It’s unusual for anyone to wish they could be as cool as a cartoonist, but Julie Doucet is the rare exception to that rule. In her groundbreaking 1990s series, Dirty Plotte, Doucet delineated an aesthetic that was brazen, clever, funny, and broke taboos like they were cheap ceramic plates. Reading her comics, you could be excused for wishing you had an ounce of her fearlessness, at least when it came to putting ink on paper.

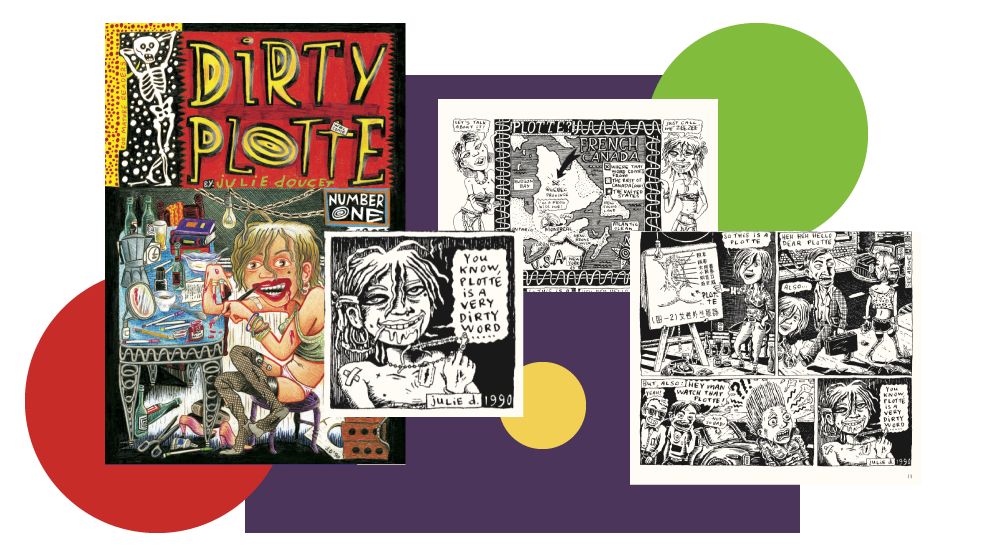

Now, all 12 issues of that seminal series have been collected in the rather massive The Complete Dirty Plotte, an impressive two-volume slipcase that also includes stories done for anthologies, essays, interviews, and other esoterica.

Doucet got her start in the heady “alternative” world of zines and mini-comics, where people, in the pre-Internet days, would photocopy or publish their musings in art in a small pamphlet or magazine and send it to folks through the mail. The initial attention she received with those early comics (as well as some appearances in notable anthologies like Weirdo) led to her getting picked up by Drawn and Quarterly, the first regular artist in their soon-to-be impressive stable (up till then they had been solely devoted to publishing a quarterly anthology).

Right from the get go Doucet made it clear she was taking no prisoners and offering no apologies. The title, she explains on the very first page of the very first issue, is a Quebecois slur for vagina (or a woman with loose morals). After a few examples of everyday usage, Doucet glares at us with a sultry look, drooling lips, and a razor blade necklace, saying, “You know, plotte is a very dirty word . . . ”

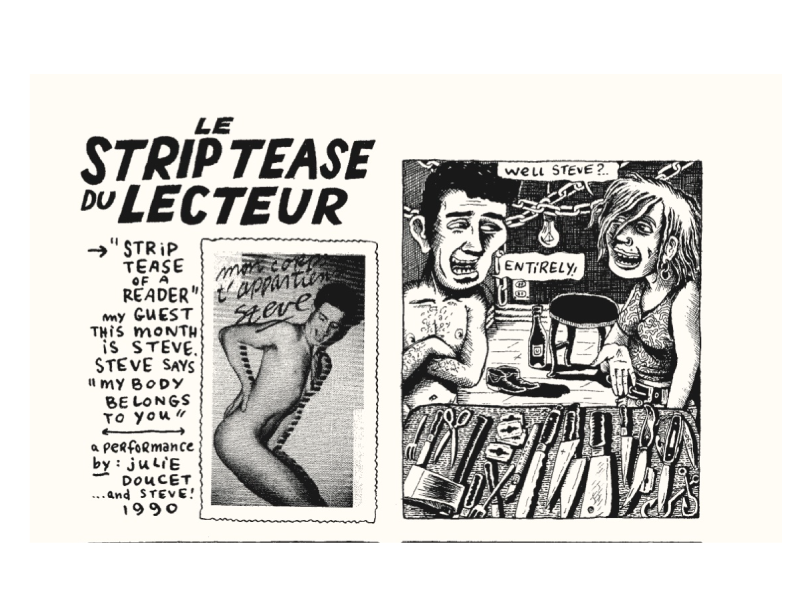

Other strips push boundaries even farther. One very early comic shows her performing a strip tease that ends with her ripping off her breasts and slicing up her midsection, as her dog and cat leap hungrily toward her entrails. Another has a stalker murdering a child and then letting his dog devour the body (“dog is truly man’s best friend”). In issue three, she takes a hatchet to a naked man, cuts his body with a razor blade, cuts off his penis, and then uses the bloody stump to write “fin” on the wall.

Many of these comics owe a good deal to the work of ’60s underground cartoonists like Robert Crumb and S. Clay Wilson. Where she decidedly separates from this pack, however, is through her focus on specific female concerns, especially menstruation. One famous story has her growing to Godzilla size when her period hits, literally flooding the streets with her menstrual blood. Another comic has her lying in bed and realizing she needs to change her tampon. She then magically levitates to the bathroom, successfully making it to the toilet in time.

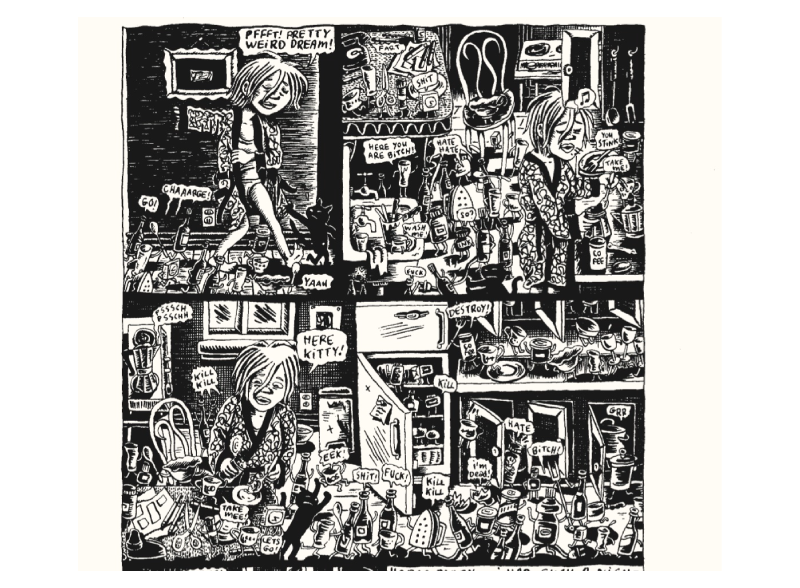

And yet despite the gore and excess, there is a comical playfulness to Doucet’s work that belies (but does not completely negate) those transgressive aspects. Her panels are always bustling with activity and clutter; every object on the street or in her apartment seems capable of coming to life (and does in one particular comic).

That sense of playfulness extends to her general amusement with the human body, particularly genitalia — chiefly male genitalia — which she finds especially hilarious. In one strip, a man introduces his penis, Pete, to the reader and shakes his fist, warning, “Don’t ever hurt him! Or else look out!” In the serialized story Monkey and the Living Dead, the title character (who is actually a humanoid cat), is comically obsessed with penises, though she seems to not really understand their actual biological purpose.

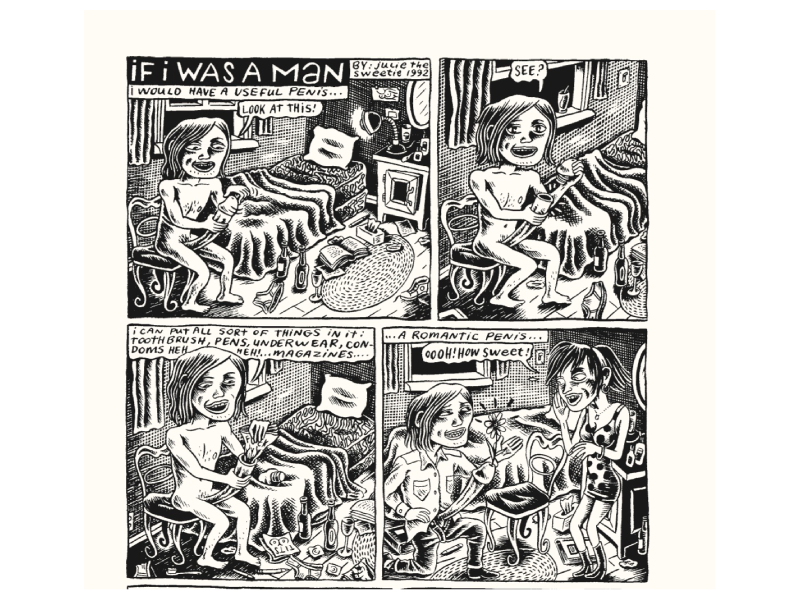

Doucet frequently crosses gender barriers herself in her stories, imagining herself as a man, envying the act of shaving or musing on the pros and cons of owning a penis (she names it “Mustang” and imagines being able to screw off the head like a bottle cap, so she can store magazines and other important items on the go). In The Double, Doucet comes across a spooky mirror, realizes she’s dreaming, and then turns herself into a man. She then brings her female mirror image through the mirror and proceeds to get busy.

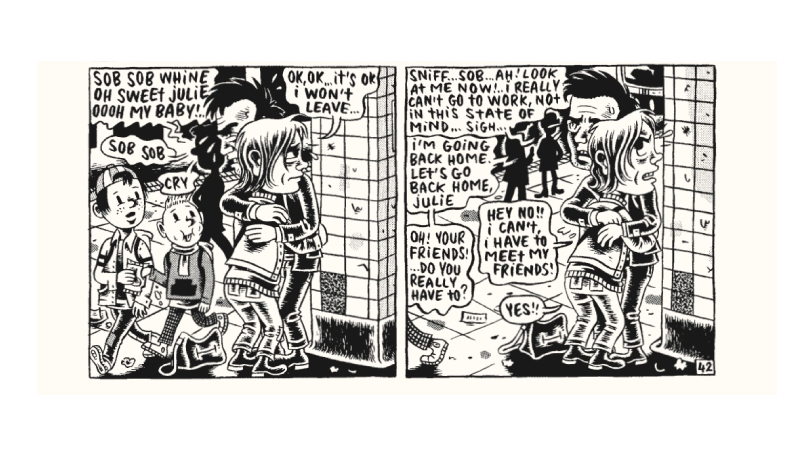

But if her attitude towards male anatomy is amused, her attitude towards men in general is decidedly less positive. The men in Doucet’s comics are shiftless and unreliable at best, malevolent and violent at worst. In one dream-based comic, a man attempts to cut her fingers off with a knife. In another, a man injects drugs into her eyeball. In a third, an odd-looking figure offers her a croissant, conveniently tucked into his underwear.

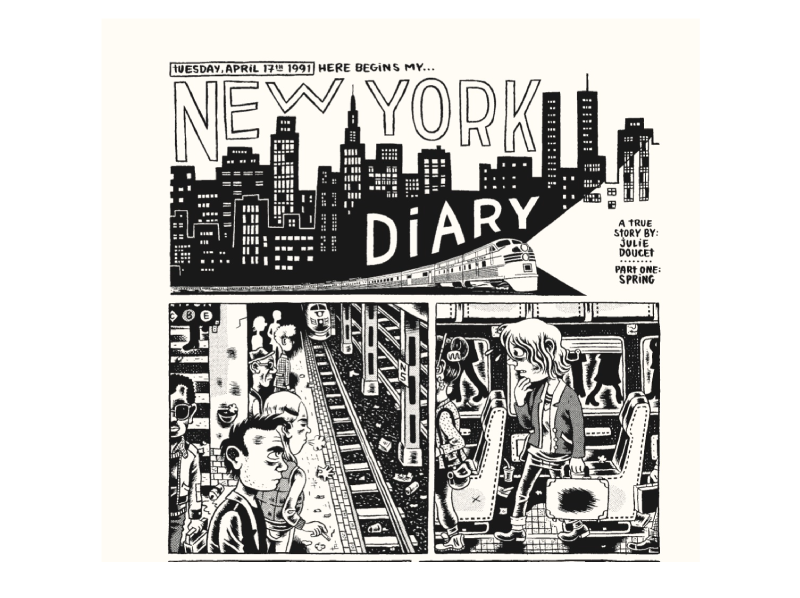

This is exemplified in what many regard as her best work, New York Diary, which also marks a shift away from the transgressive humor of her initial stories into more straightforward autobiography (even the title changes from “Dirty” to “Purty Plotte”). Here, she details a failed relationship with a man she moved in with after a brief love affair. Together they take drugs, have sex, and generally live a bohemian lifestyle in Washington Heights. But Doucet soon finds her lover to be needy and resentful of her budding success, and the relationship quickly deteriorates. As it comes to its inevitable conclusion, Doucet heads to a new city, Seattle, declaring to the reader that she has “no regrets.” A brass band plays as she makes her exit.

Doucet herself left comics not too long after, ending with the semi-autobiographical, semi-mystery tale The Madame Paul Affair. Since then, she’s focused instead on engravings, prints, and, most recently, collage.

While the world of indie and alternative comics was more welcoming to women than what passed for the mainstream in the 1990s, it was still a landscape largely dominated by men. The fact that Doucet was able to carve out such a unique place for herself is rather remarkable but the fact that she eventually looked around and decided it was time to leave, no regrets, isn’t. She was just too cool for the room. •

All images provided by the author.