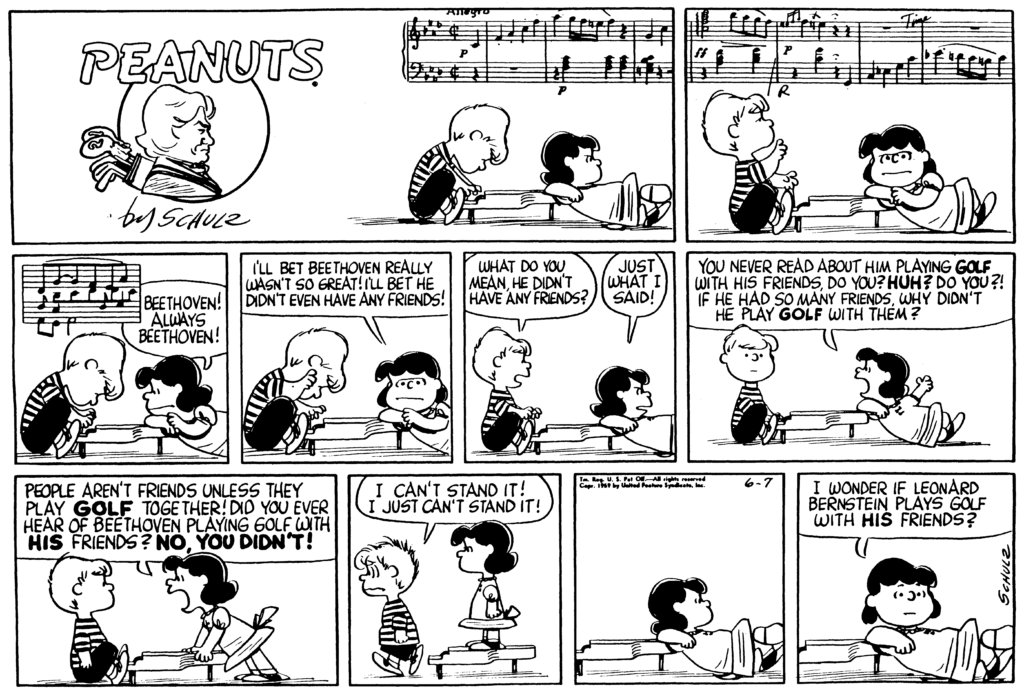

Lucy has never been able to make Schroeder love her. But she has a fail-safe method to arouse his passion: impugning his beloved Beethoven.

PEANUTS © 1959 Peanuts Worldwide LLC. Dist. By ANDREWS MCMEEL SYNDICATION. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

The Peanuts world is a child’s world, inhabited exclusively by children (and a dog). Schroeder’s piano is just a toy — one octave, with painted-on black keys. And yet the music that Schroeder produces is abundantly real: not all-purpose symbols signaling generic <<¯background music¯>>, but a specific piece (the opening of Beethoven’s Sonata in F minor, Op. 2 No. 1, first movement). The notation is not only accurate, but it is also personalized (does Schroeder have a piano teacher?!), with cues to observe the rest in the left hand and to mind the tempo for the restatement of the theme in a new key. Panel 2 depicts not a direct continuation of panel 1, but seven measures later in the piece. Time has passed; we’ve arrived at a moderate climax, rendered with a right-hand flourish and reverent upward gaze by the little pianist. This display makes Lucy grimace. But she goes on to listen for quite a long time: Schroeder is over fifty measures into the second movement of another Beethoven sonata (Op. 2 No. 2 in A major) when she snaps, “Beethoven! Always Beethoven!”

In the same way that Schroeder plays real Beethoven sonatas, Peanuts’ humble means — simple drawings, childish words — communicate volumes, bringing awareness, perspective, and the potential for nuance to Big Questions. When jealous Lucy finally loses patience, she draws attention not just to the uniformity of Schroeder’s repertoire, but also to the seemingly universal ubiquity of Beethoven the composer. Why Beethoven? Why so much Beethoven? When she goes on to declare “I’ll bet Beethoven really wasn’t so great!” and mocks the composer for not having friends — or worse, not having played golf with friends — her simple measure for greatness again points to something complicated. What constitutes “great”? What makes “great composers” great?

•

At the college where I teach, fall semester 2020 was supposed to have ended with a Beethoven extravaganza: a series of gala concerts, a festive and resounding “Beethoven, always Beethoven!” worthy of the 250th anniversary of a Great Composer’s birth. Our exceptional student orchestra, chorus, chamber groups, and soloists were to perform to a packed, appreciative hall; students in my musicology seminar would, with blossoming erudition and cutting-edge technical prowess, deliver pre-concert lectures, program notes, and an interactive exhibition in the lobby. But already by August, we knew that the bash for beloved Beethoven would be another coronavirus casualty. Already by then — it had been an end-of-innocence summer, a tumultuous and taxing summer — the original plan struck us as quaint. An idea for an era we’d outgrown.

How the fall semester actually ended: me sitting alone in my campus office, within earshot of the concert hall (silent) and the lobby (empty). Some of my students were in their dorm rooms nearby while others were in their parents’ homes far-flung across continents and time zones. We were together by virtue of a “cloud-based video conferencing platform for virtual meetings.” Each of the twelve student faces filled a panel in the grid of my computer screen. Two-dimensional images of three-dimensional spaces. Three rows of four panels. In color, like a Sunday comic strip.

Image by Freepik

Instead of reveling in Beethoven and the present moment of his 250th birthday, we were examining artifacts from the 200th, Beethoven’s Bicentennial in 1970. Commemorative postage stamps from Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Senegal, Monaco, the Soviet Union, Greece, Mexico, Albania, Cameroon. Beethoven-inspired satiric commentaries by avant-garde composers Mauricio Kagel and Karlheinz Stockhausen. The pop-chart topper “A Song of Joy” by Miguel Rios, adapting the “Ode to Joy” tune from the Ninth Symphony. The first audio collection of Beethoven’s complete works, a set of eighty-five LPs produced by Time-Life and Deutsche Grammophon. Beethoven Bicentennial issues of Musical Quarterly, Saturday Review, High Fidelity, and (this is where we lingered) a special section of the New York Times.

Maybe it sounds a bit pitiful — as if, since no one came to our birthday party, we were consoling ourselves by poring over scrapbook memories from celebrations past. As if we were reminiscing about the good ol’ days, when we (music students and musicians) were important because Beethoven was important. But in fact, we were not being sentimental. We weren’t feeling sorry for ourselves, or for Beethoven. No one was in the mood to party.

•

“Recordings — Beethoven Bicentennial,” dated the Sunday after Thanksgiving, November 1970, is not the familiar Sunday New York Times “Arts and Leisure” section, Section 2, but a special, one-off section at the very back of the newspaper: Section 14. On the front page, Schroeder and Lucy (and scowling Ludwig himself, with golf clubs slung over his shoulder) set the tone. Also there, and on the pages that follow, scattered within a thicket of advertisements (for LPs, record and cassette players, and an array of other audio accessories) pitched for the kick-off of the holiday shopping season, are commentaries on Beethoven from five then-prominent writers and musicians. Their perspectives are at odds: defensive, dismissive, worshipful, skeptical.

At the top of the front page, Catherine Drinker Bowen describes Beethoven’s music as “extraordinarily philosophical.” A grand notion that in her youth (she admits) she would have called “crazy” — that Beethoven’s music could contain “wisdom communicable and lasting” — is now, from the perspective of her “long life” and “thirty years of working at” the late string quartets, something she can affirm: “I know now that it is true.” From Beethoven, “one receives a message, at the same time profound and strangely impersonal.” And so, she concludes, “we stand in awe and gratitude.”

But on page four, Charles A. Reich assails classical music in general as “dainty or mushy.” In his view, “not even the turbulent fury of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony can complete for sheer energy with the Rolling Stones” whose “[d]riving, screaming, crying, bitter-happy-sad heights and depths and motion,” are dimensions “unknown in earlier western music.”

In our discussion, the students and I construct an image of Bowen, in the twilight of her storied career as a biographer of Great Men. She is contemplating a glass-encased Beethoven, from a respectful distance and in reverent stillness. In contrast, we envision Reich, whose 1970 countercultural manifesto The Greening of America was hot off the press and making waves, crashing into and shattering that glass case as he becomes physically possessed by what he calls “the new music,” which, he says, “rocks the whole body and penetrates the soul.”

Speculation ensues. The students imagine editors (wearing heavy sideburns and wide, earth-toned ties) around a newsroom desk, indecisive and discomfited: how, in 1970, should the New York Times cover Beethoven’s Bicentennial? After a tumultuous decade, 1970 had been a no less tumultuous year. On this particular day in November, the front-page headline was “NORTH VIETNAM HIT AGAIN”; the Week in Review section headlined “Cyclone May Be the Worst Catastrophe of the Century.” (The Bohla Cyclone took over half a million lives in present-day Bangladesh, making it the fifth-most deadly natural disaster ever.) The year had opened with the disorderly and conflict-ridden trial of the Chicago Seven, then moved on to the heart-stopping “Houston, we’ve had a problem” on Apollo 13. It saw the secret invasion of Cambodia and the tragedy at Kent State. The voting age lowered to 18. Simon and Garfunkel recorded their last album; the Beatles broke up; Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin died.

Was the answer settled upon at the Times to invite commentators with opposing views? To juxtapose (Schroeder’s) veneration (Bowen) with (Lucy’s) take-down (Reich)? To stage a grown-up version of the debate around a toy piano?

“I bet Beethoven really wasn’t so great,” Lucy sneers; Schroeder asks her to elaborate (“What do you mean . . . ?”), but to her, the point is self-evident (“Just what I said!”). As class discussion continues, it’s as if the students are channeling what Lucy might, were she not so impatient, go on to say: Who are you, Catherine Drinker Bowen, to determine what “wisdom” is “lasting”? You haven’t seen what we’ve seen. And what even is this wisdom, this “message,” that one receives from Beethoven? Why would we want it, especially if it is “strangely impersonal?” It seems that Bowen’s devotion (“awe and gratitude”) and her abstraction chafes, aggravates. We’re in the middle of a pandemic, a national reckoning on race, a still-contested presidential election. No one wants to be a Schroeder.

But it is also Lucy — rendered in, and inclined to speak, in black and white — who introduces shades of gray. Eventually, we rejoin her in the thoughtful silence of the penultimate panel. Across the twelve panels of my monitor are twelve faces pondering.

•

Howard Klein, a then-regular classical music critic at the Times, begins his contribution by reminiscing about winning a talent contest as a youth by playing the “Moonlight” sonata. The moral of his story: “Beethoven always wins.” This is a familiar trope, common to many of the primary source readings on the syllabus this semester. Beethoven, synonymous with triumph: the hero who struggles with, yet overcomes deafness, who defies the culture of aristocratic privilege and prevails based on his sheer merit, who goes on to revolutionize music and essentially conquer the world. It is a narrative captured in the Fifth Symphony’s arc of adversity, represented by C minor, overcome by celebratory C major. Klein repeats that “winning” note in his conclusion to profess Beethoven’s greatness in terms of enduring relevance: “Our age can listen to his victory song. Perhaps he sang it for us.”

Klein’s article prefaces his list of recommended Beethoven recordings, apparently the centerpiece of the special Section 14. (The best pianist wins by playing the best composer, then returns the favor by promoting the best recordings of the best pieces.) In 1970, as now, “Beethoven” was not only a historical figure — a someone — but also a something to be bought and owned. And in 1970, even more so than now when we can listen promiscuously on YouTube or Spotify, making the choice of which Beethoven-object to own was an investment and a commitment. For that, readers wanted advice. In presenting his advice, Klein states that (the term “personal” in the title notwithstanding) the first principle informing his selection is an objective one: “faithfulness to the printed page” in notes, dynamic, accents, tempos, and repeat signs. “I liked those performances which adhered closest to the letter and spirit of what Beethoven wrote,” he declares.

Winning: now that sounds to us like a definition of “great” that Lucy, just like Klein as a youth, could get behind. Likewise, she’d probably be enchanted by a list of “best” recordings, and the ostensibly objective criteria that produced it. But Klein’s “faithfulness” to Beethoven, his “adherence” to the sacred text of the score, hews towards our idea of Schroeder. From the upper right-hand corner of the “best recordings” list, Beethoven himself gazes down approvingly. Notably, this is not the universally familiar portrait, but a less familiar one (by Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller) from the end of the composer’s life. It signals retrospection à la Bowen: the wisdom of age, seniority, and experience.

The counterpoint to Klein lies adjacent on the page, immediately to the right while Beethoven gazes unawares to the left. It is a commentary on Beethoven contributed by Tim Buckley, “rock star.” Wizened elders and purists of Klein’s ilk must have groaned to see a “rock star” byline. But anyone familiar with Tim Buckley’s work must have groaned, too, for a different reason: while Buckley (age 33) continued to play some of his relatively accessible rock songs like “Goodbye and Hello” (1967), by this point in 1970 he was creating completely original sounds from the raw materials of rock, folk, jazz, and classical avant-garde composers like Berio, Penderecki, and Messiaen. His album Lorca (released that year in June), for example, started with a 10-minute title track in 5/4 meter. Highly dissonant, it centered on a C-minor (!) drone, with text obscured by a shuddering vibrato, low moans, and high-pitched wails. For making these inaccessible, uncategorizable songs, Buckley was paying a steep price with his public. Rock star? Neither word was accurate.

Like his music, Buckley’s essay is artfully abstruse and audaciously abstract. It requires repeated readings, just like his music demands repeated listenings. (If Lucy read it, she’d be rendered with spiralized eyes and a crumpled mouth.) But Beethoven’s “relevance” is plainly on Buckley’s mind too; he uses the word three times in eight short paragraphs, including right at the beginning, as if to pick up where Klein leaves off. “Beethoven’s relevance to music for all time has its own reasons,” he opens. And then he equivocates. In the second paragraph, he wonders just how often music ever is “really relevant” to people or if it “just supports a fashionable movement,” as in, “today’s protest song is tomorrow’s bumper sticker and so on.” “No communication, just part-playing — read the charts and fit in.” (Does he mean sheet music? Or, more brazenly, pop charts? Klein’s chart, with its preferential formatting and placement on the page, lies mere inches away.) “Part-playing” (another word that Buckley repeats three times), he says, results in culture that is “bought and sold and planned out to get a response, and then the response is planned in order not to get in the way of the next one.” Eventually, we develop a sense that Buckley’s Beethoven has nothing to do with all of this. Buckley’s Beethoven is “too personal to isolate, too intimate to forget, and too spiritual to sell.” Buckley is awed but not awe-struck. If people don’t understand Beethoven, it’s because they don’t have a personal — “alone, only yourself and what you’re good for alone, no banners” — or unfiltered experience of his music. Take away the part-playing and then, only then, you can let others in when they are no longer influences. Buckley wants the listener to perceive Beethoven apart from cultural capital or any other quantifiable “use” on offer. To hear Beethoven apart from the satisfaction of possessing (the right recordings of) him. Apart from the desire to partake in his victory song. Perhaps even apart from the desire to receive wisdom or move the body and its emotions.

Finally, we, the grid of twelve, return to the front page, where Lucy, alone in the silence left by Schroeder’s exasperated departure, muses, “I wonder if Leonard Bernstein plays golf with his friends?” Does she assume that Bernstein is great and therefore second guess her doubts about Beethoven? Or does she stick to her reasoning (golf = friends = popularity = greatness) and now question the greatness of Bernstein? Either way, it makes for a sly introduction to the other essay printed directly below the strip, by . . . Leonard Bernstein.

Beethoven’s bicentennial year was a busy time for the celebrity conductor, arguably at the peak of his career. His packed schedule included back-to-back performances of the Ninth Symphony with the Vienna Philharmonic and the Boston Symphony, with just four days between the last Vienna performance and the first Boston rehearsal. That experience, Bernstein describes in his essay, gave him a new perspective on, caused him to discover a new element in, Beethoven’s music. “Of all qualities, this would be the least expected,” he admits, “and yet, there it was to be found, buried” under layers of clichés: the “pure simplicity of childlike belief.” In particular, Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” finale requires, according to Bernstein, “prepubescent faith […] that only children (and geniuses) really possess — to go all the way with him as he cries out ‘Brüder!’…” A “child-inspired cry,” when all men become brothers.

“To play Beethoven’s music is to give oneself over completely to the child spirit.” After some thoughtful silence, one of the students rereads this sentence aloud, then tests an idea. To believe in Beethoven like Schroeder believes in Beethoven?

Her tone is not cynical, but neither is it naïve. It is at once a little bit reluctant and a little bit intrigued.

Someone else offers that Bernstein is less like Schroeder and more like Lucy, for he concludes his essay with questions. “How childlike was I capable of letting myself become?” Bernstein asks himself about the two performances. “How trusting? How willing to suspend disbelief?” Then, his questions gain momentum. “How desperate about Vietnam, Israel, the Soviet Union, or a newly lost friend? How hopeful for new music, for the black American, for peace? Brüder!” It is a gradual crescendo of questions that leads to a realization, then culminates with a sforzando: “Brothers!”

Bernstein’s “childlike” isn’t a state of being separate from the realm of adult, real-world, problems. Speaking over one another, the students restate the questions in present-day terms. “How desperate about” white supremacy? North Korea? Refrigerated trailers backed up at the morgue? A “newly lost friend” — the one who stopped communicating after we were sent home in March for the rest of spring semester, and who never returned in the fall? A newly estranged favorite aunt, entangled in conspiracy theories? A newly lost grandparent, who died alone in her nursing home, without family allowed to say an in-person goodbye?

“How hopeful for”….?

Even if the students didn’t ask or answer Bernstein’s second question aloud (and they didn’t), it felt like there was room now to imagine doing so. Belief, faith, and trust. Reality paired with imagination; desperation paired with hope; greatness that encompasses both. Perhaps this is what Schroeder believed in all along.•