There are few cartoonists in North America at the moment that have garnered as much esteem in the literary realm as Chris Ware. The back cover to his latest book, Rusty Brown Vol. 1 contains plaudits from such folk as David Eggers, David Sedaris, and J.J. Abrams. His art frequently adorns the cover of The New Yorker magazine. His work has appeared in The New York Times and he’s gotten to collaborate with folks like Ira Glass and exhibited at a Whitney biennial. He has, in effect, made it.

Of course, that depends on your definition of “making it.” The drive for acceptance in the big, bad world of book publishing that pushed so many alt-cartoonists in the ’80s and ’90s seems to have dissipated now that it’s been achieved and Ware, standing tall amidst his peers, seems ripe for pot shots. There’s a tendency by some critics to view his work as aloof or cold due to his ultra-precise, geometric drawing style, or perhaps conversely as too “depressing” due to the isolation and despondency that most of his characters go through.

I tend not to regard either assessment as having much depth or merit. This is not to suggest, however, that Ware’s work is somehow immune to criticism — Rusty Brown has moments of sheer genius but some missteps as well. Rather, I find it interesting that the sort of earnest, slice-of-life work that Ware has staked his claim in has fallen somewhat out of favor as the indie comics scene has grown and expanded.

But perhaps before delving into the book itself, I should talk a little about why exactly Ware is so well-regarded. Even when Ware first came upon the indie comics scene in the early 1990s it felt like a shock to the proverbial system. Who the hell is this guy who created such striking, formally daring work that seemed of a piece yet completely alien from what anyone else was doing at the time?

In the pages of the seminal Raw anthology and then later in his own one-man anthology series, Acme Novelty Library, Ware played with the format constantly, putting the text and images at seemingly disparate odds against each other in stories like “I Guess,” or designing sequences that seemed more like ornate diagrams or flowcharts than your average comic book page. Even the size of the comic would shift from issue to issue, going from a gargantuan “how am I going to get this on my bookshelf” to something that could ostensibly fit in your back pocket. Even the lettering, filled with ornate flourishes recalling early 20th-century advertising, was unique.

Inside those issues, Ware would tell darkly comic stories of ne’er do wells and others lost at sea. Socially awkward, lonely (and perhaps even rather dim-witted) men (and the occasional anthropomorphic animal) battling against their own inadequacies, poor parental figures, death, and illness or even God himself (usually dressed up as a superhero).

It all came to a head with Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, a graphic novel that leaped back and forth across the decades to tell the story of the title character — a nebbishy guy who meets his birth father for the first time, and, alternately, the abusive and difficult childhood of the grandfather he never knew.

Published by a “legitimate”, big-name book publisher — Pantheon — Corrigan garnered swaths of attention and praise from the mainstream press and won several notable awards. Thus, the book became the vanguard in the “Hey, comics have serious literary merit” debate, one that actually broke through to academia as well as folks that read . . . well, the New Yorker. And Ware quickly became regarded as the “one of the great living cartoonists,” a badge the self-effacing Ware probably views as a mixed blessing.

Ware has followed up Corrigan sporadically — his books are ambitious and large and take time to produce. Building Stories came out in 2012, a literal box of various sized comics about a lonely, disabled woman living in a Chicago apartment house. The comics could be read in any particular order, thus changing your interaction with the work ever so slightly each time you engaged with it.

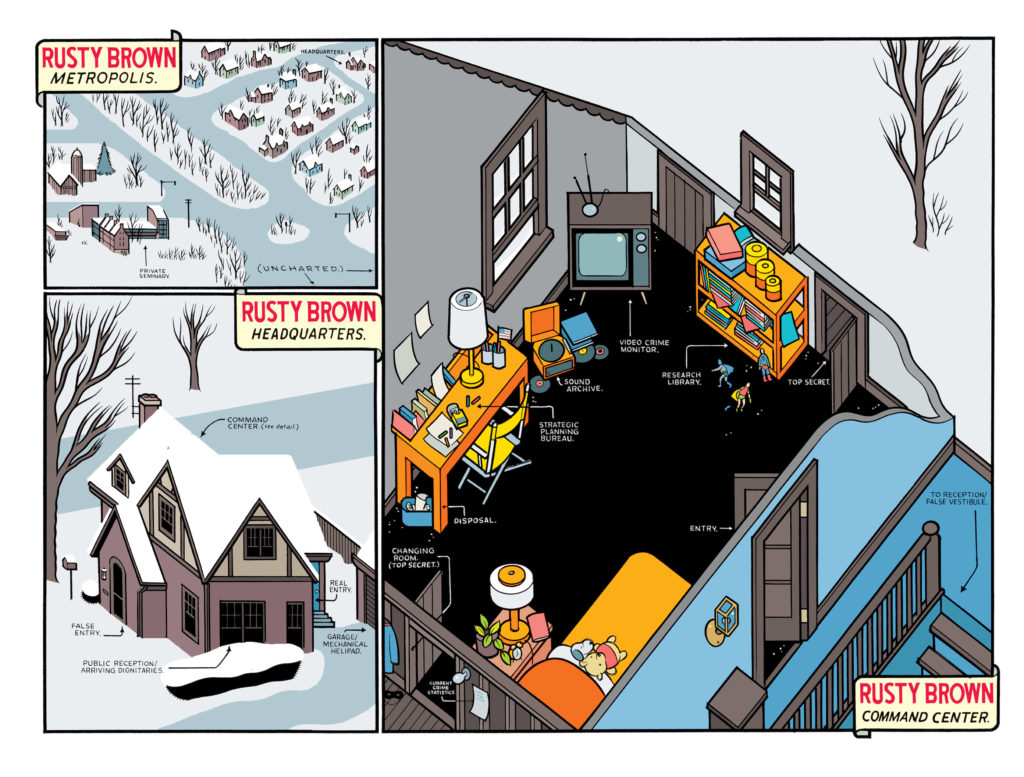

Now we have Rusty Brown, a series that began at the tail end of the Clinton era and has only reached its halfway point here in 2019. If Building Stories was a variety of books about a singular person, Rusty is a singular book about a variety of people.

The character Rusty Brown began in Acme Novelty Library as a rather savage parody of the collector fanboy type — a type that Ware, who has admittedly obsessed over ragtime music and the occasional piece of pop culture ephemera himself, knows perhaps better than he’d care to openly admit. Basically, imagine an even more pathetic and creepy version of the Comic Book Guy from The Simpsons and you’ve got the right idea.

As the book opens, however, it is circa 1975 in Omaha, Nebraska, (where Ware spent a good deal of his formative years), and Rusty is still a child, enrolled at a private elementary school, where he is bullied mercilessly by his classmates. Life at home is not much better where he is at best ignored or barely tolerated by his dad (who we’ll get to in a minute). It’s not too surprising, therefore, to find him lost in his own imaginary world of fantasy and superheroes.

But Rusty quickly takes a back seat to two new arrivals at his school: Chalky White, who we know from previous strips will become Rusty’s best and perhaps only friend, and Chalky’s older sister, Alice, devastated at being separated from her best friend and forced to live with her grandmother.

As the day progresses, we are introduced to a large cast of characters. Ware even goes as far as to insert himself into the narrative as the school’s art teacher, portraying himself as a stoned, predatory, self-absorbed jerk whose art consists of appropriating comic book images in a subgrade Roy Lichtenstein fashion. Is this Ware imagining a dark turn his life might have taken had the whole comics thing not panned out or just taking the opportunity to mock his public persona?

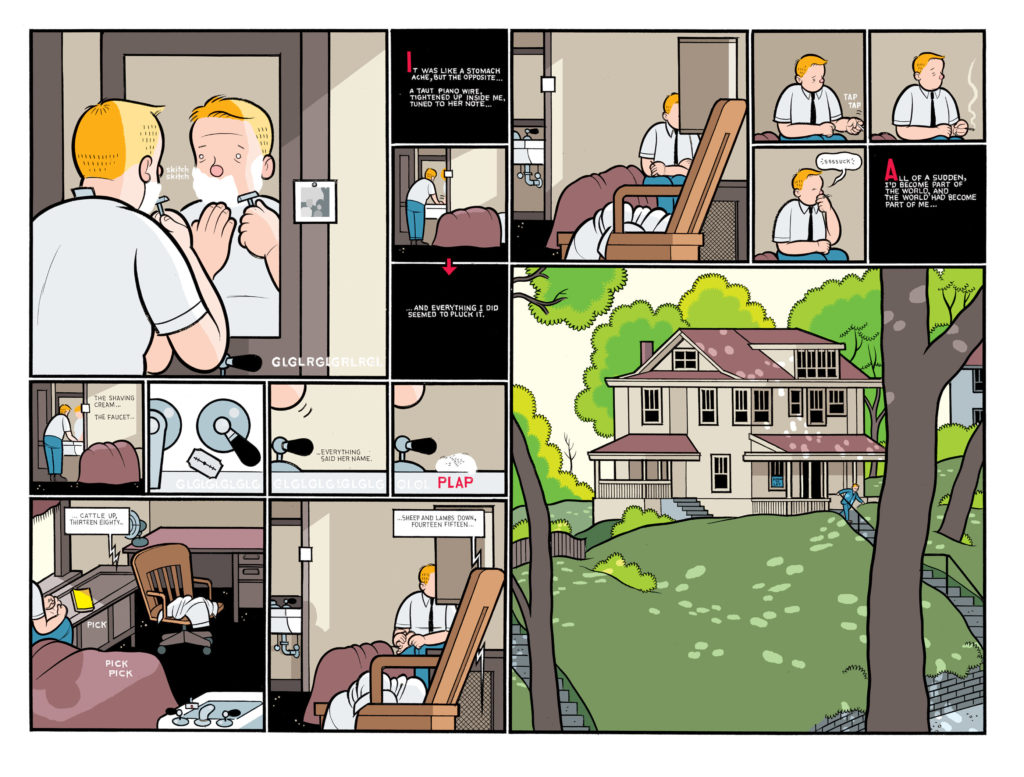

Then there is a shift in focus. It turns out that Rusty is not the central character in this book so much as the planet around which the other characters orbit, at least for this moment in time. Thus, after the introductory first two chapters, we then spin off into the inner life Rusty’s Dad, William Brown, a deeply depressed high school teacher who pines over his lost, budding career as a journalist and a science-fiction writer, but mainly the ill-fated romance he had with a coworker.

Ware begins this segment by “adapting” Brown’s sci-f tale “The Seeing Eye Dogs of Mars”, a harrowing story of a space mission gone horribly wrong, and which seems to suggest Ware could have a solid career as a horror writer if he ever wanted to set his mind to it.

From there we see the life of Jordan Lint, the teenage bully that bedevils Rusty and Chalky. And then Rusty’s teacher, Joanna Cole, an African-American woman whose quotidian, quiet life consists of navigating small (and not so small) racist incidents and comments, while taking care of her elderly, disapproving mother.

The section on Lint is — there’s no other way to say it — a tour de force, possibly Ware’s finest moment on paper thus far. With each page offering a short snippet from each subsequent year in Lint’s life (starting with several near-abstract, ben-day dot designs as baby Lint attempts to understand the world around him), he comes off mainly as a short-sighted, entitled brat with a giant chip on his shoulder (mainly due to the death of his mother and a scolding father — familial relationships are key in Ware’s work).

Lint is seemingly incapable of understanding how he is his own worst enemy or the effect he has on those around him. And yet Ware manages to develop genuine sympathy for this needy, baffling example of modern American manhood. It’s a sympathy that is sorely tested when the comic makes an abrupt shift in style (becoming far more “primitive” and expressionistic than anything Ware has attempted before) and we learn of a horrible, abusive incident in Lint’s past so bad that he might have neatly filed it back in the recesses of his brain.

There are other striking moments as well — the heart-rendering finale to Johanna Cole’s chapter, where suddenly everything snaps into place. Young Woody stumbling around Omaha, unable to see — both literally and figuratively — how toxic his would-be romance is. A simple, two-page sequence of a cardinal perched on a birdhouse in the snow, while below a garbage truck goes about its business.

You may have noticed the word “lonely” or some variation of it crop up in this review a lot. Ware’s comics frequently dwell on his character’s desperate desire for communication and acceptance and the inability to ever really make your inner thoughts — your “true” self — known. Rusty Brown’s cast is constantly clumsily — and often cruelly — bumping into each other while nursing their private pain. The few scenes of genuine warmth and kindness — as when a fellow teacher compliments Cole on her way with her students — stands out as an aberration against the meanness. Maybe that’s Ware’s point.

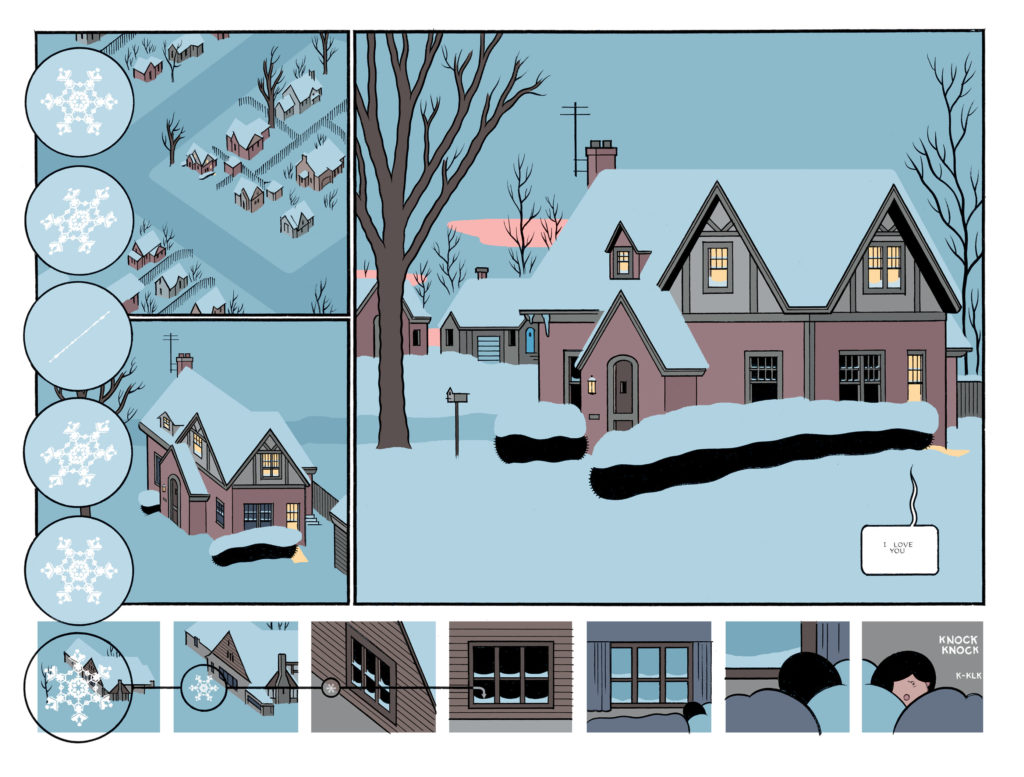

The notion of people being unable to step in each other’s shoes, of not being able to get along despite having a good reason is not an uncommon theme. And Ware does himself no favors in his opening narration, expounding on the wonder of snowflakes and drawing painfully obvious analogies to people (little could he imagine back in the late ’90s when he started this project, that that noun would become a right-wing slur against anyone that dared to care about people less fortunate than themselves).

More to the point, however, the biggest strike against Rusty Brown is that the various stories don’t ever really cohere into a complete and satisfying narrative. All the charming and emotional sequences stand apart from each other, much like the characters in his graphic novel.

That might certainly change when the second volume arrives in stores, hopefully not too far off in the future. Ware is a smart and capable enough cartoonist to be able to tie this all up neatly. And if it seems a bit churlish criticizing the book for being incomplete, well, that’s the publishing game for you.

Regardless of what Part Two will be like, there are enough exemplary parts in this volume to remind readers exactly why Chris Ware is so well-regarded. Those who accuse him of being cold, clinical or dour miss so much of the humanity, formal inventiveness and telling observation he brings to his work. I wouldn’t call Rusty Brown a slam dunk by any means &rdsquo; certainly not yet. But it is a reminder of how great he can be. •