Once we were mighty. Once we were legion. Once we reigned over colleges and universities like demigods. Well, OK, we English majors were never that important, except maybe in our own eyes. According to a report in the New York Times, degrees awarded in English at American universities fell from seven point six percent of the total in 1971 to three point one percent of the total in 2011 — which goes to show, I suppose, that the golden age was never quite so golden. Still, better the periphery than where we are now — the periphery of the periphery.

One of the less-happy consequences of my decision to major in English 40 years ago is that I haven’t met many (or any) people who share my enthusiasm for the writings of John Dryden. Another is that I make about as much money as a janitor and live in one of the most expensive cities in the world. I knew what I signed up for. My life sentence as an English major has taught me not to care overly much about what are laughingly called “the good things in life.” For better or worse, I can’t look at the glossy advertisements in The New Yorker without a feeling of cognitive dissonance. How could anyone who reads the poems and short stories and criticism in that magazine really want all that crap? If that’s a prejudice, the fault lies in me, not in my discipline, which includes plenty of practitioners with a somewhat more realistic financial outlook than my own. Anyway, for me, it’s less a discipline than a passion. I expect that that beleaguered three point one percent on campuses today feel much the same way. Against the advice of their parents, the social pressure of their peers, and the severely utilitarian direction of American society, they obdurately go on piling up their useless, unremunerative literary courses. See the trouble you get into when you listen to your soul?

Traditionally, writing and teaching at the university level have been the career paths of choice for English majors. Nice work if you can get it. I never could, which is why I’ve spent most of my life as a librarian. My up and down career as a writer, on the other hand, has afforded me much satisfaction and very little money. In fact, except for a few years when I worked as a staff writer for a small and specialized publishing house, it has never been a “career” at all. Because it’s not my principal livelihood, I can write what I want, when I want for a small but select readership that, from what I can tell, generally appreciates my efforts and sometimes (just to keep things interesting) rips me to shreds. My real career as a librarian is all very well, but since it’s fundamentally a paycheck, I can’t muster excessive enthusiasm for an institution that provides a lifelong education free of charge for the broadest conceivable public and generally represents American values at their best. I didn’t major in English to serve American values. I majored in English so that I could spend the rest of my life arguing about books and culture, even if I had to do so in my off hours, even if the argument was chiefly with myself. I still think it was the best decision I ever made.

So what do today’s redoubtable, courageous, and zealous English majors have to look forward to — a life as exiguous or compromised as my own? They should be so lucky. Their prospects are considerably bleaker and their college debts considerably steeper. The fortunate few will get tenure-track positions or the rare editorial job that may allow them to pay off their debts in less than a lifetime. The rest will find alternatives (note to panicky English majors contemplating life after graduation: anyone can be a librarian) or work as indentured servants in the academy, perhaps moonlighting as waitresses or tutors. I hope they’ll be able to tell themselves what I’ve never doubted: It was worth it.

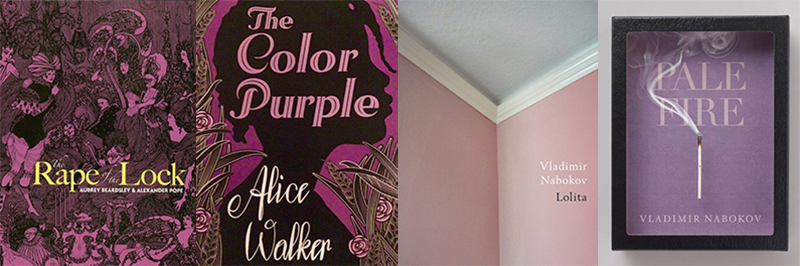

Perhaps my sense of solidarity with my younger comrades is misplaced. First of all, given their ever-decreasing numbers, I rarely meet English majors anymore, and when I do we often end up talking past each other. That’s partly because we haven’t read the same books. I can’t believe they haven’t read The Rape of the Lock. They can’t believe I haven’t read The Color Purple. They’re right about one thing, though: Far from representing eternal verities, the canon necessarily “encodes” reigning social prejudices, so that today’s fixation on race, gender, and class will one day look as narrow as yesterday’s fixation on irony, paradox, and ambiguity. Actually, it looks narrow already, but I’m an irony and paradox guy, so anything I have to say on the subject of canon formation has to be understood as the discourse of white male hegemony contested by discursive modes subversive of the heteropatriarchal project. Or something like that. The thing that doesn’t change is what Wordsworth called “the grand elementary principle of pleasure.” This is where the professoriate, I believe, has made things difficult for itself. Given the relentless technological and entrepreneurial drive of our society, English majors probably would have been knocked off their perch anyway. But perhaps literary study might have a little more clout and might attract a few more students if it weren’t as if often is these days, so puritanical, so judgmental, so entirely persuaded that the personal is, always and everywhere, the political. I once had a dear friend who was a tenured “Americanist.” We could talk about everything but literature. Once, however, in an outburst of idealism (there was nothing in the least cynical or careerist about Hannah), she favored me with something like a credo: “If you can’t use literature to interrogate social and political realities that still condition us, then it’s just a shallow and narcissistic aestheticism.” I wanted to raise my hand as if from the back of her classroom and shout, “Me! Me! Me! I’m a shallow and narcissistic aesthete! My impeccably progressive politics will never extenuate the crimes of my race and gender, but we must agree to disagree: Political and literary values are not identical.”

Against Hannah and so many of her colleagues, I read for what Vladimir Nabokov called “aesthetic bliss.” Nabokov himself is a good example of how challenging that bliss can be. His two greatest novels depict a pedophile using every resource available to him as a hyper-educated white male to sexually exploit an orphaned, working class, 12-year-old girl and an outrageously libidinous gay foreigner brazenly asserting his sexuality in a provincial American college town not especially receptive to displays of “otherness . . .” How much more problematic can you get? Yet those novels are, among other things, verbal inventions at a self-conscious remove from the social realities that they critique; which is to say, they’re works of art. I couldn’t come close to encapsulating the ethical and epistemological complexities of Nabokov’s fiction, and I won’t try. But I will say this: His work affords me enormous pleasure. Nabokov’s wit, stylistic exuberance, and formal mastery are proverbial, but if anyone can read Lolita and Pale Fire without being disturbed as well as delighted (or being only disturbed and not delighted), that reader has learned nothing from the challenges to unthinking that Nabokov poses. That reader, I’ll venture to say, was never an English major.

I once read a review of a Paul Simon album in which the reviewer censured Simon for writing “English major lyrics.” Actually, I think Paul Simon writes very good lyrics, but yeah, he is an English major. (Queens College, class of 1963. Which suggests an alternative career path for English majors: rock stardom! What would the Eagles have been if Don Henley had majored in marketing?) Like Simon, we English majors (of any age) share a sensitivity to language that heightens awareness — of ourselves, of others, of the uses and abuses that language can be put to in the service of benign or malign ideologies. And here the usual defenses of literary study apply — that it broadens perspectives, encourages empathy, vanquishes complacency, and so on. They’re all true, in my opinion. Although you can still be a shit and read (or write) great literature, you’d probably be an even worse shit without it. David N. DeVries, in an essay in Inside Higher Education, nicely described why, at this moment, there has to be more than high-tech and financial advocacy emanating from our universities: “Without the patience instilled by immersing oneself in the mind-stretching range of the liberal arts, we are reduced to jittering appendages to the plastic devices in our hands, dried leaves scattering to the whims of market and fashion, addicts to money and status and consumption.” There are other ways to get to the same place, a place where personal autonomy can stand against market forces that impugn it and not everyone needs to go to college or read Nietzsche to get there. For me, however, studying literature in college, graduate school, and beyond (mostly beyond) has been a principle means by which I’ve resisted some of the worst ugliness out there and held on to what I hope are the better parts of myself. I do think that English professors would do well to embrace humanism and its scandalous, deviant offspring, pleasure, but I’m not in the academy and that’s not my battle to fight. Anyway, it’s not the rebarbative prose of cultural studies ideologues that has driven away potential English majors to the more congenial and profitable fields of management and computer science; it’s the market. Since the market is unlikely to change its mind anytime soon, English majors past and present might discover certain advantages in their comparative marginalization. Leave the blaze of noon to the engineering students. The twilight offers a no less ample field of vision and fewer temptations to an illusory certainty. •

Images courtesy of SamJJordan, AnveshPandra, José Carlos Cortizo Pérez, and Abee5 via Flickr (Creative Commons)