On the surface, it looks a lot like your typical Sunday School. There are children gathered at the feet of the woman teaching the class. They are singing Christmas carols, listening to stories about how we as people came to be on this earth, making arts and crafts. It could be taking place in any church basement across America.

Until you start to listen to the words of this particular version of “Silent Night.”

Silent night, holy night

all is calm, all is bright

planets gracefully circle the Sun

Stardust cycles through everyone

Life abounds upon Earth

Life abounds upon Earth

They begin another song, this one without the familiar melody.

In the beginning

was the Great Radiance

14 billion years ago

out of the fireball

came simple hydrogen

and helium from that great glow

The children gather now to make what look like rosaries, and the instructor spreads out a large selection of beads. Only, rather than using them to count prayers, the beads are there to help the children contemplate the stages of life development. The first bead represents the Big Bang, next the formation of the stars, then the birth of the planets, the beginning of life on Earth, and so on.

“You are all made of Stardust,” the instructor tells the children. At this point, the instructor might anoint the children’s foreheads with glitter in a ritual called Cosmic Communion, mimicking the rite of holy baptism. The children are asked to sing again,

We are made of stardust

every single atom

of carbon and of oxygen, calcium, and iron

The songs, stories, and crafts were developed into a curriculum by former science writer and editor Connie Barlow, as part of a movement some call Evolutionary Spirituality, some Secular Spirituality, and others Religious Naturalism. For the last 15 years, Barlow and her husband Michael Dowd have been traveling around the country, lecturing, giving sermons, and teaching their children programs to youth leaders and the kids themselves. They average 150 speaking engagements a year at community centers, Unitarian Universalist churches, schools, and retreats. They, and other evolutionary spiritualists like them, are here to spread the good news — only here the good news is that God does not exist. Allegorical creation stories are replaced with stories about the Big Bang, God is replaced by science, and awe is reserved for the power of nature, not the Almighty.

The rise of evolutionary spirituality comes at a tricky time for atheism. In the past decade, atheism has gained some prominence in American culture after a long time of society seeing a lack of religious belief as a sign of deviance or hubris. Only three percent of Americans identify as atheists and an additional four percent identify as agnostics, but a full 30 percent of the population now considers themselves to be secular, or religiously unaffiliated. Books like Christopher Hitchens’s God Is Not Great and Richard Dawkins’s The God Delusion were bestsellers, and atheist thinking has entered the intellectual discourse. But with the rise of visibility comes the increased awareness of atheism’s limitations. From charges of atheism being its own form of dogmatic belief, to accusations of atheists simply worshiping science, to real problems with Islamophobia and racism within the community and its leaders, atheism will have to confront these issues if it wants to continue to grow.

But perhaps the issue most difficult to solve with atheism is that it is, by definition, against something, not for something. It is a tool for dismantling, not building. Atheism, so far, has been about destroying the (in their words) illusion that there is a creator, an afterlife, and a spiritual purpose to life on earth. They believe divinity is a human creation, an emotional crutch, to avoid having to deal with the meaninglessness of life. The rise of atheism coincided with a rise in Western secularism, but also with the growing distrust of organized religion, following religious scandals like sexual abuse in the Catholic church, terrorism committed with religious justifications, and con artists working as televangelists in the Protestant faith. These scandals created a real crisis in faith, and atheism gained legitimacy alongside them.

But if atheism is simply an opposition to religious culture, then how does — or should — it create its own culture? Religious culture grows out of a shared belief in something, a god or a set of values or an idea — so can a shared disbelief provide the same kind of community? If atheism and secularism have created a void, the question in front of these groups is: What does one do with that void? Does one live alongside it, as rationalists like Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, and other materialists believe? Or can one — should one — create a kind of godless religion, something that fills the emotional and spiritual needs that religion did, without the underlying belief in divinity? As traditional religions continue to lose followers and more people drift toward non-belief, that question will have ramifications for the larger Western culture, even as it creates controversy within the smaller atheist community.

I take the bus from Portland into Hood River, Oregon, to see Connie Barlow and Michael Dowd in person after a deep dive in their YouTube account. Hood River is a kind of recreational center for the white upper middle class, with water kite skiing, rock climbing, and kayaking along the river, the riverside full of RVs. As I walk to find coffee at six a.m., it’s breathtakingly beautiful, with the moon hanging over the mountains and dawn turning the sky all rosy. The downtown area has a cold-pressed juice cafe, a pot dispensary, several outdoor recreational supply shops, but no simple grocery store.

On Sunday morning, Barlow and Dowd are speaking at the Riverside Community Church, although Barlow has a cold, so Dowd will be handling the service. It’s one of these vague, non-denominational churches that seems more about fostering community and advocating service than teaching any one specific set of beliefs. There are about 50 people in attendance, and all but two of them are white. A child runs down the aisle, and a mother yells at him sharply, “Faulkner!” The parking lot is full of SUVs and minivans.

The service opens with a kind of faux-Native American benediction, calling on the four directions to be present at this meeting. The scripture reading is a poem by Shel Silverstein and prayer time is called meditation. When the children are gathered at the front of the church for storytime, Dowd, wearing a bright green clergy shirt and collar, explains to them the meaning of the secular rosary he has with him and he tells them they’ll be making their own beads while the adults listen to the sermon.

It’s an almost exact copy of the Methodist services I attended as a child in rural Kansas, minus the angry Protestant God, and with the added bonus of the children getting to leave during the sermon. Children were required to listen to the full service in my church and somehow expected not to kick their sister that whole, boring time. Not for the first time since reading about the evolutionary spiritualists does it surprise me that anyone would choose to continue coming to services like these without the religious obligation.

The sermon is called “Can Religion Be Saved in Time to Save Humanity?” As Dowd and Barlow explained in a video on their YouTube page, in late 2012 they had a “come-to-Jesus moment” with climate change, and converting others to the climate change cause has been their mission ever since. In their many videos, Dowd sometimes refers to himself as Reverend Reality, as he believes God can simply be replaced by the idea of “reality,” that nature is the new testament, and that climate change is calling on us to convert. Since that revelation, the focus of their sermons and writings have been on using religious feeling to inspire people to take action on climate change.

“God isn’t in heaven,” Dowd preaches, and the idea of a remote God has led to a disastrous relationship between man and nature. By not seeing the creation itself as divine, we have felt free to plunder resources and destroy ecosystems. But, he says, “God can be realized through a green lens.” We can shift our thinking so that God is the earth, He is nature, and by honoring nature we are honoring reality. “Our brains inherently give human characteristics” to things we don’t understand, Dowd tells us. In order to grasp the power of nature, to give meaning to our existence, we created the idea of God. We don’t need an afterlife, we can create heaven on earth. The carelessness with which humans have treated the earth is the new sin, a form of “intergenerational evil.” He asks us instead to be saviors, to be redeemers of the planet.

Dowd seems careful not to say flatly that there is no God, but he repeatedly substitutes the word reality for God as he moves through his sermon. He is a dynamic speaker. If one simply turned down the volume for a minute it would be easy to assume this was a traditional religious revival, from his clergy shirt to the way he stalks the stage and works himself up. Dowd is in his late 50s, but there’s a lot of fire still there. The audience nods, heads bowed, feeling the energy. It would not be surprising if someone walked out with a box of snakes, or jumped up with hands raised, shouting “hallelujah!” But this is the Pacific Northwest, and the pews are comfortable, so everyone keeps their seat.

I sneak out a little early as people keep trying to come up and talk to me and shake my hand, but also I want to digest the sermon a little before I meet Dowd and Barlow for an interview later that afternoon. The logic of the sermon seems mixed: In the way that in Christopher Hitchens’s God is Not Great, he implied that because there have been so many wars waged with religious justifications that surely if we just removed religion, the wars would end and there would be peace. Hitchens rather immediately disproved this theory through his secular support for the invasion of Iraq. In terms of Dowd’s sermon, surely it’s capitalists, not religious fundamentalists who are running the oil companies. And surely it’s human nature, and not religion, that causes the world’s ills. Remove the religion, and we’ll still be left with the greed, the bloodlust, the fear, and the myopia that has created the world we live in.

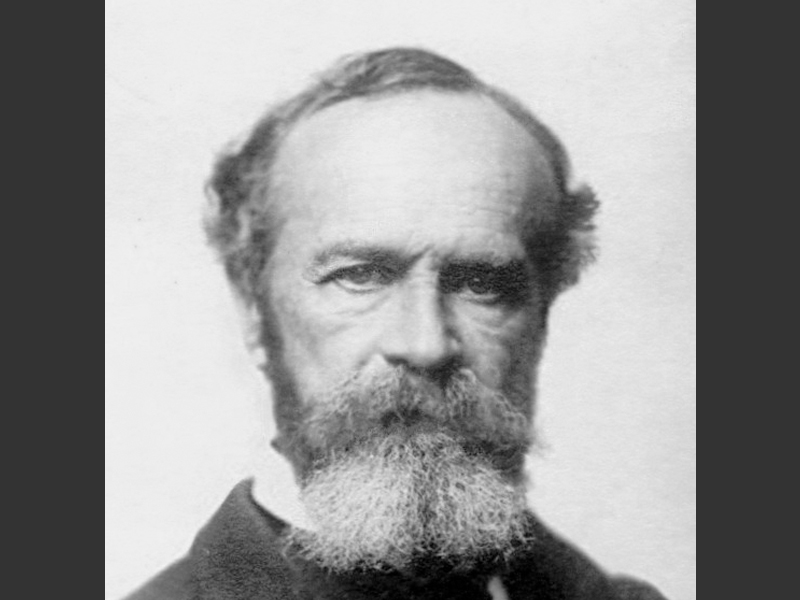

The closing remarks of the service were by Carl Sagan: “Science is at least in part informed worship.” The evolutionary spirituality approach seems to be half Carl Sagan and half William James. The American philosopher and psychologist James spoke as part of the prestigious Gifford Lectures series in 1901 and 1902, on the subject of “natural theology.” Collected as The Varieties of Religious Experience, the lectures outline what the psychological experience of religious belief is, when the actual divine elements are subtracted. What prayer feels like, what it does for the petitioner, what mystical experiences feel like, and how they affect the person having them. What he did, then, at least on a surface level, was empty religion of God and give a template for what a full religion, if one wanted to construct a new religion from the ground up, would require.

James’s own religious beliefs were complicated. The son of a Swedenborgian philosopher, he was attracted to mysticism and paranormal phenomena — he for a time acted as president of the Society for Psychical Research — but wrote of his inability to give himself over to the religious experience and make the leap into full belief. But he was empathetic to those who could and did, and he was very skeptical of those who were certain no god existed. (“He believes in No-God, and he worships him,” he jokes about an atheist student of his.)

That Jamesian empathy is missing from much of the evolutionary spirituality writing that references his work. In his forthcoming in 2017 book Inventing God: Psychology of Belief and the Rise of Secular Spirituality, philosopher and psychologist Jon Mills references James more than a dozen times, but rather than sharing his understanding for the believer, Mills shows only pity for her. For Mills, the idea of God is “a global defense that gives billions of people a sense of purpose and meaning and allows them to function in the face of existential absurdity,” and, he continues,

most of the world population are either illiterate or uneducated, they are not intellectually capable or enlightened enough to live life on its own terms free of this type of psychological need for self-protection from the truth of reality.

That’s in comparison to atheists, whom he calls humanists, “who are educated, well-informed, and disposed to think critically about the God question.“

Mills uses James to deconstruct the idea that spirituality needs a god at all — because, as he puts it, God is an impossibility, “actually a semiotic invention and symbolization of ideal value.” It’s a more academic way of saying what Dowd mentioned in his sermon, that gods are merely personifications of abstract concepts or feelings. Mills admits that religion does have its attractive qualities, such as its method for distributing ethical guidelines and giving form to a feeling of the sublime, and that those qualities are worth preserving even if the idea of divinity or anything beyond the material realm should be discarded as being illogical.

“What does it mean to have spirituality without God?” he asks. “At the very least, it must necessarily involve adopting the ethical way of being.” Spirituality then for Mills takes what was once a conversation or interaction between individual and God and turns it into a conversation within oneself. It’s about negotiating the relationship to the Other (society, or the earth, or a lover) by doing good and cultivating empathy. And this humanist take on ethics is superior to religious ethics because “we don’t need to appeal to celestial authority or fear to promote their value or to motivate good actions.”

It’s a common misunderstanding of religion, that one acts in a certain way because they are afraid of punishment in the afterlife, that religion is not in itself capable and effective at building empathy through the same feelings an atheist might have. What Mills left out is how one might be able to nurture compassion, empathy, and know what is the “right thing to do” merely through internal feelings. Determining your own code of ethics and what is right and wrong seems as vulnerable to self-serving mistake as determining your own interpretation of God’s will by reading the Quran or Bible.

Other writers in this tradition, like Thomas Berry and William Catton, Jr., prefer a Carl Sagan approach to religion, anchoring the spiritual feelings in the cosmos rather than in the supernatural realm. Berry, an “eco-theologian” and scholar, called for a new creation story, one that can supersede allegorical creation stories, and Dowd credits Berry as a major influence in the creation of what he calls “The Great Story.” Dowd’s “The Great Story” is the scientific explanation of how the universe came to be, but written with an allegorical tone, in the hopes that the Big Bang can somehow contain the same deeper meaning as the Garden of Eden or other creation myths.

That search for meaning within science inspired Sagan’s own appearance at the Gifford Lectures, which were collected as The Varieties of Scientific Experience. In those lectures, Sagan criticizes religion through a scientific lens, asking that if the holy books were actually divinely inspired, why God did not pass down information that would prove his existence scientifically. Or, he could have carved his own name onto the planet in some way. He wrote, “God could have engraved the Ten Commandments on the Moon. Large. Ten kilometers across per commandment.” (No one takes the Bible more literally than an atheist.) As it is, though, there is no proof that God exists, so using a scientific world-view makes more sense than a religious one. Those religious feelings like awe, the sublime, inner-peace and meaning could be met through the scientific exploration of our world. An oft-quoted line from Sagan’s Varieties is, “The best way I know to engage the religious sensibility, the sense of awe, is to look up on a clear night.”

But as philosopher and longtime critic of materialism John Gray writes in his latest book, The Soul of the Marionette, “Science is a method of inquiry, not a view of the world.” Science can tell us the facts, but when it comes down to giving our lives meaning, to tell us how we should live, “these are questions for philosophy or religion, not science.”

Philosopher Mary Midgley, in books like Evolution as Religion, echoes Gray’s concerns, saying religion should not attempt to be science (as when Creationists use a literal interpretation of the Bible to explain how the universe was created and life on the planet developed), nor should science attempt to be religion (as with the evolutionary spiritualists using scientific information as allegory). Each sphere performs a specific function and mixing the two can lead to distortions of both. When science becomes the basis for a belief system, one is less likely to question it. Science is at as great a risk for turning into dogma as religion, if it is misused.

When I asked Barlow “What comes before your mind corresponding to the words God, Heaven, Angels, etc?”, she snarled and responded, “Supernatural bullshit.”

When we first spoke, she had mentioned William James, and so I thought I would ask her a questionnaire included in Varieties of Religious Experience that a nonbeliever had answered, but she did not seemed amused by the task. The short list of questions, like “What does Religion mean to you?” and “What things work most strongly on your emotions?” visibly grated on her.

She became more comfortable when the subject turned back to evolution. Her books on evolutionary theory were published by MIT Press, and she was respected in her field. She gets up at one point during the interview to demonstrate to me how sloths use their four appendages to grip the tree trunk to climb up and down and how their limbs evolved to best let that happen.

She tells me about how a scientific worldview can help a child deal with the reality of death, by telling them that when their grandmother dies, she “becomes an ancestor.” And that before they were born, “they were stardust.”

But why, I ask her, is a church the proper setting to have this conversation with children, rather than school? It was Richard Dawkins, she tells me, “who forced me to get real about liberal religious tolerance.” We were sitting in the park, as it was a beautiful clear day, and at that moment a child almost crash-landed a kite into my skull. Losing my place in the conversation, I change the subject, but when I come across her response in my notes later, I email to ask her to clarify:

I realized that any child should not be labeled as being adjectivally any religion. Adults, yes. But a child is (a) given no choice and (b) has no capability for discernment . . . As I recall [Dawkins] says, we would all agree that nobody would think it right to call a child a Republican child or a communist child or a capitalist child. Yet we somehow forget that when we liberals have unthinkingly called kids a Catholic child, a Jewish child, or a Muslim child. No, they are children being raised by a Catholic family that tends to vote Democratic in a capitalist society. Period.

In one of the YouTube videos showing Barlow instructing others on how to use her curricula, she talks about the importance of “indoctrinating” children, of imprinting their minds with a scientifically sound creation story. This will then integrate with what they learn at school, which will save them from having to question their belief system.

“I felt like we were doing nothing to give kids a big picture of our own, and my view of children is there’s a certain age, starting maybe 10, 12 to 14, when they start to question everything. But until then, you’ve got to give them a story and they just take it in. You give them a big picture so they understand who they are,” she tells me.

According to Dowd, it was luck and good timing that set him and Barlow on the road 15 years ago. They gave up their home and started touring the country in their van. Often they would stay with their followers, moving from place to place every few days. Now, Dowd says, they have a stable enough following that they can stay in people’s second houses and vacation homes, rather than taking up space in someone’s spare bedroom.

But the timing — late 2001, early 2002 — reminded me of something Carl Sagan’s widow and collaborator Ann Druyan, told the New York Times back in 2008 about her and her late husband’s relationship with the men who have become the most prominent spokespeople for atheism and secular culture. After 9/11, many scientists felt like the “truce” between science and religion was off, that religion had failed, and the extreme violence of the fundamentalists was proof of this, and so science could, basically, invade religion’s space. “A lot of scientists were mad as hell, and they weren’t going to take it anymore,” she said.

In one of her videos, Barlow spoke of how her program could inoculate a young seeker facing a crisis of faith from falling into the trap of fundamentalism, because science would ground them. “Without a meaningful, believable story for us to believe in, people have no idea how to think about the big picture.” And without a big picture, the young are “vulnerable to searching.” Religion can no longer provide a satisfactory big-picture story, because science, she suggests, has disproved it. But, she warns, there is a “limited window to indoctrinate children,” and if they are not indoctrinated by the right people, “they may get it from classmates” of more traditional religions.

Dowd had his own brush with fundamentalism. Despite being raised Catholic, and not a particularly devoted version of Catholicism, after falling into some trouble with substance abuse as a teenager, he experienced a revelation, a vision during his military service in Germany when he was, he said, either 21 or 22. He found himself drawn to an evangelical church, and later enrolled in the Evangel University in Springfield, Missouri.

“I was a young-earth creationist,” he tells me, taking on fully the apocalyptic worldview of the Evangelicals at the time. He worked as a street minister during this time, believing fully that the world was in the end times and that those who did not find their way to Jesus would suffer eternal damnation. He was more of a hardliner than some of the college staff. When he found a textbook at the college that legitimized the theory of evolution, he took a stand against it and publicly declared that “Satan has a hand in this college.”

His belief seemed so sustained by the young-earth theory that the idea held by many evangelicals that evolution is a lie and all life in the universe and on earth was created less than 10,000 years ago, that it was through scientific education that Dowd lost his faith. Once he learned of the evidence that supported the theory of evolution, despite the fact that Christian leaders since the very early years of the religion have cautioned that the creation story should be understood symbolically and not literally, the evangelical church lost its hold on him.

But speaking to him now, it’s not hard to see the apocalypse still lighting up his eyes. His newly found focus on climate change has renewed his sense of purpose. A cataclysm from climate change is coming, he tells me. It’s irreversible. “We will go into another Dark Age.” But after that, after the suffering, perhaps it will bring in a new day, a new way of life. A simpler way of life. He criticizes techno-optimists who believe we can invent our way out of this tragedy, because, he says, after the energy crisis we will have nothing to run the technology on. We’ll have to return to living in smaller communities, there will be less isolation because we will need each other to survive, and we will live more in-tune with nature.

It is almost like Dowd has a fundamental need to believe that this world, as violent and sinful and flawed as it is, will end and something more pure and balanced will take its place. When one religious belief that answered that need was proven to be imperfect, he simply replaced it with a variant. His need remained the same, even as the religious structure — either a climate change apocalypse or Jesus’s return to the earth — he relied upon changed.

Midgley warned that evolution had become a new “secular religion,” “put forward as [a] substitute for religion, able to replace it in public acceptance.” She continues, in Evolution as a Religion, that evolution has “like the great religions . . . large-scale, ambitious systems of thought, designed to articulate, defend, and justify their ideas — in short, ideologies.”

In late 2012, the highly respected philosopher Thomas Nagel, author of the classic essay “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?”, released Mind and Cosmos: Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature is Almost Certainly False. Since the rise of atheist thought, a materialist worldview had taken the group over, led by thinkers like Richard Dawkins and Daniel Dennett. They argued that the universe is made solely of matter, that the existence of life is merely an accident, and that the development of the world can be understood through Darwinian theories of evolution. As geneticist Francis Crick phrased it, “‘You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules. Who you are is nothing but a pack of neurons.” Nagel, who repeatedly reminds the reader in Mind and Cosmos that he does not believe in divinity, argued against this version of the world, saying that consciousness and mind are essential components of life in the universe and could not have developed in the way we currently understand life to have developed: that is, randomly. We have not, and cannot using materialist, Darwinian conceptions of life, understand how life developed from non-life, and how mind arose from matter. He wrote, “It is prima facie highly implausible that life as we know it is the result of a sequence of physical accidents together with the mechanism of natural selection.” Rather than theorizing that some sort of Creator meddled with the development of life, as intelligent design theorists posit, Nagel simply believes our understanding of the universe is limited, and that some reality, a larger form of consciousness we cannot yet grasp lies underneath our current conceptions.

It was presented as a theory, but it was responded to with ideology. Reviews of the book and responses by thinkers like Steven Pinker were overwhelmingly negative, and Nagel was talked about as if he had lost his mind. Pinker’s “What has gotten into Thomas Nagel?” is a representative response. Rather than engaging with his ideas, he was attacked as a person. Suddenly, the most (arguably) famous and respected philosopher in America was treated as if he were a crazy person mumbling on the street corner. Reviews that meant to dismantle Nagel’s argument that the materialist New-Darwinist conception of nature couldn’t be true contained sentences like, “the materialist Neo-Darwinist conception of nature is almost certainly true.” The Weekly Standard covered the controversy with the headline “The Heretic,” and illustrated it with an image of Nagel burning at the stake. Philosophers’ Magazine went so far as to call Oxford University Press “irresponsible” for publishing the book, suggesting it will merely embolden creationists and intelligent design theorists.

Scientists have allowed their scientific theories to become ideology, imbuing them with a meaning beyond simple fact. And so when that ideology was attacked, they responded in the same way a fundamentalist Christian would if an evolutionist questioned the young-earth theory. In short: “You are wrong, I am right.” Whatever you rely on to give your life meaning becomes sacred to you, even if it is a scientific theory. And the people who espouse those views, like Dawkins, Pinker, or Dennett, become untouchable religious figures.

I reached out to Nagel, to see if he would like to comment on the reaction to his book, but he politely declined, saying he has a policy never to do interviews. His editor at Oxford University Press, Peter Ohlin, simply stated that Mind and Cosmos “challenges so many deeply-held assumptions about the world and our place in it . . . it’s understandable that it would ruffle feathers.”

There seems to be something about human nature that tends toward fundamentalism, that it is not merely a byproduct of religion. If that is something secularists and scientists wish to rid the world of, going at it by ridding the world of religion will merely change its flavor.

“Because it is directed to all of humanity,” John Gray writes in The Soul of the Marionette, “the Christian religion is usually praised, even by its critics, as an advance on Judaism.” But Gray disagrees universality is a virtue. “Modern rationalism renews the central error of Christianity — the claim to have revealed the good life for all of humankind . . . What Leopardi called ‘the barbarism of reason’ — the project of remaking the world on a more rational model — was the militant evangelism of Christianity in a more dangerous form.”

As I was leaving Hood River, it seemed clear just how much evolutionary spirituality was based in Christianity, even as it claimed to be against it. From the rituals and structure of the church services to its claims of universality to its work at conversion, it was just a slightly reworked Protestantism.

The irrational sides of ourselves have long been a problem for humans. There are those who try to give it expression through religion, those who try to control it or deny it through rationalism, those who splash around in it through psychoanalysis. And while this new group of atheists may think they can prevent the irrational’s excesses, I think soon they’ll find they are in the same boat as everyone else. Flawed, irrational, and human. •

Feature image by 星耀晨曦. Images courtesy of Materialscientist via Wikimedia Commons and Sam Beebe and Clay Alchemist via Flickr (Creative Commons). Other images courtesy of Shannon Sands.