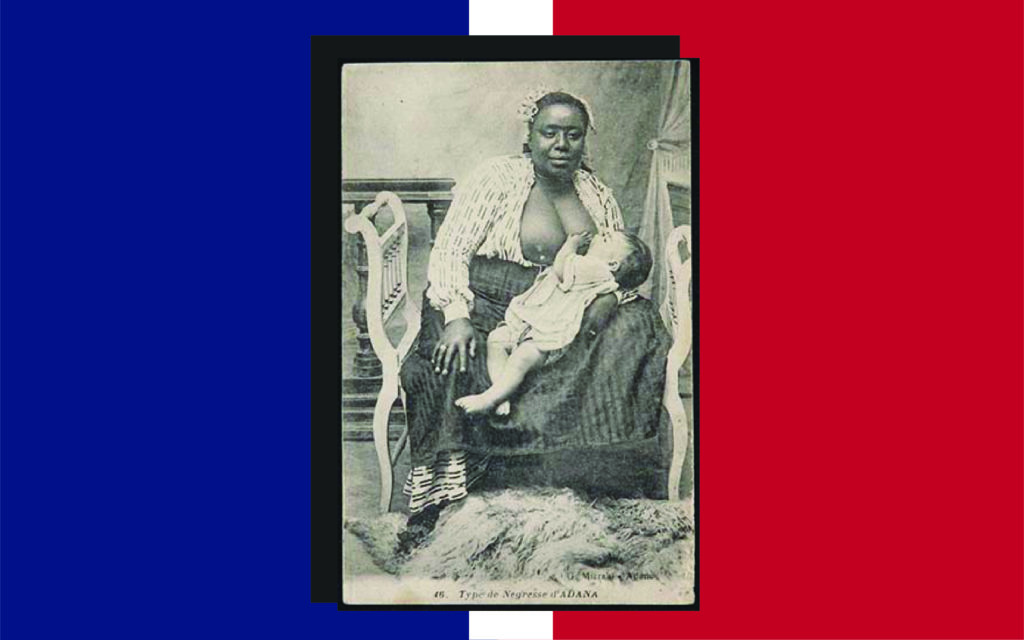

“There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism,” wrote Walter Benjamin in “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” “Just as such a document is not free of barbarism, barbarism taints also the manner in which it was transmitted from one owner to another.” We are presented with one such document in the opening moments of “Confederates,” a play by Dominique Morisseau that recently opened at the Pershing Square Signature Theater. Blown up on a slide is a sepia-toned picture of an enslaved African woman breastfeeding a white child. The context for the image is withheld until the very end, yet it is enough to feel, in our nerve endings, that we’re looking at a snapshot of oppression and exploitation. Our eyes have scarcely had a chance to take in the entire image when it’s replaced with a slightly different one. Sandra, a Black professor played by Michelle Wilson, recounts how she discovered the new image — which shows her head photoshopped onto the original — tacked onto her office door. She demands that the university investigate. The opening gambit is also a provocation, to borrow from Ariella Azoulay to “watch” rather than simply look at an image: to pick up on the traces of what is being done to an image as much as what the image is doing. But I’m haring ahead of myself . . .

“For me, theatre is supposed to be a liberation sport,” writes Morisseau in the program note for her play. She also notes in her script that “Confederates” is a stylistic departure from her earlier plays. All of them, including naturalistic dramas like Pipeline and the Detroit ‘67 cycle, look at the interlocking forces of economic and social oppression that mark the lives of everyone from Black schoolchildren to workers at a metal stamping factory. “Confederates,” directed by Stori Ayers, doesn’t altogether abandon Morisseau’s avowed penchant for “earnest social dramas,” but twines the social drama — in this case, set on a university campus — with the legacy of slavery. It’s a doubleheader, set in two distinct time periods with bits of dialogue in one hotwiring responses in the other. As some American universities like Harvard and Georgetown continue to grapple with their foundational ties to slavery, it’s a play that seems especially relevant now.

The motor of “Confederates” travels along two tracks: on one, slaves contemplate becoming Union spies and snatching freedom from the jaws of rapacious southern landowners; on the other, Black professors dramatize the effects of institutional racism as one of them tries to secure tenure — more blood sport than liberation sport. Most of the actors take on dual roles, encouraging the conflation of timelines in this intermission-less drama. Sandra’s counterpart in the mid-19th century is Sara, a slave played by the redoubtable Kristolyn Lloyd. No sooner has Sandra left the stage than we travel back in time. The pillars and lanterns that frame Rachel Hauck’s rustic set effectively convey both a college campus and a slave cabin. In said cabin, we meet Sara, who is dressing a wound on her brother Abner (Elijah Jones). He is a runaway-come-Union-soldier, and on his clandestine visits to see his sister, he admonishes her to “be safe” and not draw too much attention to herself. Sara is having none of his chivalry; she announces, for what must be the umpteenth time, that she would prefer to make herself “useful,” whether by fighting for the Union or working as a nurse. They share the quarrelsome, lived-in familiarity of siblings, their exasperation towards each other modulated by affection.

Ministrations done, Abner . . . gets reincarnated as a college student. He’s exchanged his white tunic for a jacket and a backpack, from which he retrieves a laptop. (Ari Fulton’s period costumes come on and off with enviable ease, and the actors change right before us.) Malik (that’s his new name) has come to see Sandra during her office hours about a paper. The topic? This being a comparative politics course, he’s chosen to write about “the modern-day plantation in the workforce and its parallel to slavery during the time of the Civil War.” It seems compelling enough for a paper topic, and the more I listened to a highly caffeinated Malik rehash his thesis, the more I began to question why Sandra would mark it as “un-thorough and incomplete.” He points out that both the Emancipation Proclamation and affirmative action “came with multiple side clauses and loopholes . . . slaves still weren’t freed even after the Proclamation, and so-called minorities weren’t employed equally after affirmative action.” Malik is understandably worried that his status as a scholarship student could be jeopardized by a subpar grade. Less subtly, Malik’s chosen topic also functions as a stalking horse for the play’s moral message. What ensues is an argument in which student and teacher talk at cross purposes: Sandra stands by her assessment that the essay lacks a rigorous, “airtight” argument, but Malik thinks Sandra harbors an “unconscious bias” against him. They only settle into a détente when Sandra admits that she thinks of him as “one of the brightest students” in class and reminds him that he can re-write the paper for a higher grade.

Back to the 1860s. Sara is praying by candlelight when she’s disturbed by a knock at the door. Hastily, she throws her contraband Bible in a bag of feathers before admitting the visitor. Her caller is Missy Sue, a white young woman played as a babbling flibbertigibbet by Kenzie Ross. There’s a bit too much exposition in this section, as Missy Sue recounts how she has returned from the North after her husband discovers she can’t bear children. With her husband gone, she’s decided to “pay a visit to my long lost friend” and proceeds to divulge her “ideas for social progression.” She claims to want to help Sara and Abner achieve freedom. To that end, she proposes setting Sara up as a house slave, allowing her to covertly jot down Confederacy plans as they are bruited about the house.

Before Sara has time to give her consent, Missy Sue is gone — and then back in a flash, this time as Candice, an oversharing assistant in tights and a short skirt. The power dynamic has ostensibly shifted: Candice confesses, a bit treacly, that “this job saved my life.” Instead of filling her time with meetings and clubs among the 19th century socially progressive set, she’s now tasked with organizing Sandra’s calendar. A huge color-coded posterboard is propped up on Sandra’s desk as Candice updates her on new requests for appointments. Occasionally, the dialogue stretches credulity: how many students, for instance, would broach the topic of a professor’s divorce in the insouciant manner Candice does? “We get it. We don’t hold it against you,” she says at one point, making excuses for Sandra’s ignored emails. And how many student assistants are empowered to access their professor’s emails to help “clean it up”? Such infelicities give away some of the play’s suspense, but ultimately the play is structured less as a “Whodunit” or procedural than as a trialogue: with its twin plots, with the image, and with the audience.

The hinge between the two storylines is the aforementioned photo that also bookends the performance. The image next comes to mind when we go back to the plantation, where LuAnne, a slave played with voluptuous verve by Andrea Patterson, rhapsodizes to Sara about her mother, “a steel rod woman” who held suckling babies to her breast all her life. LuAnne wistfully recalls how Mama Mabel fed “all them bastard chir’ren Master brought back for her to tend to” and additionally looked after other slave children. She cast a protective circle about her, her presence acting as a sheath for slavery’s sword: those within her care “never got whipped nor branded.” It’s a rare moment of connection, forged by memory, between two estranged childhood friends. And it disperses all too quickly, as they go back to fighting about freedom. For LuAnne, sleeping with the master, for all that it smacks of betrayal of her mother’s memory, at least gives her a sense of agency. Sara, who is “barren as the forest in the winter,” is more distrustful of both her master and mistress. Not for her their pyrite promises; she’d rather burn her bridges and seek out freedom on her own terms.

At the end of 100 minutes, an usher hands us a note, like a codicil to a confession, from projection designer Kate Freer that explains the source of the archival image. Called “Type de Negresse d’ADANA,” the photo wended its way through a circuit of white privilege, traveling from France into the hands of Leonard Lauder of New York, who bequeathed it to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. You can find it on the museum’s website and on any search engine (when I emailed the museum to find out more and confirm if it was currently on display, I received no reply). Freer further notes that the anonymous woman “had no say in the use of her image or the use of her body.” The play purports to “reclaim her narrative from [her] captors, from the dominant class of oppressors.” It’s a bold move. And “narrative” is what Morisseau provides: instead of stasis—a coerced image that’s left to stand as a synecdoche for systems of dispossession — she gives us movement and sound.

Some scholars — and I’m thinking here primarily of Tina M. Campt — would urge us to pick up on the “vibrations” or “sonic frequencies” of otherwise “recalcitrant” images. That seems relevant here. In her book Listening to Images, Campt discusses the ethics of looking at, or rather, viewing, “identification photography,” or photographs imbricated in colonial or classificatory projects, like passport pictures, portraits made by Christian missionaries, and convict photos. She asks: “How do we contend with images intended not to figure black subjects, but to delineate instead differential or degraded forms of personhood or subjection — images produced with the purpose of tracking, cataloging, and constraining the movement of blacks?” “Confederates” advances an indirect answer to this by granting us, albeit provisionally, a more holistic view of the photographed woman: at the end of the play, Sara reveals that the breastfeeding woman was her mother. Fulfilling an early wish of Missy Sue’s, Sara now appears before a presumably white, abolitionist audience “to tell you something ‘bout me and slavery to help you be a friend for emancipation” (emphasis mine). Here, the play animates different, subterranean registers of sound, and, like Campt, reminds us that we should not confuse a “quiet” image for a “silent” one. Sara’s barrenness, once considered a curse, has become her passport to freedom. She, unlike her mother, is not condemned to a life of nursing white children or bearing her own and watching them be sold into slavery. “Confederates” culminates in this defiant line: “Bondage begin and end with me.” There is no curtain call; instead, we are left with one final impression: of Sandra and Sara sharing the stage for the first and last time, staring at each other across an expanse of time that is really no time at all. •