Is there a place on Earth where people had to shovel snow from their roofs during winter every day? Where they lived like moles under the snow? Where there was never a question whether or not there would be snow at the end of the year?

In fact, there was: near the western coast of the Japanese peninsula, where weather conditions have always been markedly different from the coast of this country facing the Pacific Ocean. The seasonal winds coming from Siberia pick up evaporation from the Sea of Japan which helps to increase their humidity. Clouds form and as they pass the high mountains they cool and transform into masses of snow that almost defy description. Snow begins to fall towards the end of October.

Read It

Snow Country Tales by Suzuki Bokushi

Before the arrival of modern technology, this region was really in a world of its own: a microcosm of a winter wonderland, where the logic of winter was played out to the extreme. We know about all of this thanks to the report of Suzuki Bokushi, a Japanese merchant who knew the Niigata region (formerly the historical region of Echigo) in the 1830’s. More than a mere travel report, it is a participant-observer ethnographic study in the full sense, even before the scientific discipline of ethnography was properly established. Bokushi’s book was published (in Japanese) in 1835 as Hokuetsu Seppu, or Snow Country Tales. As he writes, he was actually buried under the snow when he began to compose his book.

The houses in the region were built to resist the enormous masses of snow falling during the winter. The roofs had boards that were both thicker and broader than those used in other parts of Japan. Additional wooden supports placed over the boards and stones helped to protect the roofs from winds. The snow, powdery in form and easily blown into drifts of six to ten feet in a single day, had to be shoveled from the roof immediately after the snowfall because otherwise entrances would have been blocked and the inhabitants would have found themselves hopelessly buried. The high windows also had to be cleared to allow some light to come in, especially for the New Year’s festivities. But where to put the snow? “It is packed hastily onto the elevated snow pathways that run between the houses, higher than their roofs in many places, and naturally many slippery dangerous spots are bound to appear.”

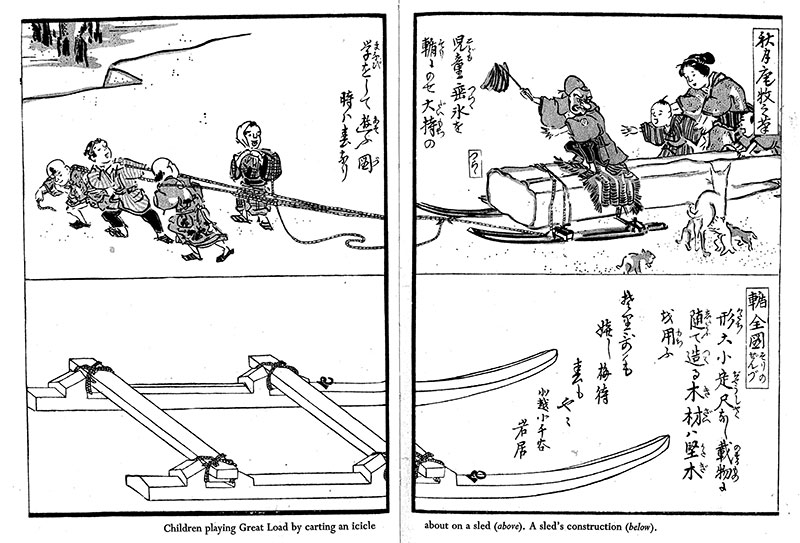

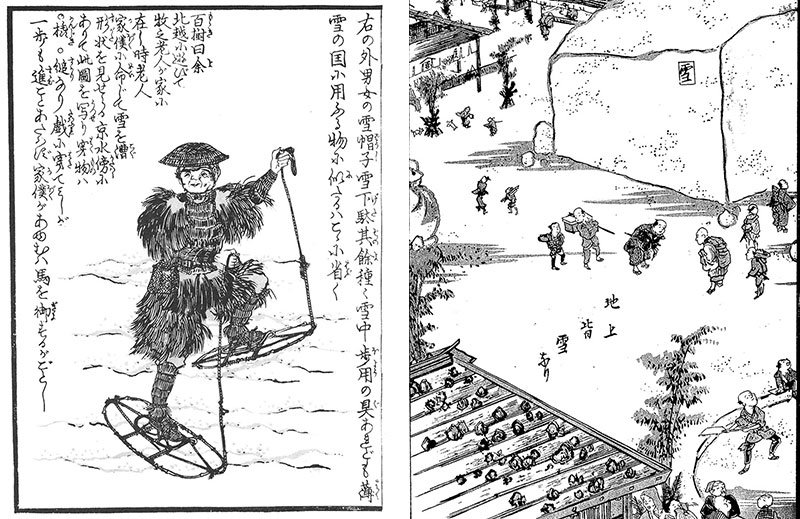

The inhabitants had a whole range of artfully designed equipment at their disposal: different kinds of snowshoes for walking through the soft snow, made from the twigs of the jagara tree, snow boots, snow headgear, and snow vests or chest covers made from bark that had proven effective in protecting farmers from the snow blowing towards them. Sleds could not be used before March or April, because only then would it be hard enough not to sink into. Horses were of no use at all under these conditions.

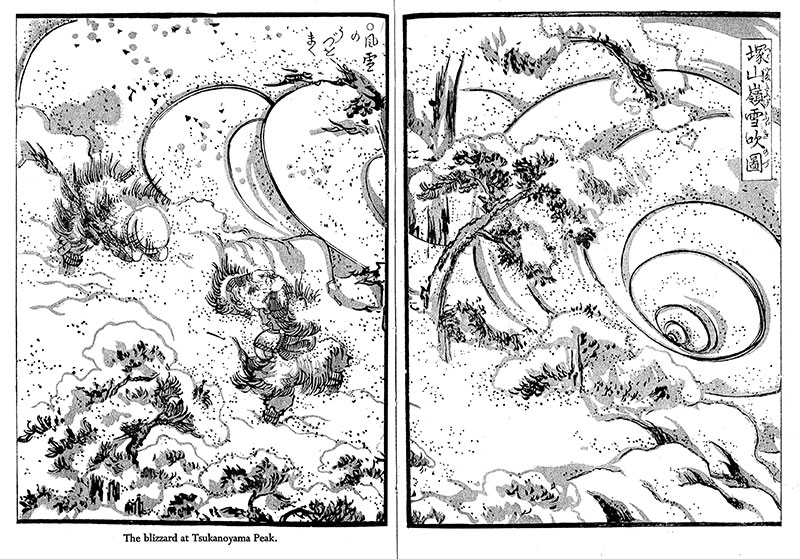

Blizzards, whirlwinds, and snow twisters, at times likened in ancient Japanese poetry to the scattering of cherry blossoms, were known to claim many lives every year. Suzuki offers some advice here which, of course, is not to be taken literally:

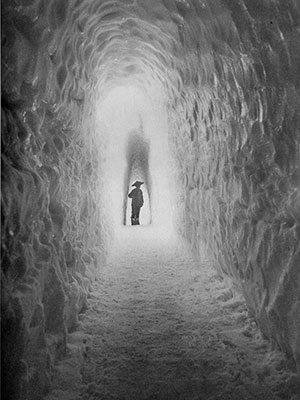

If you are caught in a blizzard, the best thing to do is dig a hole in the snow and crawl into it. In a very short time you will be covered with snow, and, surprisingly this is the warmer place to be. You can breathe and thus escape death.

Everything was quite different back then and people had to find a rhythm of their own. Since trees remained covered in the snow, the snow also served “as a natural platform to reach the treetops that normally they [could] only gaze up at” and people were able to cut the high branches as they pleased — at least there was no shortage of firewood whatsoever. Natural wonders abounded.

For half of the year people were entirely buried under the snow, and they only spent four months completely without it. “Early Summer Snow,” the headline of one of the many vignettes in this book, describes these circumstances. Plum trees did not blossom before April or even May. As late as in early June there were large chunks of ice on the fields that had to be sawed into blocks so they could be taken away to allow rice to be planted. Springtime also signified a return of daylight:

Now, at last, the rooms of our houses that have been dark since November grow gradually lighter, and we feel like a blind person who regains his sight.

While many stories presented in the book end in disaster of one sort of the other, it also testifies to the many joys of living in the snow. The difficult living conditions created a community or cohesion among the inhabitants that otherwise would not have been possible. Children played whatever games they wanted, whether the weather conditions were adverse or not. They had snowball contests and played badminton in the snow, using a shuttlecock made from a short stem of the deutzia stuffed with three pheasant tail-feathers and racquets improvised from the wooden shovels used to clear the snow-laden roofs. Young men and women joined in, others watched from their windows: one of the entertainments in the snow was that “everyone has a great laugh when the snow goes down the loser’s collar and into his breast.”

Winter did not even stop people from holding theater performances. The entire theater structure, including the stage, raised runway, dressing rooms, and stands was made of snow. “The heavens lend a helping hand in all this human endeavor, for each night that day’s work is frozen hard as stone. No matter how full the house becomes, the seating area is never in danger of collapsing.” Occasionally, the opening day had to be postponed when the spring snow continued to arrive. Actors, however, did not just still and wait: they went to the river to pray for clearer skies “by breaking through the ice and dousing themselves with the icy waters.”

Since Suzuki wrote his fascinating report, life in the region has changed dramatically. Until glass windows became widespread, people created them from elegant, stiff Japanese paper. Electricity, telephone, radio, cars, and iron stoves with chimneys have irrevocably altered life in Niigata as Rose Lesser — a native of Berlin who moved to Japan in 1929, discovered the book, and translated it into English — was able to observe.

The German filmmaker Ulrike Ottinger, known for a string of award-winning productions which navigate an unconventional line between fantastic fiction and no-less fantastic reality, has created a tribute to Suzuki’s book and the people he described in it with her 2011 film Unter Schnee (Under Snow). And there it is: high snows; the majestic landscape with its thunderous waterfalls and blustering winds; the strange ritual of throwing bridegrooms-to-be in the snow; long lines of colored crepe paper in the snow; Kabuki actors, with their faces made up, enacting dramas in the snow, hardly intelligible to the Western viewer. Different narrative layers overlap. There is traditional music. Time seems to stand still, the movie’s slow pace countering the quick editing of scenes prevalent in contemporary movies and television. Is this movie really a documentary? We are tempted to forget that this is a reenactment of past traditions and we are left with the question as to whether the children of Niigata have really done away with playing badminton in the snow or not. •