If there’s ever been a time to dissect the experience of being a girl, it’s now: there’s girl math and girl dinner, “I’m literally just a girl” is a viral meme, pink bow emojis are rampant, you can dress like a ballerina and no one bats an eye, and No Doubt’s ’90s anthem “Just a Girl” is background noise for reels and Tiktoks.

Rewind four decades, and it’s easy to see the work of the late artist Francesca Woodman, who died at the age of 22 in 1981, fitting into this discourse. To think about her black-and-white photography — in which she often appears naked — is to consider the subject of girlhood and this metamorphosis from girl to woman that transcends generations. Woodman is having another renaissance right now — a solo show at Gagosian Gallery in New York, and a joint show with 19th-century artist Julia Margaret Cameron at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

I have a small reproduction of a Woodman photograph in my apartment: A young woman in a vintage white dress stands against a wall, palms covering her face. On more than one occasion, someone has casually asked, “Is that you?” It’s not because I resemble Woodman (I’m brunette, she was a dark blonde), but it’s because within her photographs lies something so universal to girlhood — I don’t mean childhood, but rather the act of morphing from teenager to young woman, or, as the artist Justine Kurland so astutely stated at a talk to fête the release of Woodman’s The Artist’s Books at Rizzoli last summer, “dealing with a body for the first time.”

That phrasing stuck with me because in Woodman’s photos, there is the tear between absence and presence — that is, between wanting to be fully seen but also wanting to pull away. At the Gagosian on a recent rainy Saturday, raindrops rattled the roof while I observed dozens of black-and-white photographs (from the years 1975 to 1980) in two rooms. In an earlier untitled photo, Woodman stands in her Mary Janes and an old vintage dress, face to the camera and wholly present, a bit stylized in her pose. She used the magic of a long shutter speed and double exposures to not only feature in her own photographs but also to capture movement. It was a risk: She never knew what she was going to get, but I suppose that was part of the fun. In another photo, taken the same year, that same wholly formed girl is now crouched on the floor, seemingly morphing into a vapor that appears to escape into the wall.

This theme of absence and presence pervades her work — and the desire to appear and disappear on a whim feels not only like attributes of girlhood but in some cases a necessity of girlhood (who hasn’t needed to run from danger? One only needs to think of young women being randomly punched on the street near Union Square last month). The writer Deborah Levy has echoed this on the Great Women Artists Podcast with Katy Hessel, saying, “It is so very hard, I believe, for women to make themselves present. Because there’s so much to absent ourselves from. Especially for Francesca Woodman’s generation. So, the societal gaze, or you could say, the patriarchal gaze, whatever, is so violent, that it’s on you all the time. So why would you just be totally present to it?”

The Gagosian photographs each stand alone but also flow beautifully together, like a little film playing out a non-chronological sequence. Woodman crouches naked toward a mirror with a beast-like curiosity; in another photo, she faces the camera but hides her face with the mirror so we see only her naked body. In yet another, she’s the ghost in the corner of the room—that is, a body covered in a clear plastic tarp, blurring into the opaqueness.

“What is meant to be at the centre of attention is, at the same time, liminal,” Chris Townsend wrote in the 2016 Phaidon book on Woodman’s art. “It is always haunting the boundaries, edging out of or coming into the frame, almost slipping through the surface of representation, away from us, towards us, coming out of the back of the picture, blending into the walls like a maladroit tyro ghost.”

But it’s exactly this in-between world that feels like the bridge between girlhood and adulthood and figuring out how to traverse from one world to the next. The artist Moyra Davey, speaking at the launch of The Artist’s Books last year, first saw Woodman’s photography when she moved to New York in the late ’80s. She was 30 years old and was “completely riveted and Fascinated.”

Part of the intrigue came from the fact that the style wasn’t necessarily in vogue — Woodman was ahead of her time in that sense, and her vulnerability was striking. “Suddenly here’s this young woman who’s putting herself, her body, in the photographs . . . this was taboo at the time, you weren’t supposed to do it,” Davey said. “There were all these writers and theorists who were agitating against those kinds of images in photography and film.”

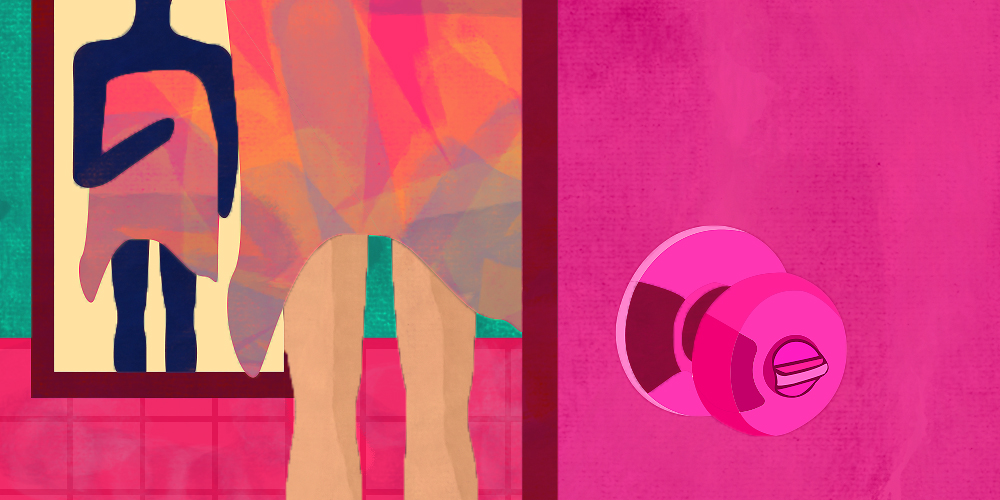

The pièce de résistance at the Gagosian show is a floor-to-ceiling diazotype temple with four women (either Woodman or her models) as the caryatids holding up the pediment, which is composed of a Greek key pattern. A little legend to the right in Woodman’s handwriting explains what inspired the temple — the bathrooms she saw living in New York City — and includes tiny photographs or illustrations of her inspiration: a sink drawing with a Doric-esque pedestal (W 103rd St), a claw-foot bathtub photo and illustration (E 12th St), a toilet on Greek key tiles (Avenue B).

The piece transforms the everyday into the mythical — but I couldn’t help but think of it within the context of girlhood. Because bathrooms are our first temples, where all kinds of secrets are kept, and blood shed and rituals performed. I drifted back to middle school — the smell of bathwater, strawberry shampoo, and the metallic taint of blood. The way you took a razor to your legs for the first time, eager to erase all that hair and transform into someone else.

“For me, if I was like 19 or 20 when I saw her work, it’s coming out of a time when I’m sexual for the first time, living on my own for the first time, dealing with a body for the first time,” said Kurland, whose teacher at the School of Visual Arts first introduced her to Woodman. She added later, “So when I saw those pictures, I was like, ‘Oh yeah, I am Francesca Woodman.’”

Art is, if anything, subjective, but nevertheless, Woodman’s work will always speak to that universal experience of girlhood and all the agonizing, painstaking, brilliant, and sparkling tragedies that accompany it — not to mention what it is to have a female body, and how we continue to appear, disappear, blur, hide, and repeat as needed. Woodman died too young — as Levy puts it, she is “frozen at 22” — but had she gone on to create more work, these early images would still speak to me about girlhood and our ambivalence about our bodies as women.

There are parallels for it in our culture right now, though decidedly less high-brow ones. Chronically online girls with overactive Instagram accounts have nothing in common with Woodman’s keen craft or refinery — but they do also make choices about their bodies and what to reveal in the squares on their grid. Comparatively, thirst traps and soft launches are ways of appearing and blurring, both debuting your presence and then fading into a mystery. (Perhaps the greatest, and wisest, example of disappearance itself is deleting one’s account permanently.) I sometimes wonder what Woodman would have made of it all — would she have relished it and seen it as another means of expression and experimentation, or would she have resented it as I do? Having social media, after all, is literally a “presence” — an expected one, at that. And the last thing most girls want is to be told that our presence is mandatory.•