Elizabeth Bishop’s friend, fellow poet, and favorite critic Randall Jarrell often centered a favorable review on a list the poems he most admired from that poet’s work. Many an anthologist has borrowed liberally from these carefully chosen Jarrellian lists. Jarrell, perhaps the most demanding and certainly the most prescient critic of his age, liked Bishop’s poetry very much indeed. And in a 1955 survey of “The Year In Poetry” for Harper’s, he cites 31 titles that “I hope you’ll read for yourself” from Bishop’s recently published collection Poems, which would soon go on to win the Pulitzer Prize. Conceding helplessly that “This is a ridiculously long list,” Jarrell adds that, “if I went back over it, I’d make it longer.”

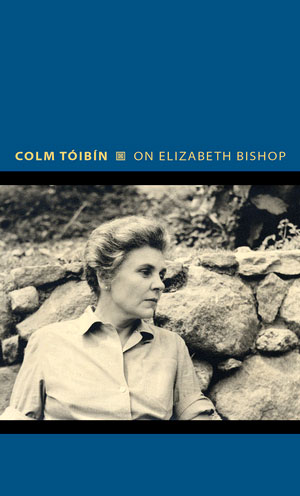

On Elizabeth Bishop by the distinguished Irish novelist Colm Tóibín is the most recent volume in Princeton University Press’s intriguing Writers on Writers series. It is constructed as a series of 13 brief essays, each offering its own distinctive meditation on an aspect of Bishop’s work — and usually pairing her life and work with a person or place that mattered to her. The effect resembles an ongoing conversation with Bishop, as well as with many of Bishop’s elders, contemporaries, and juniors in the world of poetry. It is, at the same time, a conversation with the reader. Tóibín himself frequently brings into the conversation his own affinities with Bishop as a person and a writer, even as he explores her affinities with others. Tóibín’s working method, with its conversational and nearly stand-alone chapters, seems to invite a reviewer to follow Jarrell’s list-making method. So here is my list of favorites among Tóibín’s colloquies, many of whose titles evoke famous catch-phrases from Bishop’s writing, essays that I hope you’ll read for yourselves: “In the Village,” “The Art of Losing,” “Grief and Reason,” “The Little that We Get for Free,” “The Bartók Bird,” “Efforts of Affection,” and (my favorite of them all) the lyrical concluding essay “North Atlantic Light.”

Read It

On Elizabeth Bishop by Colm Tóibín. Available now from Princeton University Press.

Let’s look more closely at just four points of interest along the way. The first of these, “In the Village,” provides a reflection on a place that served as an emotional center of Bishop’s conspicuously decentered inner life. That place is Great Village, Nova Scotia, where Bishop’s mother Gertrude suffered a psychological breakdown when the poet was five. Bishop had already lost her father to Bright’s Disease when she was eight months old. When Gertrude, who had never recovered from the loss of her husband, was placed in a mental institution four years later, the child Elizabeth never saw her mother again. As Tóibín notes, “The modest house” where her mother’s breakdown occurred “still stands in a strange coastal flatness, with deep inlets all around.” Tóibín notes both the Vermeer-like topography and peculiarly beautiful light of Great Village, characteristics also found in Bishop’s work. In fact, as Tóibín notes, when a Jarrell review described Bishop’s poems has having often the qualities of a Vermeer, Bishop wrote back, “It has been one of my dreams that someday someone would think of Vermeer, without my saying it first, so now I think I can die in a fairly peaceful frame of mind.” In this essay, Tóibín links many of Bishop’s finest poems, including “The Moose,” “Sestina,” “Crusoe in England,” “Poem,” and “The End of March” — as well as, of course, her luminous short story “In the Village” — to emotional and visual sources in this crucial native place, the first, by the way, of the places that Bishop loved but of which she was not a citizen.

Much of Tóibín’s fascination with Bishop as a poet and a person stems from the way her work discloses and withholds emotion. In “The Art of Losing,” Tóibín discloses one major reason why Bishop’s poetic modality holds such resonance for him, resonance that arises from the analogies Tóibín discovers between his own native town of Enniscorthy in southeastern Ireland and Bishop’s Great Village. More importantly, he also recognizes echoes linking the way his family dealt with the early death of his father, who died after a brain operation when Tóibín was 12, and the way Bishop’s family dealt with her early loss of both father and mother. In each case the family dealt with the loss by not talking about it — or even, in any overt way, acknowledging that a loss had actually occurred. As a result, according to Tóibín, “I have a close relationship with silence, with things withheld, things known and not said.” It was not long after the loss of his father, according to Tóibín, that “I discovered poetry.” By the time Tóibín settled in Barcelona and began his career as a writer, Bishop’s Selected Poems had become for him “a treasured book,” in substantial part because of Bishop’s own close relationship with silence and her consummate art in handling things powerfully felt and known, but not said.

More on Bishop

Thomas Travisano explores Elizabeth Bishop through the eyes of James Merrill, her protege and friend… »

Tóibín’s most extended and unexpected colloquy may be found in the linked pair of essays “Grief and Reason” and “The Little that We Get for Free.” Here he explores connections between Bishop and the English poet Thom Gunn. Few, if any, critics have previously linked these two poets, but Tóibín makes a convincing case for reading them in parallel. Bishop and Gunn became good though not intimate friends after they met in San Francisco, where Bishop had briefly settled after her long sojourn in Brazil and where Gunn had previously settled for good. Tóibín reads Gunn, too, as a poet who had “dealt with solitude,” in part because of his mother’s death by suicide when the English poet was just a boy. In each poet he finds what he calls “grief masked by reason, grief and reason battling it out.”

My favorite of these colloquies, as mentioned, is the eloquent coda, “North Atlantic Light.” In this brief chapter, almost a prose poem, Tóibín explore the resonance for him of the Irish coastal village of Wexford, where he used to go in the summers with his family when his father was still alive, and where he now sits writing. Echoing Bishop’s “Poem” — the central focus of this valedictory meditation — Tóibín suggests that on “this small stretch of coast, this literal small backwater,” he finds the place “where I feel closest to something I know, or remember, or wish to see again, write about again.” In what Bishop might have called “the queer light” shining down upon this Irish village “of a temperature impossible to record in thermometers,” Tóibín finds a final and compelling point of connection between his own personal and artistic worlds and the personal and artistic worlds of Elizabeth Bishop. •

Book cover courtesy of Princeton University Press. Photo by Verne Equinox via Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons).