Grant Hart is a songwriter and musician best known as a former member of the 80s hardcore punk band Hüsker Dü. Hart’s most recent album The Argument is an extended musical reworking of John Milton’s poem Paradise Lost.

This interview was conducted by students in the Honors course “Writing About Rock Music” at Drexel University with guidance from Smart Set editor Richard Abowitz. The conversation was constantly interrupted with laughter spurred by Hart’s infectious humor and sharp wit.

TSS: So I read that when you were growing up, you liked more of the 50s and 60s music . . .

GH: Well I considered what my peers were listening to and I thought, “God if these people are listening to this stuff, this stuff has to be stupid.” I was making an association that was false and there was a lot of stuff I had to go back and learn to appreciate, things that I skipped over before. Early 50s, the people that came from, let’s say poverty, and were exploited as songwriters but could make a hit record without any instrumentation short of their vocal sounds — that was really intriguing to me.

God, there are so many great ones but I would say I listened to a lot to Dion: Dion and the Belmonts, Dion as a solo artist. He had a beautiful voice. In retrospect it turns out that a lot of the groups of people that I liked ended up being a little bit more pop, a little bit more corny, a little bit more like Top Ten.

But the 50s is where the youth market really came into its own. In order to make things appealing to young people so that they would take their money and buy it, it had to be a little bit “pushing the envelope” from what was comfortable for their parents. The most important thing about rock ’n‘ roll is its use as a symbol of rebellion. Rock ’n‘ roll is all about rebellion.

I mean, life’s the reason the Vandellas are dancing in the streets. We’re not riding in the streets. We’re dancing in the streets. When you have people like some of these conservative douchebags that pretend to be rocking out and actually they’re buying up rock venues then the next thing you know the less-than-authentic music starts coming out.

There has been a paradigm shift between the 80s and now, as far as the honesty and the actual pushing of the envelope that is taking place with rock music. It’s gotten to be very producer-driven. It’s gotten to be like an assembly-line, Pro Tools environment where the only reason you need an artist is to have somebody that looks sexy so you can put their record on the cover so that there’s a direct association between what people are looking at and lusting for and what they’re actually hearing when they have their eyes closed, imagining that person.

TSS: You were speaking about paradigm shift with the sort of music recording between the 80s and now. What specific differences between recording and playing shows can you note between 1981 when you and Hüsker Dü released Land Speed Record and 2013 when you released The Argument? Is it easier or harder now to come out with music and promote it? What would you say about the differences there?

GH: Let’s say that older period of time…I have to admit to a certain amount of inhibition coming into work style, and it’s totally something that I have to recognize more when I’m actually making the music, especially the mid-80s with the altogether unrealistic accolades that Hüsker Dü was getting from critics. That made me think that, “God everything is lasting so long in the public’s consciousness that I wish I would have done a second take on that vocal. I wish we would have spent twice as much on that album. I wish. I wish. I wish”. And so I started moving so damn carefully, instead of just doing it, as the Nike people say. I think maybe that’s the encroaching conservatism that comes as your age progresses but if it is — that’s the only way that I can detect that happening with me. You start playing for the big timeline once you realize there is permanence in what you create, or permanence in its appreciation.

TSS: When I was reading up on Hüsker Dü, I came across many positive reviews about Zen Arcade but for you personally — if you had to pick one album, which of Hüsker Dü’s albums would you say defines the authentic sound of Hüsker Dü?

GH: Land Speed Record just because it’s the least contrived. Now, if you’ve studied up on the history, you know that there is a big chasm that grew and grew and grew between me and what’s his name? [Bob Mould]

A very wise friend of mine, Curt [Kirkland] from the Meat Puppets, said in relationship to Bob [Mould], that he was the one person that is the most motivated by fear of anybody he has ever come across. If you’re a person who is motivated by fear, and you are always watching your step and being very contrived, then a person who is not so motivated is going to come off as being a very dangerous and reckless to be around. And as the grip upon the members of the band tightened…Once you become successful, you’re trapped because you want to do exactly what you’re doing with just enough articulation to keep it interesting for yourself but you have to find your niche, and you’re going to carve it into a rut.

TSS: One of the things I noticed when I was listening to your album The Argument was just how eclectic it is. It really spans a wide range of genres and there’s a lot of different sounds… My question is: how difficult was that for you to incorporate all of those different sounds in the album? What was the creative process like? Could you give us some insight in to what goes on?

GH: It was actually very liberating because I knew at the onset that a single album was not going to do it, that a double album was not going to do it, but the constraints of the market dictated that I not make it a triple album. It’s an unsalable thing.

There are some great triple sets but come on. Sandinista! [The Clash]? There is a lot of wastage on that. I guess I’m not a big enough Clash fan to appreciate it.

What I did is having somewhat enough familiarity with the poem [Paradise Lost] that I knew the entire…basically the trajectory of the story. What I did is, I went through it a couple more times and I read lines of things from it that I felt totally unnecessary for my version of it. Mine was actually inspired by access I had to a Burroughs treatment of Paradise Lost which was only one-and-a-half pages long since it only dealt with the episodes right after the fall. I thought, “Geez, no one really writes about the entire thing.” And soon I discovered there is a reason why. It is a bulky boat anchor written at a time where the written word was for the wealthy, the literate…I don’t know what percentage of people were literate but I imagine it was less than ten percent.

Everything that they read, all of their TV, their Internet time — every spare moment that they weren’t whipping their serfs, was involved in reading for entertainment. Oh, and some live music, of course.

So what I did is I ditched the religious content immediately, and tried telling it as a story surprisingly about human nature. The gods and demigods in Paradise Lost are crazy human. I mean, they are human. You don’t get too much of God in the thing, except that he’s the human behind doors that’s running the show.

As far as the eclecticism of the music, it was given an expanded, larger canvas. I could go off on these…I could check out new musical campgrounds and dwell there for a while, and experience the joy of that kind of expression. I never was very comfortable in the same way — let’s talk about that band again — the same way that Bob Mould was with the screaming, hardcore thing.

From the very beginning, I was doing something else, and that’s just an observation. It’s not an either/or; it’s not a boast or a criticism. It’s just that I couldn’t express anything but extreme pain with screaming, and I pretty much stick to doing that when I am injured.

TSS: So I’m curious in a more broad sense. What makes a song worthy of being the title track of an album?

GH: I wouldn’t know because I’ve never done that… What makes a song worthy of that? I would think it’s a business rather than artistic decision. It’s a means by which you concentrate the attention, given an entire group of songs onto one song. Now maybe in the way that I work with song cycles and things like that, there would be a possibility for a title song — one that is the summation of everything I’m trying to get across… but I’ve never been there.

TSS: Well, you titled New Day Rising, “New Day Rising.”

GH: That wasn’t me. I guess, Last Days of Pompeii, I did.

TSS: Well, there is a song called “The Argument” on The Argument.

GH: I guess I decided on that title beforehand…Okay, I lie. Hey, I’m learning too!

“The Argument” itself is basically an inverted poem which rhymes at the ends of the lines. But there is the “word overlap” in the middle that links together the two different voices on it, which was excellently captured when I performed the song with a 12-piece orchestra in Berlin. That kind of worked for me to title it. I guess I named that song after the album, not the album after that song, when I really think about it.

TSS: Well, I’ll tell you why I thought it was called The Argument, because when Milton does those little summaries before each book — they’re called “The Argument”.

GH: Oh really?

TSS: So I thought you meant that The Argument being the summary of the chapters.

GH: That’s where I got the title. After seeing so much foolishness that comes up when you Google Paradise Lost, you get everything from motorcycle companies to pornographic movies named that. It’s become meaningless by its overuse, and most of it tended to be a lot of dark imagery — stuff showing up in satanic looking letters — and not incorporating any of the hope and the love and the redemption that is also there. The majority of the Milton poem is about very positive things. The darkness is like a jawbreaker; it doesn’t dissolve immediately. But there is a lot of sweetness in life there.

TSS: You touched on this with the other questions before, but my question was really about your particular creative process. When you’re writing a song, do the words come to you first or the music? Or is it a simultaneous thing that all comes together?

GH: The words, and…this is where I may have dug myself a little bit of a rut. At one point in time — I guess it was while making Last Days of Pompeii — I realized that in the order of things I could improve a song much more by not codifying the lyrics first thing.

I do the recording of the vocal as the final step before mixing the song — usually nowadays, right before mixing it, as part of the mixing process. You get to do this karaoke thing where you’re sitting there. You’re singing something to tracks that are going to be on the record. You’re not listening to a click track or a single guitar, or something like that. You get to bounce yourself off of all the accumulated instruments, the dynamics and everything.

But having embraced that technique, I’m almost kind of, “Oh the verses, oh yeah, those come last!” because I can always make the song better if I don’t staple down the context of something immediately. I’m freer to be more creative, which is true, but it has allowed me to not-exactly-be “Johnny on the spot” when the time comes to finishing the lyrics of a song. As a matter of fact, I’m on my way to a studio session that I’m going to be playing bass rather than doing vocals because I’m unprepared — another pitfall of self-employment, but I got a good boss.

TSS: I noticed, in the album The Argument, you use a lot of different musical instruments. I thought I heard the organ, wind chimes, and crickets in the background —

GH: No crickets. That is an actual recording of Sputnik.

Sputnik — once the Russians let everyone know what frequency they could listen to it on — because they had to prove it to the world that they had done it. As Sputnik goes continually towards the next horizon, because of the Doppler effect, it would become more flat — every beat. And also, people would broadcast on the same frequency on their own radio sets and say things like, “We are going to invade you! We are the men from Mars, and we’re coming to attack Earth!” and just being playful and hoaxing and things that people did because they had the equipment to do it. They were the hackers of 1957. And so therefore, it was very hard to find an unaffected recording of Sputnik that didn’t have some gibberish or didn’t go severely flat.

We followed this tape, and lo and behold, it was the exact, right pitch, to 100ths of a tone, and it was rhythmically so perfect that it would take 45 beeps for it to be noticeably out of time. Now that’s a better ratio than most professional drummers. Most professional drummers are going to be out of time by the second verse. But the trouble then was because of the Doppler effect it would become flatter. So we had to employ digital of an entire analog recording, mastered analog, mixed from tape to tape. We had to make a loop of these beats that didn’t go flat. There you go, and now you know something interesting that you didn’t know a moment ago but that’s some of the song and dance that you have to do when you are so ingrained in one work style or one technique — in my case, analog recording. That’s where I learned all my tricks. Now, my opinions are going to be not anti-digital, because that’s like being anti-automobile and riding a horse around downtown.

Usually when people are working digitally, they have the opportunity to just keep adding tracks. There are an infinite number of tracks you can record to make a song. The problem is when you have that freedom you don’t have any limitations that are going to give you the need to organize your recording into a plan. How are you going to make a million tracks into two tracks — left ear and right ear? So, organizationally speaking, 24 tracks are just about perfect. I’ve rarely had the need to record more than 24 tracks. If I ever have to, I sub-mix. I will take four tracks and make it into one track before it is master-mixed.

TSS: I’m not familiar with your previous work so I was wondering — with The Argument — were you trying to be a little bit more creative, or be more of yourself, and use these sounds differently because it is pretty different from your standard artist that sticks to guitar, bass…. Is that you breaking out of your shell or putting your personality on the album?

GH: I think it had a lot to do with losing 90% of my possessions [in a fire], and sleeping on mutual friend’s couch for 5 months. Either I had to dog paddle like crazy to get back to the year 2000 or I could take an artistic leap of faith, and re-invent the whole shebang. And I took the artistic leap of faith, and it was a great experience, and I hope none of you are challenged the same way but challenge yourself!

TSS: How did you go about combining themes of good versus evil and duality in The Argument?

GH: Well, you look at humanity. Part of the process is I’ve been able to see some good in people that wouldn’t be allowed off the railway sign in a different world. I tried to find not so much the bad in good people or the good in bad people. And I use the word good and bad with quotes around them, of course. I tried to find why people carry with them such conflict in the first place. I tried to look for a key to their character and to see if I’m the same way in any way, shape, manner, or form.

TSS: What was the first review you ever read of your own music, and how did you feel about it?

GH: There was an old chapbook — a little tiny magazine published by high school kids who were probably my same age that reviewed… not necessarily a Hüsker Dü record or Hüsker Dü performance but the fact that Hüsker Dü existed. How do I feel about it now? I guess it makes an interesting first page in the press book — in the metaphorical press book. This sounds like papa’s ass speaking and perhaps, that’s the case, but from little acorns, mighty oaks do grow.

TSS: I’m recalling a Hüsker Dü lyric, which I assume you wrote because it was sung by you: “Sunday section gave us a mention/Grandma’s freaking out over the attention.” As Hüsker Dü started to get written about, did your family take the band seriously or did it change how people saw you in your world? Did the media attention impact you?

GH: South St. Paul was like a part of the south, and I was Marcus Garvey!

TSS: I really want to know what your family thought of your music, honestly.

GH: My father was a vocational guidance counselor after having been a shop teacher. Up until the time that he appointed himself master of ceremonies at the party when we signed to Warner Bros., he was always, “Well, you — you enjoy music, and it’s cheap entertainment for you but you’ve got to find something serious to fall back on!” and blah blah blah.

And here’s a man — the trajectory of his life was from lily pad to lily pad. The guy never had to get his fuckin’ feet wet once. Here’s a man — when he finally decided to cut everybody loose and die like a man — his last words to me, on the day before he died, I was fluffing up his pillow, and he said to me, “Cut that out. There’s people here that have been trained how to do things like that!” But I digress.

When I was 10, my brother who had been giving me drum instructions, was killed in a road accident. There was this duality that up until the time I was 14 or 15, anything I did involving music was very, very sweet to my parents because they were seeing their lost son in my shadow or me in his shadow.

The farther you get away from the immediate family, the more bitter people get where it’s like, “Well, Ann and Vern’s kid — he makes millions of dollars playing music, and I don’t know why he doesn’t buy them a better house!” Blahlalala. Playing hardcore punk, yes. But if we could choose the way we were appreciated, we wouldn’t do anything worth being appreciated for.

There is a certain amount of gratification that comes from speaking in front of people like you that hopefully are going to pick up the torch and carry it on into the future.

TSS: Why Paradise Lost?

GH: After having released Hot Wax, which was a very schizophrenic album, I was invited by another band to come up and make my next record with them but I was soon to discover that they weren’t really into making my record. They wanted me to make their record — write the songs and put my name next to theirs — a whole different work style.

I had written a rockabilly song that dealt with the myth, the legend of Echo and Narcissus. Chuck Berry has sung about the Venus de Milo. So, here is a rockabilly song about this ancient, international Greek archetype. I was looking as a lot of artists do when they reach mid-period of their life to embrace more long-lived things. I was playing to eternity. I was etching in granite. I was carving my napkin rings out of Carrera marble.

When I was visiting a friend who had been William S. Burroughs’s secretary I saw treatments that Bill had been worked on that could be theatrically exploited like the thing that Tom Waits used for The Black Rider piece. I thought, “Wow, this is crisp for my bill,” and when I heard whom they were thinking about doing the compositions, I was incensed. Rufus Wainwright has nothing to do with William Burroughs! I mean, William Burroughs wouldn’t even occupy the same room as Rufus Wainwright! I guess I’m not impressed.

Before I even left the driveway, I was like, “I’m going to do this!” I think it’s a great story. It’s a bigger chunk of material, and I was looking to work in a big chunk. I had no idea that fate and life’s curving road would lead me to the perfect situation in which to do that.

TSS: What impression did you want the listener to have of Satan in The Argument?

GH: I was not going to play with religion. There is no time during the course of The Argument that I ever referred to that character as anything but “Lucifer.” What other people choose to call him is up to them but I chose the Promethean Lucifer, the bringer of light — the one that inspired the enlightenment, that threw religion under the bus so that things like algebra and science, and sewer systems could prevail.

The Lucifer character in Paradise Lost is classic anti-hero. Could you imagine Dirty Harry as Lucifer in Paradise Lost? Or maybe Escape from Alcatraz: “I gotta get out of this hell!”

TSS: As a producer, I’ve always thought that Phil Spector was a big influence on you. Am I mistaken?

GH: Well, he took recording technology and broadened the hell out of what people were doing with it. Now, he’s mad. He’s an abusive person but he had a vision, and I think that the problem with Phil Spector is he stopped embracing projects, thinking that they were unworthy of him. But anybody that can go from “Da Doo Ron Ron” to “River Deep – Mountain High”…There’s got to be some appreciation for that person, good, bad, and different. It’s interesting.

TSS: Any final thoughts?

Do yourselves honor, and have a great, great life. I hope to hear of you.

Take an afternoon, and visit the Arensberg collection at the Philadelphia Museum. And make sure you give the bicycle wheel by Duchamp a good spin, whether you get kicked out of the museum or not. It is meant to be rotated! •

This interview was prepared for publication by Kristen Laiz. Student interviewers Christina Alleva, Kendall Currier, Hannah Donnelly, Kyle Killian, Heather Krick, Kristen Laiz, Trevor Montez, Teresa Moore, Julianna Quazi, Grigorios Papadourakis, Alexander Rogers, and John Wismer contributed and asked questions.

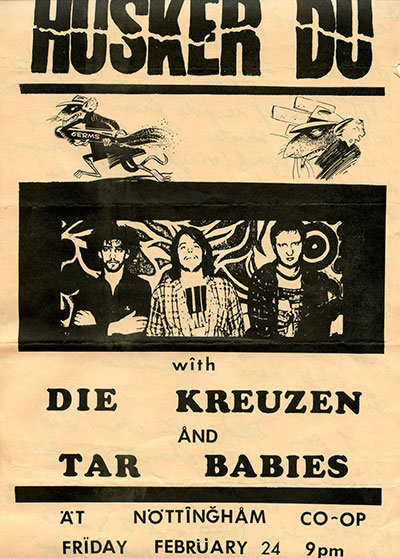

Photos by Iburiedpaul via Flickr (Creative Commons) and Drazen Smaranduj via Flickr (Creative Commons).