I’m what’s left of when we

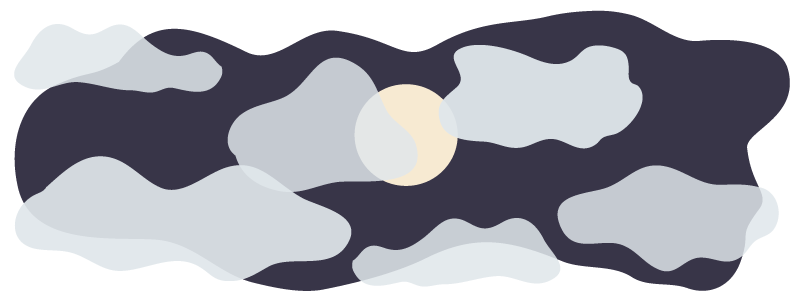

swam under the moon

-Mitski, “I Don’t Smoke”

In the summer following my completion of grad school, my boyfriend Jonathan and I moved into an apartment in East Vancouver. Our search for a home had been an exhausting dead end until the final days of June. We were driving around the city, windshield wipers on to clear the summer rain, a sense of hopelessness sweeping us forward, when we saw the vacancy sign.

That’s always how it goes — you wait in a constant state of impatience for something to happen, and then suddenly everything turns on its head. A couple had already signed for the apartment and were meant to move in the following day, but they’d had to break the lease — a domestic dispute, the landlord whispers as he hands us the papers to sign.

The apartment is on the top floor of a three-story walk-up. There are ten apartments in the whole building, all of which are empty, because the landlord says that they’ve been renovating the building for the last year.

Ghost Girls in Three Parts

“This one is the most slanted,” the landlord says as he leads us up the stairs. Towards the top, you can start to see and feel the slant. It’s like the center of the building is a spine of a book, and either side is closing up slowly towards it. But it’s the end of the month, and the floors are hardwood, and the apartment is more spacious than any we’ve seen, and there are windows and space for both of us to have desks in the living room opposite each other where we can work and fill the newly found free time of graduation and unemployment with the continued pursuit of our free-floating dreams of art and freedom. I am almost 29. We’ve both been officially unemployed for several months and living between our parents’ houses. We lie about the unemployment and write imagined salaries on our application. I offer to give the landlord rent checks upfront and we conduct ourselves in the aggressive way that’s necessary to land an apartment in this city.

“You don’t need to show it to anyone else,” we insist. After some further prodding, we follow him down to the basement to sign the papers.

I am at a turning point, one where everything feels stagnant and also startlingly clear. It’s almost like I slipped back into my body for the first time in years.

I’ve never lived with a boyfriend before. I have spent the last ten years either in school or traveling or working at a daycare. My life stretches out in front of me, but I can’t seem to get my footing. It’s been five months since Sam died. We leave the building breathless and scared, holding hands. We venture back out into the summer rain.

I haven’t been sleeping much lately. There’s this thing that happens to me at least once a week. I’ve started affectionately referring to it as my sleep disorder. I can’t put my finger on when exactly it started, but it must have been sometime in my early 20s — after I’d moved away from home and had taken up a long-distance relationship and alienated many of my old friends. The girls of my childhood drifted away from me.

It usually goes like this: I wake up in the middle of the night, and I don’t know where I am. Because I need total darkness to sleep, I can’t see anything, but I feel like I’m in the wrong place or that I’ve done something terrible, that my nudity implicates me in something bad. Because I sleep naked, I am hit with sudden and all-consuming embarrassment — that I’ve passed out at a friend’s house and stripped off my clothes in my sleep, that there’s someone next to me in the bed who’s been pushed up against my naked back all night. I sit up. I pull the blanket aside as quietly as possible. I put my feet on the floor — is that carpet? Hardwood? I haphazardly look for clues as to where I might be, but nothing sinks in past my panic.

I creep out of bed and feel around on the floor for something to put on. I stumble into jeans and sweatshirts or whatever else I can find before falling back into bed. In the morning I wake up with mismatched outfits on and vague recollections of crawling around in the dark.

This carries me through my 20s — through a first love, a loss of my best friends, a heartbreak, a relapse, a journey, a return — this fear that I’m exposed and vulnerable in a place I shouldn’t be. What is it about the night? Years ago, my friend Sam told me that at night she lost control, that sometimes it felt like she was possessed. At the time, I told her everything would be okay.

•

Teach your girl to be quiet and calm. To control her anger or give it another name — sadness, loneliness, regret. Teach your girl to white knuckle it through injustices and begin to number them, one through one million, so she will learn which ones really matter and which ones aren’t so bad. Teach your girl to protect herself and the others by downplaying their pain. Teach them it’s okay. Teach them you’re fine. Teach them it could be worse. Teach them that’s just how it goes. Teach them, out of the kindness of your heart, how to get on with it.

They will learn quickly because they are good and smart and calm and sweet and brave and have an unbridled desire to live in this world. They are conscientious. They listen. They know what’s at risk. Just don’t be surprised when at night, once the room is cleared and the clutter of the day has subsided, all that buried rage and fear and sadness and regret and loneliness comes unhinged and blooms through the rooms where she sleeps.

Listen for the slamming of the door. The curtains resettling themselves without wind. The clock flashing three a.m. The feeling that you’ve just woken from a conversation but can’t remember the words that were said.

•

It’s strange moving into an empty building. There’s more room for the echo of furniture scraping against the walls of the stairwell. There’s the sound of the front door slamming in the middle of the night. Ten different groups of people trickle into ten different apartments. Someone drops their couch in the stairwell and it gets stuck there for a day and a half, a note taped to one end that says “sorry.” The front door to the building never closes hard enough, and we realize that it’s always open. Our first home together feels full of all of the potential of a steep cliff — there could be wonder or terrible vulnerability here.

For a while, all we have in the living room is a glass-topped coffee table that belonged to my grandmother and a Persian carpet that was a graduation gift from my parents. On our first night, we buy a bottle of red wine and order Chinese takeout and sit on the floor around the coffee table, exhausted.

That night, in our new bedroom, I feel like our bed is floating out in the middle of the ocean outside the bay where Sam and I grew up. There is something open and vulnerable about a new space. Our bed feels strange and out of place at the center of the room, like it has no business being there. The light comes in unapologetically through the blinds and under the crack beneath the front door. The new sheets I bought the day before are scratchy and not breathable, so we sweat and hold each other and only talk about the things we like about the place, though the other things are palpable in moments of silence, doubt shadowing the corners of our conversation.

There are the unknown sounds at night. Voices through the air vents, another language snaking through the room while I run a bath.

I wonder who lived here before us. I wonder what a year of emptiness does to a space. For the first time in a long time, I start to think about ghosts.

Once, in Italy, there was a ghost at the foot of our beds. Rose and I, halfway across the world, alone on the top of a mountain. When we were kids, we pleaded for ghosts for years. Sam and Audrey had seen one together, perhaps it only made sense that Rose and I saw one together, too. We were alone in our beds, but not separate. It took us days to talk about it. Not out of fear, really, but just out of the sheer fact that life continues on whether you want it to or not, whether something happens or it doesn’t. Sometimes storylines play out over years, and you can’t see them clearly until they’ve long passed.

On a train to Milan, I told Rose that I’d felt someone in our bedroom in the farmhouse on the mountain. Me too, she’d said, and gone on to explain the landscape of the dream she’d been having when the ghost appeared at the foot of our beds. Something or someone had been dragging her across the room, and she’d been fighting to pull herself back. She could see me and was calling to me for help. I’d heard her, in the dark of the room: Don’t let them take me, she said.

I’m so glad that we were together.

If childhood was a time to challenge all our fears, to scream at them and taunt them and draw them in, unafraid, then my early 20s was when they heeded the call and started to appear. Nothing’s what you think it’ll be — I was oblivious and unafraid when the ghost appeared, when I woke up in strangers’ beds, when my family started falling apart, when my childhood friends started drifting away. It’s the aftershock that you have to be wary of.

In all honesty, sometimes I forget these things even happened.

In our new apartment, I dream of my childhood home, the three-story wood-framed house on the water that my parents built after years of imagining it, on the land that my grandfather bought in the 1940s for pennies.

A confession: the dreams are never sweet, fruitful, home dreams. I can’t dream of that place anymore in any kind of gentle way unless it’s gently dark or gently frightening. The feeling of being young and living there lurks in my brain like a snake under water.

It goes like this: There are six entryways to the house. In my dreams, it’s always nighttime, and I’m walking from door to door, making sure everything is locked.

Sometimes, as a teenager, I’d come in late and the lights would be low, and this is what it looked like. The chairs pushed in neatly to the cleared dining room table, fireplace embers gone cold, the sitting area near the side porch completely dark, the piano a silent mass in the corner, the buzzing of the dim light over the center of the dining room table and sometimes in the kitchen to the right of it. My parents were always home but this sometimes felt like the only time I was alone in the house, even if they were upstairs in their bed. I knew where to step to avoid creaks in the floor. I knew which windows to avoid: the ones that would reflect my nighttime self back like an intruder, bare feet and a glass of milk in hand. This is where my dreams take place, in this alone space.

Before going upstairs, I double-check every lock. This habit has stuck with me through life. We never locked our doors during daylight hours, that habit was learned once I’d moved to the city, but at nighttime it was imperative. This always seemed somewhat futile to me as the doors in the house were all partly glass, and if someone wanted in, there was only a rock between them and us.

Every time, I get to every lock but the last one. The front entrance. I walk quickly towards it, and I know that it’s unlocked, that someone is standing on the other side. Inevitably, when I reach for it, someone is pushing it open. We struggle at first, pushing against each other. Nothing too forceful, something that could be mistaken for a friendly foul. You called me. You invited me in.

Sometimes I see a face. Once it was a woman I used to see downtown at various bars, someone that an old friend had brought into her apartment one night as I sat on her bed and tried to decide the direction my night would take. The woman walked in, and I was struck with paralyzing fear that didn’t let up until she exited the apartment. She was no one I knew, just a common sickly pale face, tall and self-aware in a way that made her slouch to hide her height. Once it was a boy I knew from elementary school whose dad was an alcoholic who sent him to school without lunch. I paused and looked at him in the dream, said I didn’t know you were still around. Sometimes there was no one there, just the feeling of being unable to keep the bad things out — the monsters and murderers and exposed hearts and long lonely nights. They howl through the door like the wind during the summer storms that used to hit the bay when I was a kid, when I used to dangle my bare legs out of my window and watch the grey sky swell into a navy bruise. The door opens, and I wake up.

I’m home alone in the new apartment when the buzzer rings unexpectedly. I press the button of the intercom and a woman’s voice emerges.

“I used to live here,” she says. “Are the floors still slanted?”

“Yes, they are.” I try to picture what she must look like, but my mind draws a blank.

“They were supposed to fix that. No one’s supposed to live here. They kicked us all out because no one was supposed to live here. They said they were tearing it down, structural renovations.”

“Oh,” I reply, a cold feeling spreading through my gut, “They renovated some of it. The appliances are all new, and the bathtub . . .” I trail off.

“They kicked out families with kids, you know. People who’d lived there for 20 years. They said they were tearing it down.” Her voice escalates steadily with panic. I consider going downstairs and talking to her outside the door, but I decide against it and instead recite the building manager’s phone number to the disembodied voice. She thanks me. We wish each other luck.

•

Sam and I grew up on a sheltered bay that looked out onto the forever of the Pacific Ocean. We spent days swimming the water or trekking through the forest with our other best friends, Audrey and Rose. At night, we’d sleep in the tent on Sam’s porch with the fly off so we could see the stars.

Near the end of August, the phosphorescence would appear. We’d pick our way down to the beach in front our houses and go swimming at night. If everyone turned their lights out in the bay, and the night was particularly cloudy and dark without the interruption of the moon, the plankton swirled around our limbs. Our voices lifted and intertwined and ricocheted off the rocky cliffs and calm water. We shrieked and laughed and tried to ignore the cold. We dove and opened our eyes and forgot where we were — weightless, it was like swimming through space. We were so powerful then — we moved our fingers and woke up the stars.

How could we have grown up in a place like that and not believed in the endless possibilities that lay ahead of us?

•

It took me a while to realize how fearless we were as kids. Sam and I spent afternoons alone in the forest or else wandering through the houses near the bay that were partway through construction. We didn’t think about bears or other wild animals, about people who might not want us trespassing on their property. We’d pull ourselves up into the empty shell of homes, damp with rain and the smell of lumber, skeletal and uneasy in their uncertain path.

In the second century, Greek novelist Longos wrote about Chloe and Daphnis, who were born and left to be exposed on the side of a mountain in Greece. Discovered separately by a goat herder and a shepherd, they were unaware of each other until Eros, the God of Love, intervened. Suddenly they needed each other, but were naive because of their early exposure and sheltered existences of what they were feeling — call it love. If we were Daphnis and Chloe, or if we were four Chloes, or if we were an entire gender left out to be exposed, and if we were found separately and grew up sheltered in houses that were far from the highway that took you anywhere else, then the sudden need for each other would make sense — whether it was Eros or someone else, there was a sudden desire to seek shelter in each other. If the cure for Chloe and Daphnis was a kiss, the cure for us was holding hands in the moonlight. In it they found love; we found the possibility of each other, the bravery necessary to survive girlhood.

•

Once, Sam and I lived together in Vancouver. The house was beautiful and spacious. We built forts in the living room out of sheets and stayed up late together. We went out to restaurants and bars and took pictures of ourselves in the bathroom mirrors. We laughed until we choked on whatever we were drinking. We hung around with boys that weren’t good enough for us. We took the Skytrain downtown and wandered around the mall, trying things on but never buying anything. We applied fake nails from the drugstore and bought push up bras. We bought extra large coffees and Sam drank hers through a straw. We went for long walks around the city because we preferred that to taking the bus. We missed Audrey and Rose. We talked about our families. We made lists of all the things that we were excited for, because otherwise there was an endless listless burning in the pits of our stomachs.

Sam believed in a myriad of supernatural or magical things. When we were little, we spent our weekends trying to summon ghosts. Later, when she started getting sick, she went to see a woman who spoke to angels. She lay on a table in a room and the woman felt the energies in her body, and even though it was just the two of them in the room, Sam said she could hear footsteps pacing all around her — her angels at work.

She believed in words and the possibilities in what you could call prayer — a pleading or a reasoning or a stream of consciousness discussion whispered into a pillow or the still air of a bedroom at night. All those lists we made throughout our youth, the things we were looking forward to, what were those if not spells written for our future selves?

She made me believe in magical possibilities. For every shadow, there is first a sheet of light. I heard her up at night. I was afraid. By morning, all the kitchen cupboards were empty, their doors swung open like a ghost was trying to make its presence known. Sometimes, I found things in random places, like they’d been shoved there haphazardly when she’d heard me coming. A flashlight in the fruit basket, a knife in the freezer, a mixing bowl on the floor.

There is so much silence in pain. There is so much silence in being a girl. It’s suffocating. It is all-enveloping. I’m embarrassed at the lack of words I ever put to how Sam was suffering. Once, addiction. Another time, eating disorder. 16 years of friendship, and I can count those words on my hands.

It ended with me asking her to leave. I never wanted to be an accomplice, and at the time I saw my insistence that she leave, that she seek more professional help, as some form of tough love. But I wonder now if there’s anything more complicit than silence. Than turning your back and facing the wall, waiting for something to pass.

I dream about the bay where Sam and I grew up. In the dream, the sky is bright grey even though it’s the middle of the night. The tide is so high that it’s creeping onto the lawn, and the water’s lukewarm as I wade in. I start to swim out towards the big rock where we used to meet and dive down to the sandy bottom in search of shells and shiners. As I swim, I start getting more and more tired until I can’t keep my eyes open. I start sinking below the surface, my arms too heavy to continue their even strokes. When I open my eyes under water, I can see straight out to the rock. There’s been a shipwreck. Everything has broken into pieces — fragments of wood and furniture float, frozen, in front of me. I manage to pull myself above the surface once more but sink again and this time. When I open my eyes, the wreckage is right in front of me. A jagged piece of debris floats inches from my face. There’s nowhere else to go.

•

The summer stretches out in a haze of unemployment and smoke. North of the city, the forests are burning. Every morning on the radio, they update the reach of the blaze, but I still can’t imagine the fire existing so close. My dad spent a couple summers of his youth as a volunteer fireman, and he says that when the flames tore through the forest they sounded like a jet taking off. The sound in the city seems muffled by the smoke, though, along with the sun — it simmers neon red against a sky the color of muddy paint water.

I go to job interviews and I come home. When you finish school, everyone asks you what’s next. I tell them I’ll write, but even to me this seems like an unsatisfactory answer. I feel completely unprepared and disinterested in every job post I read, I continue wading out into the smoke of the summer, untethered by my desire to do something particular and at the same time, do nothing at all.

Is it just this city, or are people everywhere always waiting for the next best thing? An old colleague once told me that when people asked her where she worked, she always lied and said something she felt was more interesting. I hadn’t considered whether or not my day job was interesting up until that point, but after that I considered it often. When you start approaching your late 20s, you have to be extra vigilant. It’s easier to poke holes in the gentle atmosphere of expectations at that point. I wake up late and I open the curtains and the sun appears, one of those holes growing a little each day, a red stop-sign hanging comically and ominously above the city skyline.

•

I start burning sage before bed. I focus it mostly on the doorways and the electrical outlets in the house, as well as the closets and the faucets. Our apartment is home now, we’ve filled the negative space with pieces of ourselves, and we often sleep soundly through the night. In the morning, our bedroom is warm and filled with our combined exhales.

If Sam was still alive, I’d tell her that I’ve been casting spells. She would like that. She would probably know exactly what I was talking about. I’d tell her that to make a witch jar, all you need is a mason jar, some coins, some basil, some salt, some words written on a piece of paper — a prayer or a pleading or a reasoning into the ethers. I’d tell her that you combine the ingredients and then you screw the lid on the jar, and you burn a candle and you let the wax drip down and seal the luck inside the jar. I’d tell her that I keep it next to my bed, and that I shake it and I try to feel luck shining on me. There is no harm in trying.

•

Sam told me once she didn’t know what her “thing” was.

“You know what your thing is,” she said, referring to the direct path I’d taken all through school towards a couple fine arts degrees, the insistence that I’d always wanted to write. We were sitting on the back porch that we shared at the house near the university. The porch was small and looked out onto the alley behind the house. The house itself was on a quiet street that shouldered onto Pacific Spirit Park

“But it won’t pay my bills, at least not for a while,” I replied.

This didn’t lessen her distress.

I curse this city, or this country, or this time, or this world, for always insisting there is something better waiting ahead. I curse that constant rush to fill empty space, the insistence that we should avoid pain, the expectations that we are all well and thriving. I look for a spell that might bring peace. I look for a spell that will make things clear. I look for a spell that slows time.

Perhaps my nostalgia, my pining after Sam’s physical presence, is still a form of ignorance. Am I still mistaking her pain for a moveable thing? There is a moment I’m clinging to — I sit on a beach and wait for a wave to swallow me whole, and I watch her swimming out in our bay. What happens to a moment that has been left empty for so long? Who lives inside of it now?

Five months ago, Audrey called me late at night. I was awake. I held my phone in my hand and I stared at her number. I always wondered if all of our years apart lessened the connection we built as little girls, reciting homemade calls to ghosts and spells to bring about the futures of our dreams — if you say something often enough, if you hope for something wildly enough, if you direct all of your intention towards it, isn’t that a spell? All these years later, I looked at my phone, and I knew what she was going to say, so I ignored the call. I stretched out Sam’s life for one more night.

•

There is a power in the number three. If Sam was still alive, I’d tell her this, even though she already knew. It’s the number of the witching hour: three a.m. It’s the number of time — past, present, future. A door that can be opened or closed. Birth, life, death. The third time’s a charm. It’s divine. It’s sacred. Beginning, middle, end.

Come back.

Come back.

Come back.

•

I spoke to Audrey the next morning, and then I drove across town to work at the library. I forget the route I took. I turned the radio off and I drove in silence. Sam was gone, a death by suicide two days before.

I was late for work and the world rang in my ears. This was months before I celebrated a graduation, before Jonathan and I drove through town in the rain and found the slanted building, before the smoke arrived. I walked into the library and my supervisor handed me a reflective vest and told me to prepare for an earthquake drill. The library where I worked was the largest and busiest on campus, and those kinds of drills were required regularly throughout the year. Prevention instead of reaction. Preparedness.

The alarm began to sound, and I ushered students down the stairs. I closed the glass doors, and I locked them at the bottom. I carried a vest over one arm and a first aid kit over the other, and I followed the students down the stairs and out into the cold. This is just a drill, I said. The day was grey and reflected brightly off the glass walls of the library. I faced the entrance and the alarm blared steadily out. Someone once told me that if/when the big earthquake hits Vancouver, downtown will be buried in eight feet of broken glass. Imagine: trying to rebuild after that.

The first thing I’d said was: It wasn’t supposed to end like this.

•

The summer dwindles away. I find a job eventually. That’s how things go. Everything seems like it’ll be in a state of stasis forever, and then something happens anyways.

I stop putting clothes on in my sleep, and instead I wake up feeling for someone on the other side of my bed. My boyfriend works late, so I often fall asleep alone. I wake up in that same state, that midnight possession, and I’m acutely aware that I’m missing someone, that there is a negative space on the mattress next to me, but I can’t piece together where I am, when he’ll return. I feel the mattress with my hand, try to decipher whether it’s still warm from a body having just left it, or whether it’s been long cold.

•

Summer turns into early snow in November. I sit on Audrey’s porch and she offers me a blanket. She lights a cigarette for me with some effort because it was left out in the rain. Earlier in the night, she made me dinner and passed me drinks over her kitchen counter. She says she’s not ready to look at pictures of Sam.

In all the homes where I have lived, the girls of my youth took care of me for a long time. They filled the spaces we shared with possibility and with light. Even after all these years, even after all this loss, I can feel their presence from miles away. Audrey takes care of me in ways that no one else can right now. She feels the absence that I feel.

I see Sam on the street everywhere I go. A beautiful petite woman with dark hair, walking on the balls of her feet and swaying her hips, digging through an oversized purse as she goes. I pull over in traffic. I retrace my steps through a crowded mall. I hope for the impossible. I spend long moments in simultaneous hope and disbelief.

•

For every sheet of light thrown over a mountainside, an opposing side thrown into night.

•

When Sam died, I hadn’t seen her in almost two years. I’ve never been good at negotiating the boundary between being good to someone and being an accomplice to their pain. She was one of my oldest friends. I’ve never seen a person hurt so deeply. I cowered in the face of all that suffering.

When she died, I didn’t miss her physical presence — it had been so long since we’d sat out on the porch together and drank coffee or shared a cigarette, I had grown accustomed to not seeing her face. What I hadn’t realized was that I’d been counting on her life continuing on in my periphery: Even if I didn’t see her, I could feel her out there, and suddenly there was a negative space left where she used to be. I can’t say what I believe in, but I feel her everywhere.

If a boy is made of gathered things, a girl is a planet losing mass and gaining moons. She’s the milky way. She’s the atmosphere, silver and blue. She rings out like a bell across the water, and I sit in the first moment of seeing her over and over again.

•

There’s an idea that women, that little girls are soft and breakable, but this couldn’t be further from the truth. There is such a drive not to be viewed like that, not to be left behind in the dark or out in the cold that there has never been a time in my life where I wasn’t insisting that I was not afraid, to myself, to everyone around me. But perhaps when we were alone, when we were kids, the kind of toughness we sought and displayed was on our own terms. It wasn’t our parents, it wasn’t our schools, it wasn’t the world that told us where we were headed — it was a single girl’s voice asking an unwavering question through the dark, and then another responding, and then another, until together we were something undeniable. Something to really look at.

I owe them everything: my fear and my bravery. I see little girls now, whispering in groups, and pride pounds a riot in my bones. In this way, I love and fear every girl I’ve ever met.

I have a picture of us as kids. We must be 12 or 13. We’re lined up — the four of us — with our arms wrapped around each other. It’s funny how preteen girls always embrace in photos, like they understand that someone can see you and decide to turn away, like they know a secret that will make them stay.

It’s been a long time since I’ve summoned anything, but this I know to be true: I am alone but never separate. You are alone but never separate, and if people assume you are weak, or if you’ve learned to turn the dial on your own suffering or your own desire to suit the volume of the world and vaccinate yourself towards loneliness, I hope you find a path away from that soon, one that leads towards the kind of warmth you forgot you deserved. I hope that when you look at the moon or feel a ghost at the foot of your bed, the voice of every girl you’ve ever feared or loved or both will speak together, will start to cast the spell, will hold hands in the heaven of your girlhood and say clearly, voice silver against the decidedly dark sky, under the bare moon: I am alone but never separate and

GHOST GIRLS LIVE FOREVER.

GHOST GIRLS LIVE FOREVER.

GHOST GIRLS LIVE FOREVER. •

All images created by Emily Anderson.