think it ought to stop? Why won’t someone do something about it? If only there were a better way! Here, take a look at my clipboard.

It’s not that not everyone donates (no one ever expects that) but that there are people who don’t donate because they feel that it’s somehow fruitless or beneath them. Admittedly, it’s an unglamorous, ungainly, inelegant way to fuel the democratic process. Wearing a tux and sitting next to the celebrity of your choice at a swanky restaurant is so much chicer. Canvassers get treated like they do in part because they are living reminders of the nagging possibility of actual change. How else, pray tell, do people like Barack Obama or Ron Paul gain attention? It’s the grassroots, stupid. We are, each of us, the scrappy little reminders of the Silent Majority that there is more to life than quietly eating one’s dinner and grousing about The Way Things Oughta Be.

Sometimes, though, it’s a wonderful experience. You get dinner. The gig is not without its perks. It can indeed be, in the shopworn phrase, very rewarding. You have been fed sumptuous free meals by interesting people who want nothing more than to sit down and get to talking about what’s going on in the world today. They give you water. They give you gloves. They give you books. They let you in to warm up and have a rest. They listen, they joke, they swap gossip and stories and insights. You have sat for an hour with a jovial family on summer vacation in the Vineyard and been poured (at the host’s insistence) 18-year-old scotch in tiny glasses. You’re not supposed to imbibe on the job, but it would be rude to turn down an offered tipple or two. You’ve had money and sparkling repartee tossed your way amid a porch full of Christmas lights and a room full of people genuinely enjoying the presence of a new friend.

On a warm summer night, you sat with your witty and informed host looking out over the city lights and ruminating on the nature of American democracy. You’ve been given bars of Swiss chocolate by a wonderful old lesbian couple whose children recruited you to play dragon wizard in the parlor. You’ve met fascinating people, from all corners of the globe, with experiences that catch you aback. You meet people who proudly gave you money they themselves signified as being “hard-earned” without a trace of attitude or self-importance. You look at their hands and you know they mean it. You’ve seen people wordlessly give you all the money in their pockets without a second thought. Once, a gaggle of junior high school girls went peeking through the doorway on the afternoon of the junior prom and handed you lilies, giggling and running away. You’ve sat and spilled your guts (usually after a breakup) to obliging strangers who, after having taken in your tale of woe, decided to write you out a check after all — and get their spouses in on it, too. Cheer up, kid. You can do better. What goes around, comes around.

You’ve got stories worth telling. At the end of the night, everybody sits gladly down and counts up the day’s tallies, swapping stories about how nutty their night was. There’s nothing quite like the camaraderie that canvassers have with each other. Sometimes being at the doors gives you moments that you cannot describe. There’s no feeling like asking for a large amount of money from a stranger and actually getting it.

Nailing the speech you’re given, called “the rap,” which you painstakingly memorize and then improvise on at will. You can feel yourself saying the words but it’s like this rhythm is going through you, the way a great speaker will connect using sound, expression, and gesture and as you deliver it for the umpteenth time you somehow achieve this strange balance of passion with confidence and total calm. You watch people nod, automatically open their wallets, walk off to get their checkbook, smile a bit, and sign the paperwork almost in a daze. After all, you asked them to do it. Some people have this sort of power just pouring out of them, some people never really have it. But in time you learn to cultivate it, like any skill, and you too can make a living asking strangers for money. And if you can do this, what else could you do?

The clunking sound of footsteps breaks your reverie. You snap awake. You lean back, square your shoulders, shake your pen, ready your clipboard. You nervously run your hand through your hair. Oddly enough, the feeling is a little like asking someone for a date. You get butterflies. You’re about to do the hardest part of your job. You are not (usually) a volunteer. You are by design part gypsy, part salesman, and part politician. You are an idealistic individual who has gotten off the proverbial couch and actually “done something” about “it.” You are a loquacious gnat, buzzing in the ears of the hoi polloi. You are a part of something bigger than yourself. You are tired, humble, broke, energetic, and improvisational. You are, if nothing else, and despite everything else, an activist. •