I wound up hiking Mt. Brandon by accident. But it is an accident in the same way a traveler stumbles on ruins he didn’t know he was looking for. On Ireland’s Dingle Peninsula, they say you don’t get lost, you discover. And wherever you go, someone has been there before, walking.

So it was with me. While meandering along Slea Head Drive, stopping to take in the coastal views and ruins, I passed the sign for Mt. Brandon. It was late afternoon, still lots of daylight left. No need to return to Dingle just yet. So I turned around and followed the sign to the foot of the mountain.

All day I saw it looming over the peninsula, snow on its flanks, peak in the clouds, a presence. At the trailhead, the gentle slope looked enticing. I could start walking up the trail right now, I thought, the way people have done for hundreds of years.

•

I came to Dingle because of a book I read many years ago. Honey from Stone: A Naturalist’s Search for God, by Chet Raymo. In eight essays, named for the canonical hours, the author tries to reconcile the many evidences of historical faith on the peninsula with the findings of modern science. He looks deep into geological time on the Dingle coastline, ponders early Christian and pre-Christian ruins, tells the tales of the land, and goes stargazing. Through it all, he walks and walks, and these meditative hikes stayed with me.

I knew about Raymo’s writing from his previous book, The Soul of the Night: An Astronomical Pilgrimage, a heady mix of creation myths, poetry, and cosmology. I discovered it during my undergraduate studies in physics and astronomy, and it provided a lyrical antidote to my equation-filled courses. It was here I first learned that I wanted to read more from Rilke and Roethke, here that comets, star clusters, and quasars came alive among the constellations, and here that I got a taste of the big questions in cosmology: How did the universe begin? What is it made of? How will it end? The book was a quest for our place in the universe, and my young mind took to it like a sponge.

•

The trailhead is at the end of The Saint’s Road, an 18-kilometer path that winds through the peninsula’s various ecclesiastical sites, including the Gallarus Oratory and Kilmalkedar Church. I came upon parts of the route in the car, but pilgrims have been walking it since before the sixth century. Though I’m not a pilgrim, the idea of hiking such an ancient trail appeals to me.

But it’s late afternoon, too late to begin the hike. Yet I linger. I hear a few birds calling, a faint murmur of a stream rushing under a stone bridge beside a grotto dedicated to the Virgin Mary. A sloped sheep-meadow surrounds the small parking area. It is early March and though few tourists are about, another man, in his 70s, has found his way here. While his wife waits in the car, we spend a moment admiring the sign. Written in English and Gaelic, it shows a monk with a walking staff, above a Celtic cross and map. The sign encourages us to “Walk in the footsteps of saints.”

I ask if he has ever hiked the mountain. “Many times,” he says. I suggest that it probably takes two or three hours to hike to the summit. He agrees, and with characteristic Irish wit tells me a tale of a local elite hiker. This man was so fast that he bought his friend two pints in the village pub and hiked up and down the mountain before his friend finished the beer.

•

Around the time I read Raymo’s Soul of the Night, I met an amateur astronomer named Lucian and we became good friends. Lucian was a Franciscan monk, much older than me, but had a childlike sense of wonder and curiosity. One of his favorite words was “Gee!” When I wanted a break from my studies, I’d drive out to his Mount St. Francis, outside Cochrane, Alberta, just half an hour from where I lived in Calgary, and we’d stargaze until well after midnight. He had an 11-inch Celestron and was regularly pushing the limits of its abilities as we scoped faint nebulae and distant galaxies. He called himself Lamplighter, after the character in The Little Prince, who lit lamps in the evening on his small planet and put them out again in the morning.

•

In the morning, I drive back to the trailhead and set off. After crossing the bridge, the trail becomes a track partially filled with snow from last week’s late winter storm. The sky is mostly clear and the sun bright, but the whitened peak of Mt. Brandon is hidden in clouds. After crossing over the stone bridge, I pass through a gate and begin my ascent. I don’t usually hike solo unless I’m traveling, so already it feels like an adventure; I’m buoyed by a sense of awe and thoughts of discovery.

The trail soon peels off the track and I climb up the wet, grassy slope, following a series of white posts alongside a ravine. With each step, the view improves and I spend as much time walking backwards, trying to take it in, as walking forward. I can see Smerwick Harbor to the north, the Blasket Islands to the west, and try to pick out Clogher Beach, also to the west, where I went on a heart-pumping cliff-top hike the day before. With a few more steps I can see Skellig Michael, or Great Skellig, off the south-west coast, the site of an early Irish monastery.

From the shore, Skellig Michael is a crag that juts out of the ocean — a home for birds. I’ve become obsessed with it since first seeing it off the coast of Kerry, two days earlier: from Valentia Island, the cliffs at Portmagee, and the beach at St. Finian’s Bay. Skellig Michael became an iceberg that, once seen, floats in and out of the imagination for days or weeks afterward.

The name roils in my mind. Skellig, for steep rock, in Gaelic, but in English I think: bare bones, barren, skeletal. A place to endure the dark night of the soul, where the faith was stripped down to its core, where one has only the wind and waves for company. Even today it still harrows; boats only land when the sea is calm, and tourists have died from misplaced steps on the climb up.

According to a film I watched at a tourist center on Valentia Island, the monastery was active for more than half a millennium, from about the sixth or seventh century, till the 12th, when even a generation or two would have been an achievement. The monks constructed stone “beehive” cells high above the lashing sea. They must have lived on bird eggs, fish, and rain water. Why would they seclude themselves in such a harsh place? How did they spend their days? How did they live in such confined spaces? There are answers to these questions — to devote their lives to prayer while suffering extreme physical hardships, to be closer to God. But these answers don’t satisfy. I don’t understand the intensity of that faith.

Yesterday on Slea Head Drive, before stumbling on the trailhead, I stopped at the beehive huts at Fahan. They were slabs of stone piled into walls that enclosed small domiciles. I suppose two or three families would have huddled together in the small living spaces. If nothing else, they were sheltered from the wind that blew incessantly off the Atlantic. The remoteness of Skellig, with its swirling winds and dampness, would be enough to challenge any ascetic.

•

The Lamplighter was the one person the Little Prince met on his travels who he thought he could befriend, because only his concerns were beyond himself. Lucian made friends all over the world, corresponding with them about the night sky. When my studies took me away from Calgary, we began exchanging letters, first handwritten or typed, then moving to long letters composed at the computer. He wrote me that in retreats people had such short attention spans that they could barely follow one thought after another, that they were finding it harder to sit in quiet and had to be doing something all the time. This was ten years before smart phones.

On one Friday night, I attended one of his presentations before we went observing. He showed his own slides of flowers in bloom, set to classical music. He gave no narration or explanation, and I remember the feeling of looking closely at nature, at beauty, trying to see it for what it was, and sitting with the uncertain sensation of not knowing.

•

As I ascend Brandon, I’m amazed at the affinity I feel during this simple act of walking, thinking about the monks in their beehive cells. For the pilgrim, the view of Skellig would have been an inspirational sight — someone is praying there — like seeing a beautiful but unreachable cathedral that kindles one’s devotion. Long after it was abandoned, Skellig still has a presence.

An anonymous quote from the 12th century: “That I might see its heavy waves over the glittering ocean, as they chant a melody to their Father on their eternal course.”

Another: “Delighted I think it to be in the bosom of an isle, on the peak of a rock, that I might often see there the calm of the sea.”

Though it’s easy to romanticize the monk’s devotion, a poem from that era accentuates the severity of the monk’s life:

Cells that freeze

The thin pale monks upon their knees,

Bodies worn with rites austere

The falling tear – Heaven’s king loves these.

•

Lucian once wrote me about a presentation he was to give to amateur astronomers in Edmonton called, “Why Do We Observe?” He had to cancel the presentation for health reasons, but wrote that observing was a way to engage with the universe. He thought scientists and theologians both climbed the mountain of Truth, but from different sides. He sent me an old philosophical adage, “Nil in intellectu nisi prius in sensu.” Nothing in the mind unless first through the senses. As much a follower of Blake as of Christ, one letter ends, “Have you seen [the comet] Hyakutake yet? I was all set to go out at two am but it was overcast. Sure hope I don’t miss it.”

•

The land has its stories and often it summons a person a tell them. To the south I try to pick out landmarks on Kerry’s Iveragh Peninsula, where my own ancestors lived before the famine. Sometime in the Celtic period, long before the Skellig monastery was set up, the bard Amergin is said to have calmed the seas when he came ashore in Ballinskelligs Bay, in South Kerry (the same place that the Skellig monks built a new monastery when they abandoned the island). When he set foot on the land, the incantation he recited became known as Ireland’s first poem. I am the wind on the sea, he sang, I am the wave upon the land, I am the ocean’s roar.

I first read about Amergin in Honey from Stone and was smitten by his compelling voice, expansive and intimate, alive in a vast landscape. Reading his words is like having my own thoughts expressed in the midst of swirling wind. From the immensity of the ocean, he moves to the living world. I am the stag of seven battles. I am the hawk on the cliff. I am the dewdrop in sunlight. It’s a grand, mystical voice, the poetic “I” that communicates directly between hearts. I am all these things, and more.

•

Thanks to the recent, unusual snowfall, the path is wet with runoff. My shoes are soaked. I cross the ravine and continue up the grassy, boggy slopes. Soon, I pass a wooden cross on a pile of stones, and then ten minutes later another one. Markers for pilgrims, with large metallic Roman numerals on the crossbeam: The Way. The view opens wider—hills, meadows, islands, ocean — and at Station III, just as it becomes its most dramatic, it disappears. I’m in the clouds. Skellig is gone. The Blasket Islands and Smerwick Bay are gone. The view up the shoulder of the mountain is gone. I’m alone.

After the fifth station, I come upon a menhir, tall and coarse, like a stone finger pointing at the sky, atop a giant cairn. It is as if everyone who climbed Brandon over the centuries brought a stone from below to create a mound worthy of the mountain, and somehow the finger rose with each placed stone to remain at the top of the heap. It is unhewn and ancient, a relic from pre-history. Strange because it must pre-date the wooden crosses and have been placed by a different people for different reasons. An axis of the world, perhaps? A memorial? Even a sundial? Who knows the secrets of the unhewn dolmen? Amergin asks.

The Song of Amergin survived orally for many generations before finally being written down. And what of the Song of the Standing Stone? In all the comings and goings up the mountain, no one has passed along the tale of its origin.

•

Patches of snow lie scattered about the outcroppings of rock and I wonder if I’m equipped. “I think you’ll be fine,” my hostess Brenda said to me as I was leaving Rossbeigh to come to Dingle. The temperature is fine, several degrees above freezing, and despite my wet feet, I am not cold.

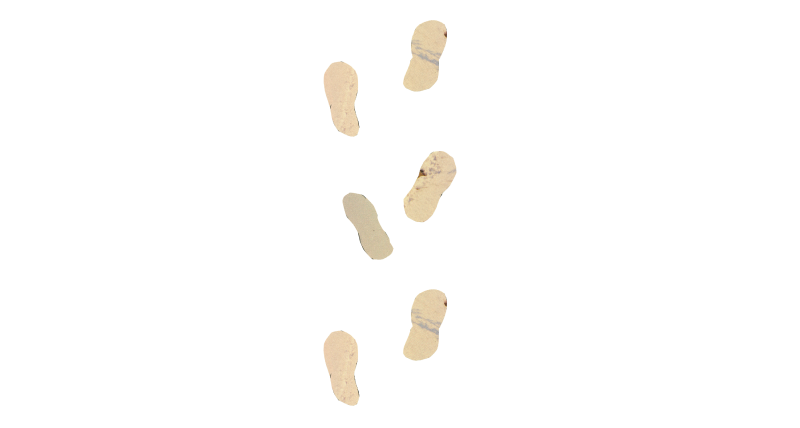

Before long, the patches join up and the snow thickens from ankle deep to foot deep. Here and there I see footprints in the snow, on the verge of disappearing. Someone has been here ahead of me. Maybe a day or two ago. Perhaps a solo traveler, like me, curious about what could be experienced on the hike. Or maybe a pilgrim who has climbed the trail many times before. Sometimes I walk in their footprints. Sometimes I create my own.

As I walk along the exposed ridge of Brandon, the wind picks up and I listen to my jacket ruffle, feeling like I’m going to be blown off the mountain. I fasten my hood, something I decide to be the best clothing invention ever. I flex my toes inside my wool socks to keep the blood moving.

•

Who smooths the path through the mountain?

Who speaks the age of the moon?

Who has been where the sun sleeps?

•

I stop. I’ve been hiking too fast and am out of breath. I had a rush of energy, a spontaneous flurry of excitement about being hidden in the clouds, alone on this mountaintop, and leapt from stone to stone, over the snow. Now it has caught up to me. There’s no place to take shelter and catch my breath. All I can do is stand still and let the wind blast all round. Perhaps I thought I was closer to the top; I’m not even at the seventh station yet.

I fear I’m not prepared for the conditions and I think about the stories I’ve read in Appalachia Journal, in the “Accidents” column. Tales of experienced hikers beset by harsh weather, and inexperienced hikers making foolish mistakes. I’m alone on a mountain I don’t know. I don’t even have a map. It’s just me and Brandon.

•

In Honey from Stone, Raymo writes of knowledge as an island in a sea of mystery; as the island grows, so too does the shoreline where they intersect. Late in the book, he discusses the night sky above Dingle and quotes Julian of Norwich, who asks, “What is the use of praying if God does not answer?” To this, Raymo replies that God answers in starlight. Ultimately, despite the promise of the subtitle, the only god he finds is in metaphor, something that disappointed me when I first read the book.

•

I am the lake on the plain.

I am the meaning of the poem.

I am the point of the spear.

I am the god that makes fire in the head.

•

I used to believe we all had a soul, and that this soul was the breath of God. I liked the poetry of the idea, that we all had a spark of the divine. And I looked for ways to validate it — in books, in nature, in the music of Bach. But when Lucian died, I suffered a crisis of faith. Lucian spent his life in service to his faith and to God, and on occasion he told me about the travails of such a life. Yet ever the Lamplighter, he performed his office with dedication and diligence.

When I found out he had died a painful death, from something like an extended heart attack, it shook me. I became angry at God. I couldn’t understand how such a generous, loving man who devoted his entire life to the Church, could be allowed to suffer so much. It made no sense to me, in the same way that Ivan Karamazov condemns a God who would allow innocent children to suffer. Lucian would have assured me that free will forbade God from interfering with the world. But that didn’t satisfy. I could accept that there are mysteries in life and death, and even a God who worked in mysterious ways, but this felt cruel to me.

Sometime later, I began to wonder when the soul entered the body. I realized I could find no satisfactory answer. Neither at conception nor at birth rang true for me. Did the soul somehow propagate from parent to child through the ages, through the eons and branches of evolutionary history? No, that didn’t seem right. Maybe, I decided, the only soul was metaphorical. There was no divine inside, or outside. My search was over.

Living in a universe without God is perhaps more frightening than living in one where God exists. One loses the comforts of an abiding presence, mute as it may be. Yet it forces a dramatic conclusion: it is to ourselves, with our own fire in our heads and in our hearts, who we must answer to.

•

At the eighth station, the wind is at its fiercest and I wonder if I’ll make it. Maybe turning back is a better option? I just wanted to go for a hike, I tell myself, it doesn’t have to be to the top. No one will fault me if I turn around.

Last month I read about Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition to the South Pole, turning back to avoid starvation when he was so close. He became a hero for his decision, for saving the lives of his crew.

Uncertainty. I’m not in a life-threatening situation, it’s merely unfamiliarity. I’m in the clouds and can barely see the next marker. I wasn’t counting on so much snow at the top — this is Ireland, after all. Is there an avalanche danger? I’m pretty sure there are too many rock outcroppings for that. I remember the forecast for the afternoon: partly sunny. Though mountains can create their own weather, I’m betting on no surprises: no freak snow squalls, no hailstorm like the one I saw yesterday on Slea Head Drive after visiting Gallarus. Nothing that will put me in the “Accidents” column. Just wind and cloud. Even Brenda’s voice reassures me: I think you’ll be fine.

•

The Gallarus Oratory was a revelation. An eighth century stone chapel built like an overturned boat. Cut from the nearly half billion-year-old Dingle Beds, each stone so snug against the next that the structure is still waterproof a millennium later. With the layers corbelled, the walls curve inwards till they meet 16 feet above the ground. A small, arched window gives a glimpse of Mt. Brandon in the east. The elegance of the structure is as compelling as the darkness inside. Seamus Heaney called it, “A core of old dark walled up with stone.”

The darkness is broken by a shaft of light inching in from the doorway. I was struck by the intimacy of the space. It’s a place for the faithful to have a private communion with their god “under the black weight of their own breathing,” a place for pilgrims to meditate on their journey on the Saint’s Road. Like a pilgrim, I wandered in and out of the darkness.

•

“Build a cathedral in your heart,” I once heard a minister say in the Nevada desert. We were a motley congregation, divorced from organized religion, wrapped in scarves and hats for protection against the dust and relentless sun. But I liked the idea of having so much space and light inside the heart, a place large enough to allow questions of faith to float about.

Gallarus is like an anti-cathedral, able to hold only a column of light in its darkness. The idea of building something like that inside spooks me; I have enough darkness already. Perhaps the point was to be inside, as Heaney writes, “in the eye of their King,” and then to come out again into the light, where “the sea [was] a censer and the grass a flame.”

•

After a steady trudge through the wind and snow up Brandon’s shoulder, an astonishing thing occurs: the trail veers to the south, into the leeward side of the mountain. and the wind drops. I can see a faint sun trying to break through the clouds. Near Station IX, I check the time. It has only been two hours, but I feel like I’ve walked through centuries. I stop for a sandwich. There isn’t much to see — a few rocks jut out of the snow. The next marker is barely visible in the cloud. The summit is still hidden. But the sudden calm penetrates me the same way it did at the trailhead the day before. I can’t believe how my fortunes have changed and I’m feeling an extraordinary happiness to be in this misty, other-worldly place. Now, for the first time, I know I can make it to the top.

•

In a subsequent book about Dingle, Climbing Brandon: Science and Faith on Ireland’s Holy Mountain, Chet Raymo relates a story of folk hero Finn McCool. One day Finn asks his followers, “What is the finest music in the world?” They suggest a cuckoo calling from a hedge, a spear ringing off a shield, the baying of a pack of hounds, the laughter of a gleeful girl. “All good music,” agrees Finn. “What is best?” they ask. Finn answers, “The music of what happens.”

How should one interpret Finn’s enigmatic reply? That all is ordained and things are unfolding as they should? Or that in being present one can hear the surroundings singing out? This is my preference. We can conduct our own symphonies only if we pay attention.

•

I’ve lost the footprints. The white markers are half-submerged in the snow. White on white. Two steps ankle-deep, two steps knee-deep. Occasionally, there is a spot void of snow and I glimpse what could be a trail. Someone has trod here before.

At Station X, the three-foot-tall pile of rocks that supports the cross is covered in snow. Same at Station XI. I zig-zag up through the white. Lucian once told me that he detected a restless spirit in me. It’s something I have taken solace in. But what am I looking for?

•

I’ve blanked on how many stations there are. I trudge past Station XII, what I thought would be the last station, with no summit in sight. At Station XIII, the cross is encased in so much snow and ice it looks like it hasn’t seen a sunny day in a thousand years.

For a moment I fear there are perhaps XXV or XXX stations and I might never reach the summit. I think of Machado: Traveler, there is no road, the road is your traveling . . .

•

In his book on the Dingle peninsula, Steve MacDonogh describes the pilgrimage to the summit as “important, known for many centuries throughout Ireland and probably in Europe.” St. Brendan is said to have climbed the mountain in the sixth century, before setting off on his seven-year voyage to the Island of the Blessed. Pilgrims would follow the Saint’s Road to the Gallarus Oratory, then to the church Kilmalkedar, named for the local saint Maolceadair, and finally up the mountain. MacDonogh relates a legend attesting to the popularity of the pilgrimage: when a priest arrived at the summit ahead of a line of pilgrims, he realized he’d forgotten his prayer book. Word was passed down the line to the last pilgrim, still leaving Kilmalkedar. So he collected the book and passed it on up the line to the priest at the summit.

Kilmalkedar used to be a pagan center — before St. Patrick came to Ireland in the fifth century — and one can see pagan stones in the churchyard, an indication that aspects of the Celtic religion were assimilated by Christianity rather than overthrown. The Christian pilgrimage was likely an adaptation of earlier pagan rituals, particularly Lughnasa, the festival of the harvest, celebrated in late July. People would gather for sacred rites, games, dancing, singing, and courtship. A bull would be sacrificed and the first corn cut. Such community and feasting on the flanks of Brandon would be a fine sight. The echo of these events, not just centuries but millennia old, is that the pilgrimage continues. For my part, I’m grateful for the solitude as I walk through time.

•

Station XIV is back on the ridge, and once again the wind batters me. Visibility is only a few meters.

I pick up the set of footprints again. Windswept, almost covered. I wonder how long mine will remain. At last, I can see a tall wooden cross on the summit. White veils of snow and ice fly frozen away from it. It has become a snow sculpture in the shape of a cross. In Gaelic, the summit is known as Barr an Turas, or “Top of the Journey.” I made it.

I edge past the cross and suddenly stop. The white snow underfoot gives way to a nebulous gray: a precipice. “The mountain is hazardous,” I read later in a guidebook, “has steep cliffs and is prone to sudden disorienting mists.” It is not the rounded summit I was expecting. Spooked, I shuffle away from the edge and resist exploring further. Whatever is up here — a holy well, a ruined oratory, penitential cairns, a pillar connected to another Finn McCool legend — is buried in the snow. If only it were clear — the view must be incredible. Above, a wispy silhouette of sun appears again and I try to will it through, to no avail.

The wind screams, the clouds pass through me, and strangely I’m ecstatic, marooned in a world of whiteness on top of the mountain. It might as well be the top of the world.

•

I bound down the mountain. Giant steps into the snow, as if walking on the moon.

At Station III, I’m out of the clouds again. Skellig drifts back into view. The Blasket Islands. Smerwick Harbour. Even the sun comes out enough for me to take a break next to the ravine. I sit on a rock, take off my shoes and socks, and lay them out to dry. At this lower altitude, the wind has dropped to a gentle breeze. The sun is warm. I hear the whisper of the stream again. The view stretches out to where the sun sets. The music happens. •

Graphics created by Emily Anderson.