I found my soft, shiny stuffed dog on a tree of puppets at a souvenir shop in Big Sur. He was the color of asphalt with glossy plastic eyes that disappeared under his dark fur and floppy ears, making him look more like a bunny than a black Lab. His rear-end was plump and his tail thick. Through an opening in his chest, you could slip your hand inside. The feeling was intimate, like reaching into a shirt when one of the buttons has been undone.

The first time I did this, he came alive, opening his mouth to show off his pink tongue. I asked if he wanted to come home with me, and he nodded, his tail wagging from the flicker of my fingers. When I scratched behind his ears, he lifted his head as if he were relishing in the feeling.

“What should we call him?” I asked my husband.

“Blackie,” he said.

I thought it was a terrible name. But as we drove away, my dog puppet sticking his head out the window to enjoy the salty air and sweeping seaside views, I found I needed some way to refer to him, so the name stuck.

While visiting my parents in California, Blackie seemed nothing more than a silly indulgence. But once we got back to New York, I found myself spending more time with him than I would have a beloved stuffed animal from childhood. Pretending to feed him dog food. Making him lick and bite his front paws. Forcing him to chase his tail. I found it relaxing and enjoyable. Others found it a bit strange.

Although studies have shown that up to 40 percent of adults still sleep with stuffed animals, whether it’s normal for a 35-year-old woman to play with one daily does not seem to be part of mainstream scientific inquiry. Add the puppetry element into the mix (absent, of course, an audience), and people are bound to get a little weirded out.

One friend asked what it was exactly that I did with Blackie.

“He delivers messages around the house,” I said, “like, what’s for dinner?!”

To be fair, there are only two people around the house, my husband and me, and our house is really just a 500-square-foot apartment.

“He also likes to sing and dance,” I added, hoping it would make my predilection more palatable.

“Uh-huh,” she said, still skeptical.

As a child, I had a pile of stuffed creatures: elephants, bears, dogs, and aquatic mammals. I used the whole herd as a body pillow as I lay in bed reading books — my own private safari escape. It had always been my dream for them to one day come alive and gain the ability to speak. When I offered this as an explanation for my new stuffed animal puppet acquisition to my father, he summarily dismissed me, suggesting that even if they had come alive, they probably wouldn’t have had anything interesting to say.

“Sarah,” he said, in the imaginary baritone of a teddy bear. “Turn off the light.”

Once, when my sister was visiting, I sat on my gray leather sofa anxiously petting Blackie, using him as a sort of therapy dog.

“He’s nervous,” I told her, before putting the hand not inside of him up to my mouth and whispering toward her ear. “That means I’m nervous.”

“Yeah, I got it,” she said.

I found the act of petting Blackie to be soothing in two senses: I was both the one offering comfort and the one receiving it (me being also inside of the puppet). Does the act of nurturing not also nurture the nurturer? When I tried to explain the profundity of this dynamic to my husband, he said I was completely overthinking it.

“You just like to be constantly entertained,” he said, “so you don’t have to be alone with your thoughts.” Having very few friends, I had always thought aloneness was the problem of extroverts. I believed, with an air of judgment, those who kept their social schedules packed, did so to avoid being alone. Introverts, I now see, have the same problem; we just have greater incentive to adapt — and more time to develop our coping skills.

•

When I got Blackie, I had a husband I loved, a job I liked, and no plans for children. But I still felt something was missing from my life. I decided to make a vision board, a collage of images representing various areas of my life (love, intellectual fulfillment, health, etc.). I thought if I stared at it long enough, a solution to my problem would present itself — my problem being nothing more than an indefinable sense of longing.

On the board, I’d cut out and pasted an image of an older woman, a wildlife conservationist, tenderly putting her hand to the cheek of a baby elephant orphan. When I carefully applied the printout using a glue stick, I meant it to symbolize alternative motherhood. But while staring at the photo, I began to think that I identified more with the alternative child. There was something familiar about the little elephant’s position. Have we not all felt alone in the world, helpless, and in need of a tender hand? Or a caregiver who could love us even more unconditionally than a pet, one who asked for nothing in return but our happiness?

At the time, I couldn’t have had a pet if I wanted to. I worked all day, and my husband had allergies. I looked into buying a cat robot meant to act as emotional support for the elderly. It blinked and meowed and rolled onto its back so you could rub its tummy. I’d also considered the Japanese robot Paro, which looks like an adorable stuffed harp seal but is actually a 5000-dollar therapeutic assistance tool for dementia patients.

A friend who knew of my interests sent me a link to a Kickstarter where I could order a headless furry mound with a tail that wagged when you petted it. The marketing copy on their website read, “Stroke, React, Get Healed,” and showed a sad-looking Japanese woman petting the mound and watching it wag its tail in response, although the extent to which she “got healed” and the scope of what ailed her remained unclear. The device wasn’t available until the following year, and I wasn’t sure about owning a wagging headless pillow, so I settled on a second dog puppet, which was essentially, I realized later, a pillow with a head and tail I could operate myself.

I ordered the yellow Lab model of Blackie from Amazon and named him Waffles. He had front legs you could operate with your thumb and pinky (Blackie’s were stuffed and almost impossible to animate). Waffles used his front legs to clap when he was having fun, to pretend to conduct classical music, and occasionally to attempt to close my husband’s eyelids as if he were gently ushering a newly deceased corpse toward its final resting place. When I played with both dogs at the same time, I called it “Dog Mittens.” They were like two furry potholders with plastic eyes and black leather noses. Sometimes I made them French kiss and then felt bad about it, like I was some kind of puppet pedophile.

By obsessively searching online for other people who might like dog puppets, I discovered that if I were a fetishist, I could use them for some very dark purposes. As it turns out, I am just an enthusiast, along the lines of stuffed animal collectors and hoarders who attend Furry conventions but leave their loved ones at home for fear of being mistaken for perverts. When I asked my husband if he thought I might be a non-sexual plushophile, he said I was reading too deeply into this whole thing.

I disagreed with his assessment. My dog puppets had become a significant part of my home life, and I wanted to understand why. They served as part pet, part entertainment, and part mental health apparatus — an analog version of the therapeutic robots I’d discovered online.

At the time, I’d been seeing a therapist for two years for anxiety. But once, I noticed on the invoice she’d listed my condition as dysthymia: persistent depressive disorder. It was the first I’d heard of PDD, which is like depression but with less severe and longer-lasting symptoms. Sufferers of this type of melancholy may experience feelings of hopelessness and emptiness, but think it’s just a part of their character. The symptoms, which include avoiding social activities, were forming an outline of a woman I recognized — a woman who stayed home and played with her puppet.

Maybe my indefinable longing was a chemical imbalance and my puppets were helping me through a rough time. Maybe this was all totally normal and fine. Maybe it was even something worth celebrating. At least, that’s how I found myself addressing imaginary critics. Deep down, I must have thought there was something fundamentally wrong with me, or I wouldn’t have constantly searched for an explanation as to why I played with Dog Mittens every night — beyond the simple fact that it brought me joy.

•

One limitation of using a stuffed animal puppet as your DIY care-bot, I learned, besides making your arm tired, is that it can only love you as unconditionally as you love yourself. But an advantage is that a puppet is actually capable of love, as opposed to just having a programmed sequence of behaviors meant to imitate it.

I was lying in bed with Blackie one night when he lifted his head, turned it straight toward me, and said, “I love you, Mama.”

The declaration startled me. I had no idea I was capable of such an expression of gentleness toward myself.

“I love you, too,” I told him.

Later, when I casually mentioned this to my therapist, she suggested I bring him to a session. I could never settle on a good time to pack Blackie into a bag, take him on the subway, and keep him at work all day, so I put it off. I thought he might get dirty or stolen or I would have an uncontrollable urge to play with him at the office. Plus, traveling with a stuffed animal gave me anxiety. It reminded me of losing a beloved comfort object as a child — the moment I realized I’d left Rodney the Reindeer in the taxi, Christmas would never be the same.

Being fairly attached to Blackie, I also worried about how I would feel if my therapist reacted to him in the wrong way. Once, I’d brought a large stuffed Panda I’d gotten for Christmas from my husband, complete with a big red bow, to my parents’ house for the holidays. I celebrated by tossing him up into the air and spinning around in a circle below.

“Well, this is new,” my mother said dryly, before continuing on with her crossword puzzle.

My therapist practices AEDP, a type of psychotherapy that aims to find untapped reservoirs of strength within subjects, so they may draw upon them to deal with difficult feelings. The practice is centered on the idea of “undoing aloneness.” It encourages a safe space for subjects to experience all of their emotions and embody their most authentic selves. Perhaps my therapist could sense that my most authentic self had, at some point, been repressed, and that my untapped resource could be tapped by covering one of my hands with a furry sock in the shape of a Lab puppy.

It actually took a few months to ready myself emotionally for puppet therapy. That morning on the subway, I noticed a man peering into my tote bag. Blackie has a fairly realistically shaped body — the advantage, I think, of the stuffed animal-puppet hybrid model over one that looks like it could be a cover for a nine iron. I put my hand firmly over the outside of my bag so no one would see my most authentic self at nine a.m. on the C train. All day at my office, I glanced over at the tote, a deviant grin spreading across my face at the thought of my secret friend lying in wait. That evening, I arrived at therapy and finally let Blackie out.

“I brought someone,” I said. My therapist looked genuinely excited.

I sat down on her sofa, and he perched on his hind legs, wagging his tail such that it thumped against the upholstery.

“Well he’s adorable,” she said. “Can I pet him?”

I nodded, and she reached toward us. But something must have scared Blackie, because when her hand went for the top of his head, he opened his mouth and bit her — hard, for a dog with human fingers as teeth anyway. At the time, I thought he was just being protective. He wasn’t used to receiving acceptance from the outside (or the inside) world. Afterwards, I felt guilty about this and later apologized. My therapist said it was okay — any self-respecting dog would have done the same.

•

For me, the question remains: How does a person who is constantly pushing people away “undo aloneness”? The urge for solitude is not in and of itself unhealthy, but I suppose what one does with it can be.

Like a dog chasing its tail, I often find myself chasing negative thoughts. Because they’re there, I keep following them, as if the exercise might result in something other than additional self-criticism. Perceiving one’s self through a kaleidoscope of negativity is a downward spiral, a dizzying kind of misery to which my dog puppets provide an effective, albeit unusual, antidote. They’re me, but in disguise, which makes it much harder to criticize what they do or say, and even how they look. For instance, when Waffles gets “back rolls” from his fabric bunching up, he covers his eyes with his little arms, embarrassed, but I secretly think they’re cute.

Maybe loving a puppet can be a proxy for self-compassion.

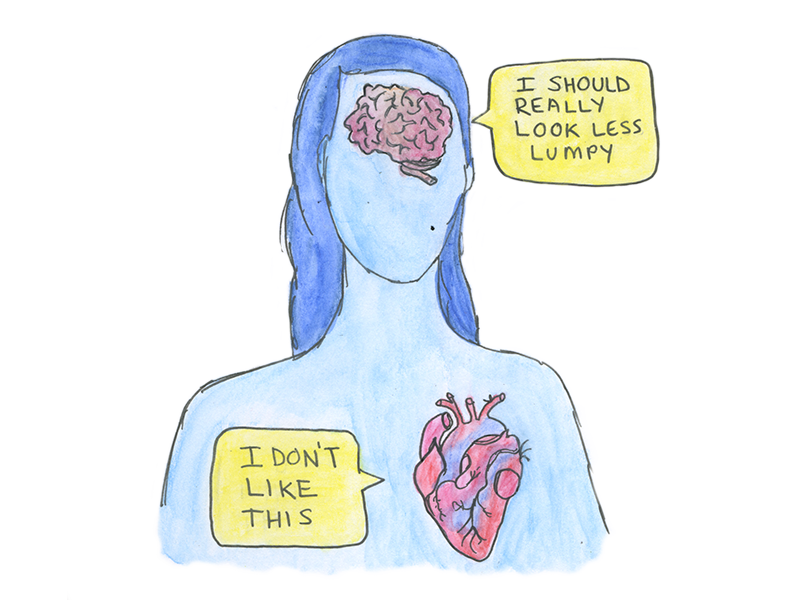

Sometimes I treat Dog Mittens like wayward children. Other times, they bring out my own inner child. It makes me wonder if part of my desire for alternative motherhood is the urge to re-experience childhood, in all of its helplessness, from a place of power. When my husband and I are watching TV, Blackie will get bored and suddenly cry out in a high-pitched voice, “I don’t like this!” He then looks around as if expecting one of us to change the channel, which we inevitably do. It’s not really rude because he’s a puppet and doesn’t appear to know any better. He not constrained by the same veneer of social etiquette that I am.

Recently at a Pilates class, I was getting sick of doing stomach crunches when I heard Blackie’s voice in my head clearly say, “I don’t like this!” I reflexively looked at my right arm to find my hand naked. I realized that the sentiment would sound pretty ridiculous coming out of the mouth of an adult woman who had voluntarily signed up for the class. Still, the voice had a point. I actually hated working out, and could pin most of the reasons I attended on decades of thinking some iteration of the same thought: I should really look less lumpy.

Maybe Blackie carries my pent-up rage and therefore feels the need to bite on occasion. He is certainly a catalyst for honest emotion, which is one way of undoing aloneness. After all, there’s nothing lonelier than carrying around bottled-up feelings. And though I’d like to think he’s being playful when he bites my husband, it often carries the same undercurrent of rage that drives the semi-maniacal act of tickling. He doesn’t think; he just bites.

Sometimes my husband and I play with both puppets together. Since I started bringing them out of the bedroom with our pillows for TV time, he’s taken a liking to Waffles.

“Everyone gets a dog,” I’ll say, swinging my black Lab by the foot and tossing the yellow one at him before plopping down on the couch to get comfortable. (Again, there are only two of us, but it feels good to point out when I’m being an egalitarian.) We watch television while Blackie lies down on my lap wagging his tail and occasionally lifting his head up to look around before resting his chin on his front legs again.

Waffles is kind of a spaz, so he tends to spend a lot of time flying through the air, guided by my husband’s arm, his front legs spread wide like an airplane. He likes to look at himself in the mirror that hangs on the wall next to our leather sofa, opening and closing his mouth awkwardly as if he is trying to extricate peanut butter from the roof of his mouth with his tongue. From my viewpoint at the other end of the couch, I get a fuller picture. It’s an alternative portrait of togetherness that addresses my indefinable longing, although I’m not quite sure how. For now, I think I’ll stop asking questions and just let the puppets work their magic. •

All images created by Isabella Akhtarshenas.