From social commentary to commodity, Janette Beckman’s career is in many ways a classic model of the popular memory of punk rock. As a young photographer who documented London’s youth cultures in the 1970’s and early 1980’s, she found success and opportunity earning commissions from magazines and record labels. Like Johnny Rotten and Joe Strummer, Beckman sold her creative labor, just as thousands of artists and musicians have done for generations. Whether or not punk “sold out” is an oddly recurring but nonetheless pointless question: it was embedded from the beginning in contemporary commercial culture — in the ideas, languages, icons, objects, exchanges, and processes of consumption. It was always about selling, in one way or another.

Nobody would seriously ask whether Beckman has “sold out.” But such a ridiculous question came to my mind at an exhibition of her work at the Punctum Gallery at Chelsea College of Arts which features a mash-up of her photography of the punk and hip-hop scenes in New York and London. For a start, the free exhibition is part of Punk London, a program of events in 2016 funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and the mayor of London which will include events at notable punk-rock venues such as the British Library and the Museum of London. Picture Sherlock Holmes with a mohican, perhaps.

That punk is to be memorialized at such bastions of British establishment power is a little bizarre, especially when, in getting lost in the tatty corridors around the Punctum Gallery, there seems a universe of difference between university galleries like this and the corporate-sponsored cultural behemoths on Euston Road. Punk has always been full of contradictions, as John Cooper Clarke told the Financial Times: “It was a broad church. You’d get your individualist rightwing libertarian types, then there’d be the change-the-world-type socialists.”

How much selling is bad selling? Both scenes have, since their respective births, been concerned aesthetically and intellectually with success: hip-hop often with a critique of money and wealth; punk with dirt, decline, and the inanity of consumer practices. The contradictions in both punk and hip-hop are that they were for many people set up in diametric opposition to commercialism. Accusations of having “sold out” often come from punks and observers who undoubtedly saw the movement as a rebellion against establishment, perhaps having even pogo’d or spat or postured with that in mind.

Such a feeling of betrayal or of having been hijacked is quite legitimate. In its confrontations with the music industry, the Queen, the government, or acceptable manners, punk was at least on some level undeniably anti-establishment. However, many aspects of punk — its material culture, its music distribution, its use of celebrity and its (ironic sense of) consumptive behaviors — were not just of little threat to hierarchies of British and American power: they crisply tessellated with prevailing economic modes of production, exchange, and consumption. Punk, for all the influence it had on cultural postmodernism’s defenestration of structural narratives, was very stubbornly a giddy groupie of a particular kind of Marxist modernism — of the well-trodden plots of proletarian and bourgeois antagonism.

In the spirit of punk, this exhibition is a bit of a re-appropriation, having been curated in a similar form as Catch The Beat at the Morrison Hotel Gallery in 2011, a ten-minute walk from where the iconic CBGB once stood in Bowery, New York. (CBGB is now a clothes shop.) The gallery throws together Beckman’s images of Strummer, Siouxsie Sioux, and Debbie Harry alongside her shots of hip-hop pioneers like Salt-n-Pepa, Slick Rick, Run DMC, and Afrika Bambaataa. Well, not quite alongside. Here the images are presented separately, prints from the two scenes facing each other on parallel walls. What might have been presented as a transnational dialogue — there are artists from both genres pictured in both New York and London — is more of a comparison: two scenes, distinct cultures, join the dots yourself.

Joining those dots, though, is a rewarding experience. The exhibition, with its allusions and juxtapositions, is a provocateur of questions and insights. Here the similarities between punk and hip-hop leap off the stage: youth, rebellion, commercialism, working-class culture, and opportunity. Those themes may be concomitant with many post-war Western youth subcultures, but the differences are apparent, too. In one of the most striking mash-ups, a Beckman photograph of a punk fan playing air guitar in a pit of soaking mud at Loch Lomond in 1981 has been transformed: a river of blood runs horizontally across the image and the fan is no longer thrashing a solo but dying, clasping flowers, in a pose like John Everett Millais’s Ophelia (1851-1852). (I am grateful to Natalie Anastasiou, the curator, for pointing this out.) The mash-up, by Christos Tolera, has de-punked the original image, deftly demonstrating precisely what is unique about punk in the first place. For example, it seldom incorporates mud, rurality, or Shakespearean allusion (except in the name “punk,” which Shakespeare used to mean “prostitute” in Measure for Measure). As with much of this display, the incongruity is illuminating.

Beckman’s image of Salt-n-Pepa, one of the first all-female rap groups, is another example of this delicious proximity. In the 1987 shot of the group, their outfits are colorful and modified, distinctly American in their baseball garb, but with militaristic boots, striking gold chains, kente cloth hats and macho poses that speak both to the colors and customization of New York punk rock, as well as the branding, iconography, and productive reproducibility of hip-hop street style.

Much of the power — and difficulty — of this display, though, comes not from similarity but from difference. A photograph of Siouxsie Sioux performing at the Roundhouse in 1977, one of Beckman’s most iconic images, captures the quintessential punk-rock style. Siouxsie Sioux wears oversized, overall-style trousers with a tie and a black shirt. The appropriation of working-class uniform is a common feature of the punk aesthetic, an ironic answer to a Foucauldian problem: the normalizing practices of discipline and order represented by the work apparel versus the consumptive and performative agency of the liberated individual. Punk style — in both the UK and the US — had little regard for buying clothes that were ready to wear off the rack. Creation and appropriation were central. Unlike hip-hop, there were no Nike or Adidas: there were few logos, multinational brands, or advertising campaigns — at least until Vivienne Westwood found success (or sold out?).

Siouxsie Sioux’s make-up — pale powder skin, dark lips, and thick eye shadow — has the look of a death mask. Punks often used such a look as part of an intellectual and aesthetic project to reflect back upon Western societies what they perceived to be the social sickness in oppressive systems of labor, exploitation, cleanliness, gender, and power. Unlike hip-hop, punk was seldom concerned with a vital and life-affirming alternative to mainstream Western culture. Sickness, decline, and crisis, crucial punk motifs, seemed endemic in a British state that was facing tremendous social, political, and economic uncertainty. Britain in the 1970’s had become almost trite as a political image, such are and were its uses, from Margaret Thatcher to Tony Blair, in portraying a declining United Kingdom that was falling behind its European neighbors in terms of economic growth and was veering inexorably towards a cataclysmic crisis. The £2.3 billion loan from the IMF in 1976, strikes, high inflation, weak growth, a run on the pound, escalating oil prices, Harold Wilson’s resignation, and the Winter of Discontent have become motifs synonymous both with Britain’s post-war decline and, to many, symbols of a British state ungovernable from the left. As the historian Andy Beckett writes, punk was a “cultural consequence of this mid-seventies unease and volatility.”

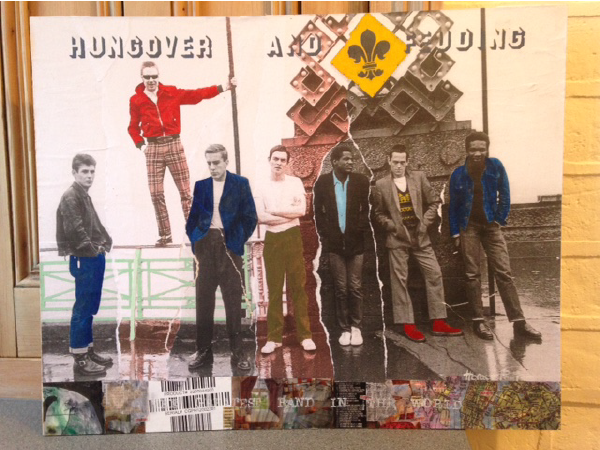

The mash-up always had more resonance in the sampling and mixing of hip-hop than in the amateurish three-chord stabs of punk rock. In the editing, something is lost. Students at Chelsea College of Arts were given the opportunity to interpret Beckman’s famous photograph of the Islington Twins from 1981 as the pieces are displayed in an adjacent room. One piece has red text daubed over the unaltered original image, a slightly obvious but nonetheless powerful moment of protest. Turning against the “neo-colonial gaze” which forces the criticism and denunciation of black cultures, the artist refuses to compare the two largely disparate movements. It is not unlike punk’s sense of irony that the act against such an imposition is evidently both protest and collaboration. It hangs neatly in the gallery, neither greatly out of place nor blandly submissive.

Don Letts, the promoter, DJ, and director who is key associate of the Punk London program, provides a quote which is stuck to the wall in a garish typeface. “Hip hop,” he says, “is black punk rock.” The attitude of punk, the “irrepressible attitude,” as Beckman called it in 2013, “brought an anti-establishment raw freshness to music, art and style. It was about change, the idea that people should question authority and do it for themselves.” The desire to co-opt a punk-like attitude to other pursuits, be they commercial or otherwise, extends to hip-hop as it does to many urban youth cultures — and was hardly new in 1976. Several subcultures since, like goth, steampunk, and hipster cultures, have done this in different ways. The error is — as hinted at by that student — that we lose a sense of hip-hop’s distinct and irreducible meaning by defining it, as Letts does, according to punk, which was for the most part a predominantly white movement. Samy Alim pointed out in 2006 that hip-hop rejected “white English” as the principal and preferable form of speech, particularly resenting its dominion over the form of communication in the intellectual battlefields of race, power, and social justice.

But maybe punk was always about mash-ups, about reuse and borrowing — and selling on. And maybe it is not so much that punk or hip-hop sold out, but that they were both so much a part and product of consumer life in the capitalist economies of Britain and the US that it is hard to tell where the selling ends and the mark of authenticity begins — if it does. Both genres have always had tricky relationships with success and questions of authenticity remain wildly subjective. The Sex Pistols, for example, earned enormous financial success but are not usually considered to have become traitors to the movement, despite Johnny Rotten’s attempts to napalm his credibility (if he cares about such things) in TV adverts for butter. For both punk and hip-hop, the contradiction of achievement and authenticity powerfully impact on their cultural legacy. A mash-up, indeed. •