RA: Is it unusual for someone to clerk for a Supreme Court Justice [Sandra Day O’Connor], then be a criminal defense attorney?

JF: Yes, it’s unusual. It’s not unheard of. There was somebody else actually clerking my same year who ended up going to the public defender service in Michigan and is still a public defender, but it’s unusual.

RA: So, when did you decide in your law career that criminal would be the sort of law you do?

JF: It was an evolution. I went to law school thinking I would do civil rights work. When I got to law school, I worked for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. At the time, they had a unit in education, housing, employment, voting rights, and then one unit in the death penalty. I got assigned to that just randomly.

I started getting involved in death penalty cases. I just felt a real emotional connection to the issue, but they didn’t have a broader criminal justice portfolio. When I was working as a law clerk, I worked as a law clerk for a judge in Los Angeles on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals after graduation and then for Justice O’Connor. In both those years I saw so many appeals on habeas corpus: People that have been convicted in state court and now they’re in federal court trying to get their conviction overturned. They were often saying that their lawyers were ineffective. In many cases, it seemed clear to me that they were.

The standards that the court had set were so high to get a conviction reversed on those grounds. The courts would say things like, “The trial is the main event. Come complaining to us on appeal and on habeas, trial was your chance to prove you’re innocent.” It increasingly felt to me like if that’s what the courts are saying is the main event, then this is a system that seems unfair to me. Then let me go fight it at that level.

RA: Now it’s more common to associate criminal justice and civil rights, but when you decided you were interested in civil rights, you’re going to criminal justice, it wasn’t as clear a line. Is there any incident that made you see so clearly the way to pursue civil rights would be through criminal justice?

JF: There’s a bunch of things. I don’t know that I could say that there’s one incident. Part of it is the death penalty was understood as a civil rights issue. To me, the relationship between the death penalty and the rest of the criminal justice system seemed obvious. It seemed like the same things that were unfair that led people to get the death penalty also might lead you to get life without parole or might lead you to get ten years or . . . I was honestly shocked that it wasn’t on the civil rights agenda. Once the death penalty is, why not the rest of the system?

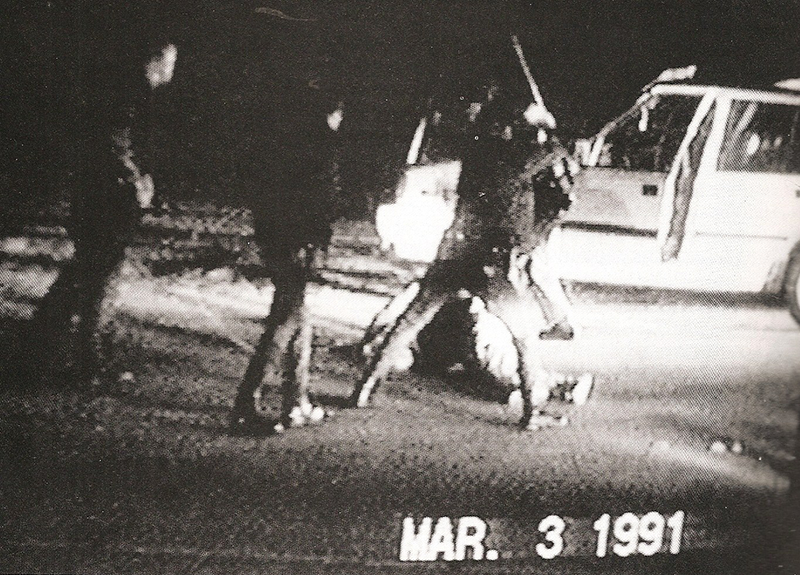

In terms of particular incidents, when I was in law school, the Rodney King video was released. Then there was the subsequent state court trial and acquittal. Violence had consumed Los Angeles. Everybody in the African-American community has long talked about police brutality. When he was on video and the officers were caught, I just assumed, everybody assumed, that they would be convicted.

Now there are more and more videos and sometimes people were convicted, but this was the first one. When they were acquitted, that just seemed to me that the racism with which the officers treated Rodney King, how they beat him, the racist comments they then made on their police scanners afterwards, that was a direct civil rights connection to me.

Then, the Sentencing Project, the D.C.-based advocacy group, issued a report when I was law school saying that one in four young African-American men is under criminal justice supervision. That was the first report. We didn’t have the term mass incarceration at the time. That was the first report that really was documenting the scale of it.

RA: Had you thought about the numbers?

JF: No, I had thought about it in individual cases but not the community-wide impact. It had never occurred to me.

RA: Here you are in the criminal justice system in D.C., thinking you’re going to do civil rights law. At a certain point, you have an epiphany that the system you are involved in is largely administered and presided over already by people of color.

JF: I had the case that I write about in the book, the young man named Brandon, or who I call Brandon because I change their names to protect their privacy. He was facing gun and marijuana charges. The black prosecutor was asking for him to be locked up. His African-American defense lawyer was asking for him to be released. He’s African-American, as were almost all of my clients. The African-American judge is the one who has to make the decision, the African-American court personnel.

When the judge locked him up, which he did in that case after reading him the riot act, what we call the Martin Luther King speech where he told him that Martin Luther King had died and fought for his freedom and it didn’t include the freedom to be running and thugging and gunning and carrying on and embarrassing his community, that really made me realize, step back and say, wait a minute. Then I thought about the fact that there are laws that Brandon had been sentenced under that were passed by a city council that was majority African-American and the mayor who signed them was African-American and the police force was majority black and the police chief was black. All the corrections officers at the juvenile jail where he was going to be held were black.

I really started to think about the fact that there is a story that needed to be told of what was going on in this community over the last 40 or 50 years that would lead people to be like the judge, because the judge wasn’t alone. There are a lot of people who thought like him. We went in and faced hostile judges all the time. We often would remark on the racial issues. I wasn’t the only one in my office to say this is crazy. Why don’t these people see what we see? That’s the way we phrased it at the time. As public defender, you have to be righteous. That’s your stance towards the world. It just is.

That really pushed me to think there’s a story to be told. Then when I became an academic, I realized that nobody had told it. I realized that there wasn’t a book that had been written that tried to explore with nuance and subtlety and historical sensitivity how this came to be.

RA: To return to Brandon, on one level, he only gets a six-month sentence. But what does that potentially mean for him and people like him in terms of their future?

JF: You look at similar situated kids, similar situated background, one of them gets probation, and one of them gets locked up. There’s really powerful evidence now that being incarcerated as a juvenile, even controlling for other factors, dramatically increases the likelihood that you will not graduate from high school and that you will get rearrested and that you will be arrested and convicted of a crime as an adult.

When I was a kid they had Scared Straight, but that doesn’t work. The empirical evidence is overwhelming that it’s not Scared Straight, that what it does is it takes you off track. It does all sorts of things. It’s traumatic. It introduces you to people who have more serious criminal histories than you do. It tells you that you are a lower person and that you are not somebody who has potential, that you’re somebody who is supposed to be and destined to be behind bars.

Then, in a very concrete way, the schools that exist in our juvenile facilities are typically — although some people are working to improve this including a good who I mention in the book, but still — typically are terrible, awful places. The violence is rampant. Drugs are plentiful. Your actual experience while you’re incarcerated is pushing you further and further and further down towards a criminal trajectory and further and further away from an education, employment, meaningful life trajectory.

Then you get released, and principals in a lot of schools don’t want to take kids back who have been incarcerated. They figure that kid is just going to bring a bad element to my school, and so they come up with ways to try to discourage them from re-enrolling: you’ve missed too much time, you’re going to be held back a grade. They’d counsel kids out of the schools. Then they get shunted into alternative schools, which in theory, if they were well-funded and well-run and robust places, could be good opportunities, but by and large aren’t.

Again, we’re speaking in generalities here. There’s an exception in all of these cases. As a general matter, what it means is you have this traumatic event, you get ripped from your family, you get exposed to violence, you get uneducated and miss-educated, you get beaten, then you get released. It’s harder for you to get back in school and you feel like a failure and everybody’s told you you’re a failure. Then you start hanging out with kids that are up to no good. Then you commit another crime, and now you’re a repeat offender.

That’s the general trajectory that starts this. Not to some eyes. I don’t think the judge in that case, he didn’t see himself as being excessively punitive. But that’s what that creates. It’s an aspect of what people talk about when they talk about the school-to-prison pipeline. That’s one component.

RA: How much of this is drug war convictions?

JF: In the federal system, it’s more than 50 percent. A lot of the numbers people draw from are the federal numbers. That’s why sometimes people say most prisoners are drug offenders. They’re talking about federal system. The federal system is a tiny aspect of our overall criminal justice system. Eighty-eight percent of prisoners are in state and local and county prisons. Most of them are there for offenses that are labeled violent offenses or property offenses.

Now, the drug war, in some sense, contributes to some of those offenses because once you make drugs illegal, then you’re involved in the drug trade. Then you’re more likely to carry a gun, and then you’re more likely to resolve a dispute using the gun. There’s a way in which you can say that the drug war contributes to more than the share of offenses that we just label as drug offenses.

Having said that, I think the drug war is a problem, but I actually resist the idea that it’s mostly or mainly the drug war. I think that then we miss the ways that we became harsher across the board, including to people who commit robbery or armed robbery or burglary or gun possession.

RA: You trace this back to the ’70s. What made us go from the idea that prison is to be rehabilitative, to put people back out on the street as better citizens, to if we lock away a problem for 20 years we don’t have a problem?

JF: It’s a complicated range of factors that lead to that. A lot of what’s happening is at the national level. Nationally, you have politicians like Goldwater and then Nixon who are using crime as a way to drive a wedge between the traditional Democratic voters and win the South. You can’t be explicitly racist anymore. That doesn’t work. You use crime as a way of talking about race. That’s an argument that lots of people developed and is true and is accurate and is part of the background that I incorporate into my story.

RA: We call this the Southern strategy, right?

JF: Exactly. That’s going on. You also have crime rising. Crime rises very dramatically in the 1960s. Washington, D.C., the homicide rate triples. In lots of other communities nationally, it doubles. Heroin addiction really sweeps through the community. In D.C., for example, they tested people for heroin when they entered D.C. jail, all arrestees that were being brought into the jail. In the ’60s, three percent tested positive for heroin. By 1968, it was 45 percent. That’s an epidemic.

People are becoming addicted to drugs. The people are committing crimes to support that habit. The homicide rate is going up very dramatically. People are scared. A lot of what I write about is to really try to make people understand that particularly when you focus on African-American communities, there was real palpable fear in those years. I came across letters from people saying, “I feel like a prisoner in my home. I feel like a stranger on my streets. I don’t know what’s happened to my city.” They’re pleading with their local elected representatives to do something about it, and then again, focusing on the part of the story that I’m most interested about, which is looking at how this happened in black communities and among black elected officials.

We have to take into consideration the fact that the people receiving those letters, on the receiving end of those pleas, were this first generation of African-American elected officials that came into power after the decline of formal Jim Crow. Many of them knew of the long history. Today we talk about over-punishment, but there are hundreds of years of under-protection, where you didn’t call the police in a black community when somebody was robbed or somebody was stabbed because they weren’t going to come. If they did, they were going to make matters worse. The famous line among southern sheriffs: That’s not a homicide, that’s just another dead black person. They didn’t say black person.

Against that history of under-protection, now imagine that you get into office. You are an African-American official. You have some control now over the police department and over the prosecutor’s office and over the criminal justice apparatus. One thing you want it to do is you want it to be responsive to those claims of black victims. That’s one of the things that people try to do.

The second chapter of the book is called “Black Lives Matter” — the idea that we want to make black lives matter and we want to increase criminal policing prosecutions and punishments so that people who are harming black people are put away. This is very present in the 1970s with this first generation of politicians. That’s another big piece of the story.

RA: Actually, I was going to ask you about Eric Holder.

JF: Sure. Eric Holder, I think, to me he’s a really good example of this story. Eric Holder has done tremendous work in his career on behalf of African-American people, all people, but on behalf of African-American people in particular, on racial justice issues recently. He’s famously and publicly led the effort to try to roll back some of the harshness in our federal system. Now that he’s in private practice, he’s doing incredible work on voting rights. He also did a lot of work on juvenile justice reform over the scope of his career. Any discussion of him has to include those components.

He’s not someone that doesn’t care about black people.

RA: Not a villain. Not an easy villain.

JF: Far from it. He’s not a villain. He, in 1995, as U.S. Attorney, comes in at the tail end of the crack years. He gives a speech and he says that the black people of Washington, D.C. are no freer than were the black people of Selma in 1955. That’s a big deal when you invoke Selma in black America.

His argument was then that we were being kept down by segregation and Jim Crow and now we were being kept down by crime and violence. We talk about the new Jim Crow, but he was in essence making the argument that crime and violence is the new Jim Crow. It’s analogous to that. He didn’t say that explicitly, but that’s the import of his argument. He then said, So, what are we going to do about it?

Here comes additional complication. He wanted to do lots of things. He talked about root causes. He said we can’t arrest our way out of the problem. I truly think that he believed that. I don’t think it was lip service. He was a prosecutor. He was facing an emergency. What could he do? He didn’t control the federal government. He didn’t control the school system. He did have influence over the criminal justice system.

What he initiated was this thing called Operation Ceasefire. There’s versions of this with that title in almost every city. It’s a very common name. In D.C., what it meant in the 1990s was we’re going to pull you over on any pretext that we can find for a traffic violation; tinted windows, broken taillight, expired license, driving too fast, driving too slow, changing lanes without signaling, stopping at a stop sign not long enough, stopping at a stop sign too long, and so on and so on. Famously, every police officer says, give me 60 seconds, follow anybody — I can find a valid time that they violate the traffic laws.

Holder said though, let’s focus that enforcement on guns. He was trying to get guns off the street to respond to these skyrocketing violence levels of the crack era. That’s what they did. They officially exempted the one part of the city that most white citizens lived in. This was a program that, by design, was going to focus on black people. It was also by design focusing on the area where gun violence was highest. That’s how it was rationalized.

What happens if you stop all of these cars and all of these people and then you do what police are well-trained to do, you scope out the car as you’re walking up to the driver? Then eventually you engage in a conversation that leads to the request to search the car, which over 90 percent of people consent. The police are not required to tell you that you have the power not to consent. Most people don’t think that they do.

What happens if you search all these cars? You get some guns and you also get a bunch of other stuff including marijuana, including small amounts of marijuana, which you would never stop somebody . . . no officer’s like, “I’m going go stopping cars because I want to get $10 or $15 or $20 worth of marijuana.” Police officers don’t want to waste their time doing that. Having stopped you, and having encountered it, they don’t have the discretion to decide which laws to enforce and which laws not to enforce. The officers then book you for the arrest. Maybe later a prosecutor dismisses the case. Maybe, if you don’t have prior record.

One of the people that I write about is a woman — her case is dismissed. She has no record. I bet if you were to ask a prosecutor at the time, they would have looked at that as a success because they would have said, “Listen, the system worked the way it was supposed to. We’re going after guns. Yeah, we had to arrest her, but she was given a citation, a notice to appear in court. She didn’t miss any work the next day. She wasn’t held overnight in a jail, and a prosecutor eventually dismissed the charges. She had to spend a few hours in court and then the case was dismissed.” But turned out she had to get a certificate of clean record to get off probation with her employer. When she applied for it, it came up that she had this arrest. She was promptly fired. To me it’s just a classic example of the tragedy of the system and how you have all these different actors.

When Eric Holder stood up to announce Operation Ceasefire, he didn’t say, and I don’t even think he thought, “A woman working for FedEx with no record and $20 of weed in her glove box is going to lose her job and maybe not be able to provide for her child because of my new announcement.” He was focused on the target, which were the guns. This is how the dysfunctions play out across systems. Then when you bring in private employers who now have this increasing access to technology and can get any record with the push of a button on anybody they’re considering hiring. That’s how an initial decision like that one can lead to these down the line really devastating effects.

RA: Do you there was a moment when Holder realized, or was it a slow process of him moving towards criminal justice reform?

JF: I don’t know. I suspect the latter. I doubt that there was a gotcha moment. We sometimes remember moments or we’re sometimes asked about moments. You started the interview and you said, “What was the moment when you realized that you wanted to become a public defender?” We ask ourselves that. Sometimes we do boil down, and we’ll remember things down to a moment. Of course, it was accumulated.

Even the story that I tell about Brandon, that was a moment. It was a process of going to court and seeing various African-American actors, having a jury. I had in one case where the jury was split 11 to one in a murder case. They were out deliberating for days. In D.C., as a lawyer, you might see the jurors. There were 11 people all together. There was one guy by himself, separate every time they would come in and out. They were deliberating for five days. It went on and on and on.

The 11 people who were together were ten African-Americans and one white guy. The guy who was by himself was white. My co-counsel and I were absolutely convinced beyond that it was 11 to one for acquittal and that white guy was the holdout. They could not reach a verdict; they hung jury. I can’t remember if the judge polled them or we interviewed them. Either way, we found out that it was 11 to one, but it was 11 to one for conviction and the one holdout was that white guy who was hanging out on his own.

I didn’t go on my next jury and then try to get an all-white jury. I’m not saying that. I’m just saying that instances like these all come together to complicate things. Then you boil it down to an incident like the Brandon incident. I suspect for Holder it was the same thing. I bet it was accumulated.

He’s an incredibly smart guy, and I suspect a voracious reader, and especially in the last five years, there’s been so much writing about the criminal justice system and the toll that it’s taking. I think that he got in there, and I think he just started to see things. Then he had the power to do something about it. He had a president, a boss who was willing to ride some of that with him. I think that’s what happened.

RA: When you talk about the tremendous consensus, obviously, I don’t think Jeff Sessions had been picked yet to be the new Attorney General back when you sat down to write this book. It seems that that consensus that we seem to be moving towards in your book, is suddenly not a consensus at all anymore. In fact, the view is we need to go back to the policies that you seem to passionately believe are a disaster.

JF: I don’t think the consensus has changed as much as Senator Sessions, his selection, and his pronouncements would suggest. I think the crucial thing to remember is that this is a system that was built overwhelmingly at the state and local and county level. Eighty-eight percent of prisoners are in state, local, and county facilities, not federal. Eighty-five percent of law enforcement is state, local, county law enforcement, not federal.

The fact is, whether Philadelphia is going to have a more progressive approach to criminal justice and reduce the size of its prison and prison population and emphasize restorative justice turns much more on who’s elected for district attorney in this city than on anything that Jeff Sessions or Donald Trump does.

This is created at the local level and it has to be solved at the local level. It doesn’t mean that the federal government doesn’t matter. Of course it does.

RA: They offer money to partnerships in the area as they think enforcement should be.

JF: That’s right . . . I think it’s a mistake for people to become resigned. I’ve seen way too much in my mind of people . . . I guess resigned is the right word, saying, “That was a good effort, but now Sessions is going to undo it all.” He’s going to undo it all if we let him. He’s going to do some damage. There’s some damage he’s going to do that we can’t control. He says things like, he said, “Marijuana is only slightly less awful than heroin.” That’s a line that could have been taken from somebody in my book in 1975, and now we know a lot better and a lot more. Last year there were 13,000 deaths from heroin overdoses. There were zero deaths from marijuana overdoses. He is going to say uninformed things.

RA: He would then say all 13,000 of those heroin overdosers probably smoked pot first. That is the argument that goes back to Jackie Robinson.

JF: Maybe he would. They also ate popcorn before they used heroin. I think the movement for reform is broader, is deeper, and is more local than focusing on Trump or Sessions gives credit for.

The same election that brought Trump and Sessions led to a slate of progressive prosecutors. First of all, the notion that you would run for prosecutor, the most powerful position in our criminal justice system on a platform of we’re locking up too many people; we need to decriminalize small amounts of low level drugs; we need to challenge the death penalty; we need to focus on police brutality and win was an unheard of thing. It’s never happened before at this scale. Folks won in Denver, Colorado, in Houston, Texas. A guy in Fort Worth, Texas, a former defense attorney with the words “not guilty” tattooed on his chest, challenged the incumbent D.A. and won.

I don’t think the Trump election was about rolling back this reform effort. It wouldn’t have been the case that these progressive election results would have happened at the same time had that been going on. •

Feature image courtesy of ATOMIC Hot Links via Flickr (Creative Commons). Other Images courtesy of ATOMIC Hot Links, The Aspen Institute, and Michael Gil via Flickr (Creative Commons)