There’s a scene in Uzumaki, Junji Ito’s much-lauded horror series, that I think best exemplifies his particular style. The overarching story involves a secluded village in Japan whose residents become obsessed with spirals and usually meet grotesque and destructive ends as a result. In the third chapter, a scar on a teen girl’s forehead turns into a spiral black hole of sorts, eventually consuming her entire body. A horrific reveal shows the spiral hole extending back into her head, her right eye sitting gruesomely on the edge of her face. Then, in a series of smaller panels, the eye starts to roll back towards the vanishing point in the back of her skull.

It is, obviously, pretty horrific. It’s also very, very funny: a rimshot as we literally stare into the abyss, acknowledging the absurdity of the image while underscoring the gore.

This is one of Ito’s primary strengths: an ability to combine comedy and horror in a manner that does not subvert or destroy the dread, but instead enhances it. A growing number of works, comics and otherwise, have attempted to pivot back and forth along the uneasy border between laughter and fear — think of the “Too Many Cooks” video, or the work of the Wham City Comedy troupe — but Ito has been doing it longer and to much greater effect.

Ito began publishing manga in 1987 while working as a dental technician. He quickly rose to prominence, thanks mainly to his Tomie series, about a seemingly immortal young woman whose stunning beauty inspires men to murder. Drawing on both Eastern (manga-ka Kazuo Umezu) and western (H.P. Lovecraft) influences, Ito has since become one of the prominent horror manga artists around, and several of his works have been adapted to television and film.

And yet not much of Ito’s work has traditionally been available in the U.S., which is surprising considering both his extensive bibliography and how popular his work seems to be. Apart from a few (now long out-of-print) attempts at collecting his comics, the aforementioned Uzumaki and Gyo, a two-volume saga about monstrous zombie fish with robot legs, are the only two comics that have remained in print in North America. Perhaps that’s simply because since so much of his work is available for free on the internet (in what is known as “scanlation”), few publishers are willing to risk the expense of releasing material that serious fans have already read online. Such is the curse of piracy.

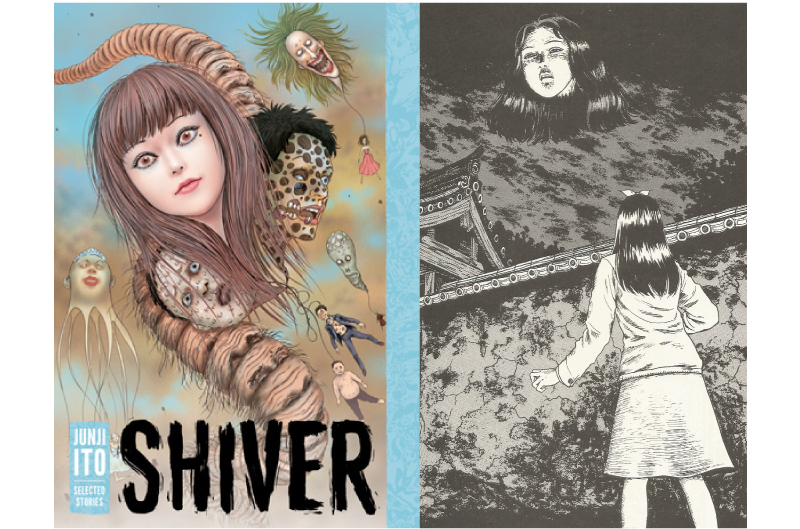

That’s changed in recent years, however. 2015 saw the release Fragments of Horror, a collection of recent stories, followed by a Tomie collection, Cat Diary: Yon & Mu (a foray into straightforward comedy), and Dissolving Classroom, another recent work. Now we have Shiver, a collection of nine short stories hand-picked by the author himself and presented with his notes and commentary. As such, it remains a pretty solid introduction to the artist and his worldview and a good entry point for the curious.

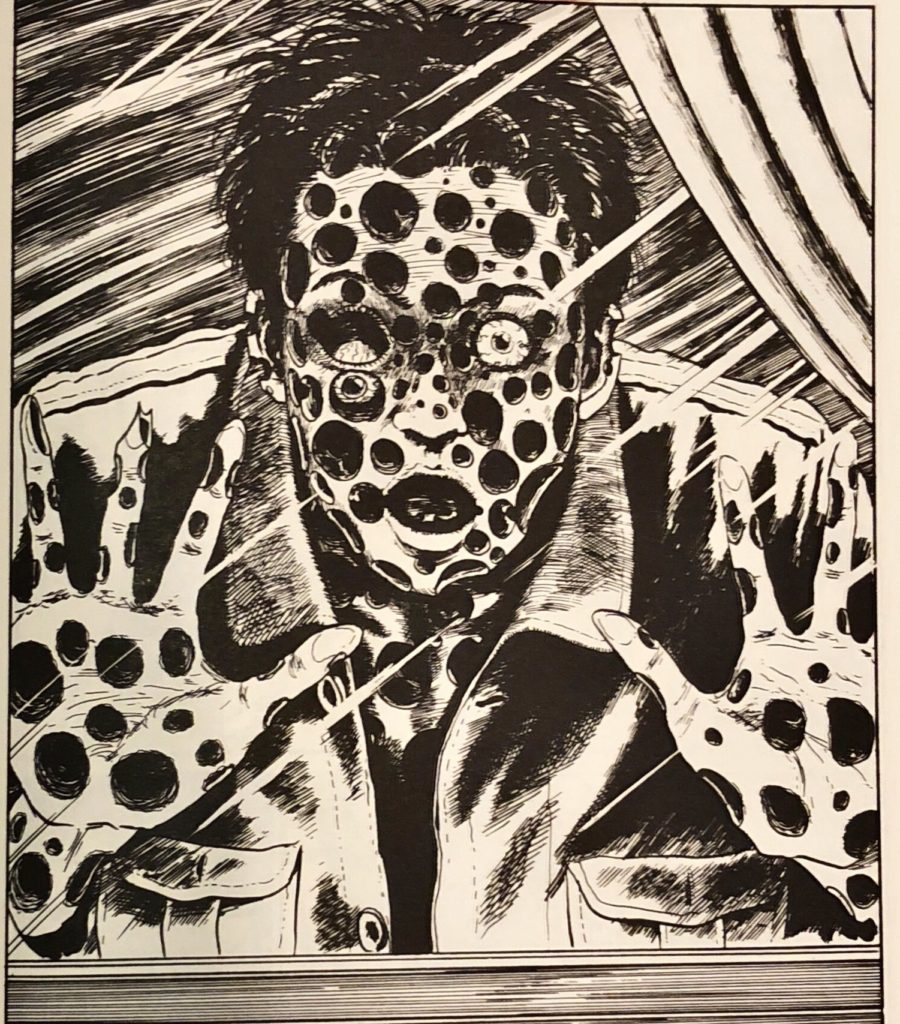

Ito’s universe is largely one of happenstance or, if you prefer, sheer bad luck. Unlike, say, in E.C. Comics, where the people who come a cropper of bloodthirsty ghoulies and ghastlies deserve everything that eventually happens to them, the folks in Ito’s stories rarely have it coming. The teen boy in Shiver’s title story doesn’t ask to have holes appear over his body ’til he looks like swiss cheese; he just picked up the wrong cursed object at the wrong time. The man in “Long Dream” whose dreamlife lasts eons while his body malforms and turns to dust didn’t request this particular ability, nor does the woman in “Honored Ancestors” seek out her horrible fate. Ito’s universe is a cold and uncaring one.

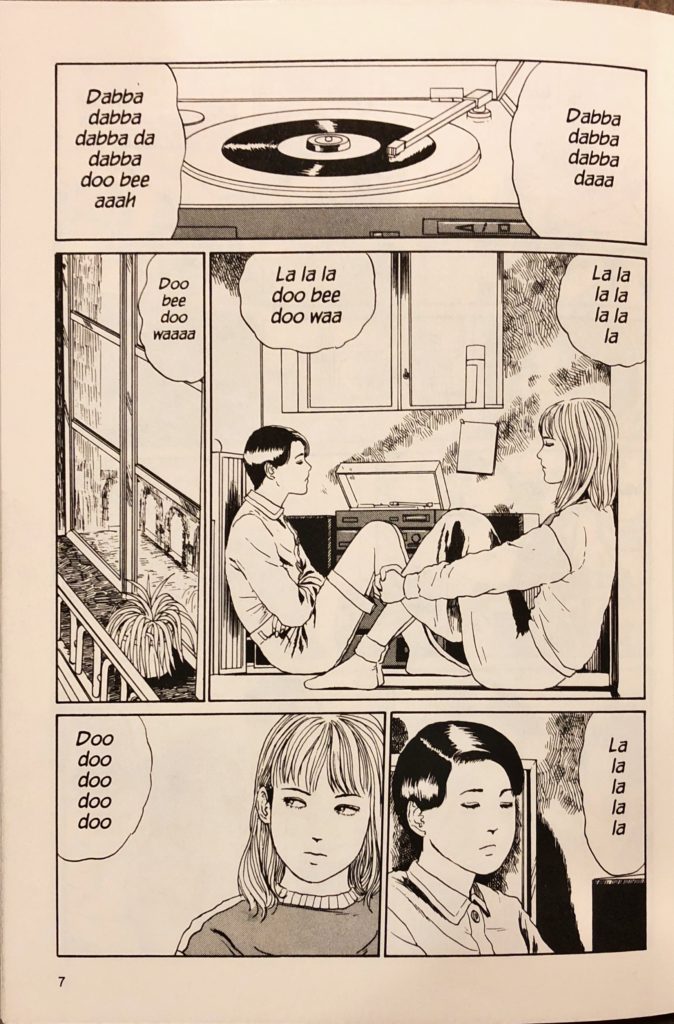

What Ito’s characters most frequently are is obsessed. Perhaps it’s an object, a person, or even just an abstract symbol (like the spirals in Uzumaki). Whatever the focus of their passion, Ito’s characters often find themselves in the full grip of mania, driven to self-destruction or worse. In “Used Record”, an odd recording of scat singing is so striking that a young woman kills her friend in order to possess it. In “Greased” (perhaps Ito’s most grotesque story to date), a young man growing up in a barbecue restaurant starts becoming obsessed with the grease that covers everything and begins drinking gallons of oil (it doesn’t do much for his skin).

Often this type of obsession revolves around lust, or perhaps an unhealthy fear of sex. In “Painter”, the one Tomie story in Shiver, an acclaimed artist becomes obsessed with the monstrous Tomie. He tries to paint her portrait, but the resulting likeness leads to murder and dismemberment. The terrifying creature in “Fashion Model” is a carnivorous glamour, um, girl, who does not take kindly to being left out of the spotlight. Ito clearly has a thing for monstrous women: He likes to touch on nerves surrounding cultural ideas of beauty, femininity, and coitus.

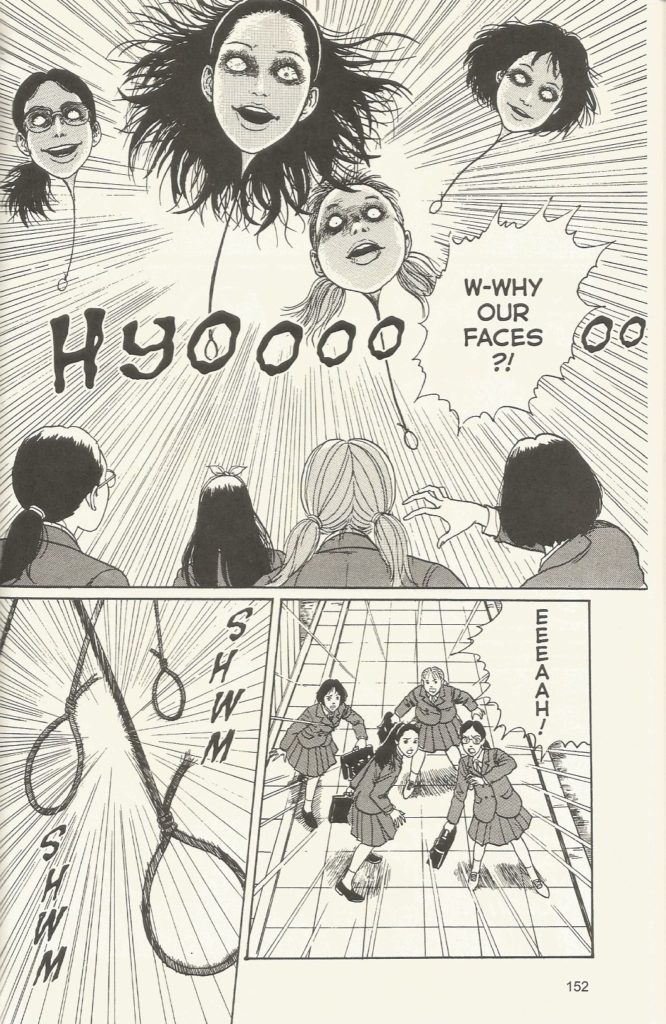

But while sex, body horror, and the randomness of fate are some of Ito’s big motifs, it’s his healthy appreciation for the absurd that I find the most noteworthy. Take the story “Hanging Blimp” for example. It’s an apocalyptic story where the end of humanity comes about not through zombies or disease but giant balloons that bear your and other people’s likeness on them. These creatures (if they can be called that) pick you up and hang you by their dangling string, should you be unlucky enough to come across them.

On description, this premise sounds ridiculous, but Ito completely sells the idea within the story’s short page count. He doesn’t make any attempt to explain why this is occurring or ferret out any logical inconsistencies. Like a bad dream, the horror simply is, nothing more. More to the point, Ito seems to instinctively understand that the premise is a little silly and rolls with it, letting the ludicrous aspects of his story come to the fore and using them to underscore the horror of the situation. At one point, a man tries to puncture one of the monstrous balloons with a crossbow. He succeeds, but as the balloon deflates, so does the head of the corresponding person, in both cartoonish and terrifying fashion. It’s this sort of absurd horror that makes “Hanging Blimp” one of the most unsettling stories in the collection.

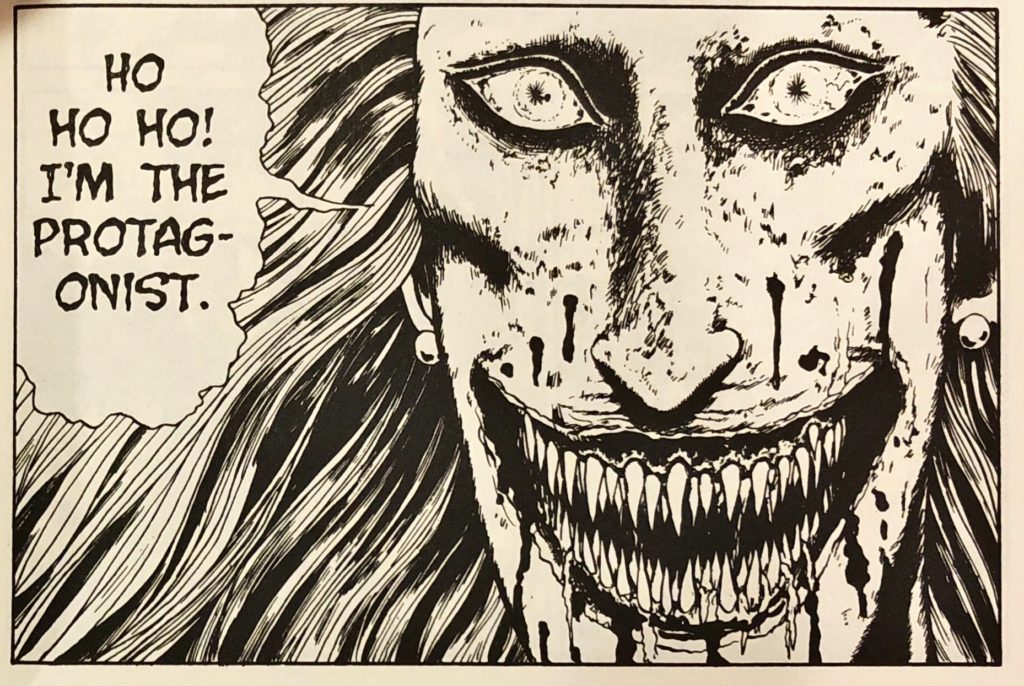

You can find humor in the other stories as well. There’s something about the titular creature in “Fashion Model,” for instance, popping up with blood running down her chin and exclaiming “Ho ho ho! I’m the protagonist,” to a group of horrified filmmakers that is both comical and frightening. Or in the way that the “honored ancestors” in that particular story pile snake-like atop their descendent’s head, urging him to find a mate (“Hurry up and catch that filly”).

And just in case you didn’t get it, there’s often a social theme in Ito’s horror stories. “Honored Ancestors” is a sly, stark condemnation of arranged marriages and familial pressure to produce an heir. “Greased,” at its core, is despair and generational resentment fueled by poverty.

Ito’s recent work — Dissolving Classroom, Fragments of Horror, and a final tale in Shiver that sees the return of our beloved model — isn’t as strong as his older material. That’s partly due to the fact that he’s switched from his more traditional ink-heavy, obsessive cross-hatching style to a somewhat lighter style using computer gradients. His stories feel less claustrophobic as a result. (Dissolving Classroom pushes harder into the humor arena, too, with a protagonist whose apologies are so over the top that they literally cause people’s brains to melt).

No doubt this switch saves Ito a lot of time and effort (carpal tunnel syndrome is a real thing among cartoonists), so let’s cut him some slack. There are plenty of Ito stories that deserve to be released in physical books rather than just floating around the interwebs, depriving their creator of funds. In the meantime, though, horror fans looking for mordant chuckles with their scares can start with Shiver. •

All images are copyright Junji Ito.