When I was seven, I moved out of the room I shared with my older brother and into my own room. I don’t recall what caused my parents to decide this — perhaps it was a birthday present for my brother turning ten — but for me it was nothing if not a mixed blessing. I mean, I loved getting my own desk and new wallpaper that I picked out and my own bed, all the trappings of a room to grow up in. But without my brother there with me, there was something truly terrifying about being alone at night in the dark.

Not that my brother was much of a protector. More often he’d attack me in my sleep, steal and break my toys, and “dead-arm” me over and over again for his sadistic pleasure. But in my room alone, all alone, I felt susceptible to all the forces of darkness — the monsters under the bed, the prowlers lurking at the window, the creepers in the closet waiting to kidnap me. I had no protection at all. Leaving the safety in numbers of my brother’s room and the comfort of our New York Giants’ helmet night light filled me with imaginings of untold peril.

That October, I moved into my new room and was forced to deal with the horrors of a lifetime, of dark and scary nights all by myself. During this time, my parents found me in all sorts of strange positions in the mornings, occasionally sleeping normally, prone in my bed. But at other times, a variety of irrational phobias had me scattered in little nooks and crannies around the room. Some nights, it was the fear of people coming in through the windows that freaked me out. I hid under my bed, eventually falling asleep curled up under the safety of my great-grandfather’s old mattress and box spring that sagged so much I had to sleep on my side or else my nose would be crunched against the floor. Other nights, I thought of the possibility of murderers from the penitentiary over by the highway coming in the window (despite the fact that it was a medium-security prison that was more likely to house a tax evader than a serial killer). On those nights, I crept inch-by-inch toward the closet until I reached it and threw the door open, pushed the shoes and hangers to the side, and crouched down on the floor to sleep for the rest of the night. I still remember trying to explain to my mother how I got the vine marks on my face from sleeping against an old Frye boot with an embossed pattern.

But I wasn’t the only one in my suburban New Jersey town who suffered from irrational fears that year. That fall, the mayor and his small-town suburban flunkies had reverted back to the days of witch burning, prohibition, and Joe McCarthy; they’d cancelled Halloween. No trick-or-treating. No candy. No Halloween float contest. The whole thing, they said, was cancelled on account of the dangers faced by “our children.”

As I learned later in life, many kinds of craziness are waged on behalf of “our children.” most frequently incited by hysterics and fear mongers. In my hometown, it was no different. The local evening news reported scares of razor blades hidden in Hershey bars and pinholes stuck into Starbursts and filled with arsenic. Parents were warned about tampered-with fruit and homemade treats and unwrapped candy containing things like razor blades or shards of glass meant to harm and kill kids. No Chunky, Mary Jane, or Tootsie Roll was safe from the forces of evil plotting to harm children lured into danger by their desire to eat sweet treats.

The religious groups in town got behind the hysteria, too. The Hebrew school teachers told kids that Halloween actually celebrated the anniversary of Crystal Night, an early attack on a Jewish neighborhood in which a horde of Nazis broke windows in Jewish businesses and homes. “You go out, you are spitting on your heritage,” Mrs. Chenitz, my octogenarian teacher, warned while brandishing a long wooden stick for emphasis. “And the candy isn’t kosher, either.” The Churches in town preached against the pagan qualities of Halloween and its celebration of Satan, witchcraft, and evil. One church even promoted a “bible costume party” as an alternative to Halloween, though it was canceled when only a handful of the most pathetic kids signed up for it — the repressed gay drama kids and this girl with cerebral palsy who chased after the youth pastor with unabashed sexual aggression.

This combo of fear and guilt about Halloween had a powerful effect and caused the most insane questions to arise around even the most tried and true traditions. No one bought a costume; was that really a 666 etched into the fake stitches on that monster mask? Teachers canceled school parades; are we encouraging Satan worship with our ritualistic “best costume” contest where only one kid is left standing on stage while the other descended into the fiery shame of their seats? Candy shelves at the supermarkets remained eerily full; aren’t the ridges on the Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups perfect for coating with PCP?

As a result, the town canceled trick-or-treating all together. Instead, they would hold a parade down Main Street from Town Hall to the Library and then have the policemen and firemen hand out “safe candy,” some strange euphemistic term they used for candy the town authorities would x-ray before handing out on a measly scale of five pieces per child. That’s right — five pieces per child. To us kids, the five pieces rule was the last straw. This meant war!

For a few years, I got sick each Halloween, and the year they canceled Halloween was the first in a series of four when my own bad luck and my bacteria-ridden friends caused me to miss the Halloween fun anyway. I usually got strep throat: that routine childhood sickness characterized by little white dots that appear deep inside your throat, which you can only see if you press your tongue down, say “ah,” and stick a flashlight down there. My mother, accustomed to these sorts of illnesses from when my brother got them years before, propped a bunch of pillows on the sofa in the den, made some toast, and went off to work, confident that I wouldn’t do anything bad in her absence despite the fact that it was Halloween. She had that kind of faith in me as a child. I was, after all, the second child, the one who didn’t explode potatoes in the microwave, throw baseballs through the school’s window, or get on the wrong subway and wind up in Queens instead of heading Midtown when we went to see Cats.

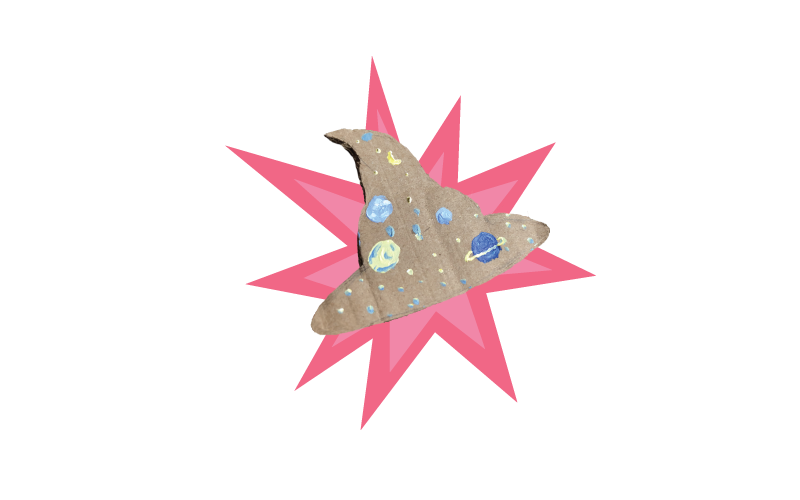

The last Halloween I was healthy for, my mother had made costumes for my brother and me out of patterns she bought at the fabric store. She was not ordinarily a crafty kind of mom, and later she would become quite the opposite, preferring to eat out at every occasion rather than cook and have her eyebrows plucked by someone else instead of doing it herself in the small theater mirror she kept on her make-up table. But that year, she had spread the patterns out on the kitchen table, revved up her dusty sewing machine, and gotten to work on our costumes in early September. My father, initially supportive of her sewing, would later encourage her to spend instead of mend. “Why do you gotta spend all your time making clothes? What are you, a pioneer woman?” But that year, she made our costumes for us — my brother’s was a clown with red and white pompoms and a droopy collar, and mine was a wizard with a black robe and a cardboard hat she’d painted planets on. If that wasn’t enough to give one strep throat, I don’t know what would.

The homemade costumes looked idiotic, and we both protested vociferously about not being able to go to a store to buy a polyester Darth Vader or a Smurf or something, anything that included masks to hide our faces. In addition to the paper hat, she also made me carry a stupid wand and wear a stringy and extremely itchy little beard that she glued on my chin with some sort of rubber cement that gave me the feeling that spiders were crawling up my face. I’m not sure the beard made it out the door the morning of Halloween, because I couldn’t stand the feeling the dried goo gave me. “Just ignore it. You’ll get used to it.” She, a great believer in self-determination, thought the mind could overcome any amount of itchiness. I remembered those same lines when I got poison ivy walking the dog through the woods and then again when I got chicken pox. Itchiness, apparently, like any mean kids at school that try to beat the shit out of you, could just be ignored.

“It’s adorable, and you can wear it every year,” she’d said with a sort of triumphant resignation of someone who, in all actuality, probably never wanted to make another costume as long as she lived, and knew that she’d just bought herself a good five years free of costume worries. From the moment she put the wizard outfit on me, I knew I’d be appearing in it for as long as it fit me, and then would, lucky for me, be tromping around in my brother’s clown thing for years after that.

It wasn’t the lame costume that made me sick the year they cancelled Halloween, though I’m not sure what did. I always thought I was just cursed, and my mother’s annual harping about my “bad luck on Halloween” didn’t make things any better. The Halloween curse that brought the streptococcus virus into my throat must have had something to do with the demons lurking in my new room at night, or so I thought. It must have been punishment for something I’d done — smashing a baking pan of my mother’s, ripping a new pair of pants at recess, telling my fat aunt to shut up — but I didn’t know the root cause for sure. The timing, like the hysteria over the sabotaged candy, could not have been any worse for a kid who just wanted to go out with everybody else and get an obscene amount of candy from the neighbors.

In retaliation for the canceling of Halloween, the kids in town understandably went nuts. No Halloween? It was like ordering a puppy genocide or instituting a Dr. Seuss book-burning. It infringed on our rights as Americans, damn it, and we were pissed! Halloween was the only holiday of the year that was ours, when we could just have fun without having annoying relatives come into town and sleep on our fold-out sofa beds, when we wouldn’t have to spend hours in church bored to tears waiting for that final “peace be with you” to put us out of our misery, or when we didn’t have to drive all the way to Grandma’s to eat her deadly pot roast and gummy ambrosia salad.

Signs written in kid scrawl began to appear in windows saying things like “Bring back Jack,” with pictures of jack-o-lanterns, or “The mayor’s a Hallow-weenie” or other such un-clever slogans. Some high school kids egged the window of the mayor’s office and smashed pumpkins on nearly every street. The tree on the lawn in front of my elementary school was toilet papered, the rolls hanging ominously like they’d be used later for lighting on fire. No stuffed scarecrow or cardboard tombstones was safe from the indiscriminate vandals who felt their holiday had been snatched out from under them like an innocent lamb by a starving wolf.

But by the time the actual holiday rolled around, any remaining enthusiasm for it among parents or kids had waned completely. So much so that many parents, exhausted by the endless whining and irritating dinner arguments, had decided to just cut their losses, throw caution to the wind, and go to a friend’s house in a town nearby or to relatives instead of participating in the squeaky-clean, sugar-coated but sugar-free Halloween.

But I missed school that day anyway, and as a result didn’t get to hear that the holiday was cancelled, didn’t hear about the canceling of the school costume parade. I didn’t hear that my friend Dave was going to his cousins and that my friend Brant was going to his Dad’s house in Morristown to trick or treat. So, left alone all day with unlimited supplies of Seven-Up and popsicles during this community panic attack, I did what any normal suburban kid would have done. I took the bag of Halloween candy that my mother had purchased weeks before all of the hullabaloo, tore it open, and spread each little 100 Grand bar and Kit Kat on the table. Grabbing a ballpoint pen, I methodically punched holes in each little candy. The first few times, I broke the wrapper and I had to throw the candy away (the pain in my throat prevented me from the obvious and readily available pleasure of eating as much chocolate as I wanted, another consequence of getting sick). But after a couple of trial runs, I mastered the dexterity needed to gently press on the red wrapper, keeping my arm still from any jarring or shaking motion when pen met candy. I left a few little blue holes on each one, just suspicious enough to look as if some evil kid killer had sabotaged this batch of candy just before my mother brought it home from ShopRite.

In a way, I was getting my revenge on the cursed Halloween gods who’d gotten me sick with strep throat. The town thought there were child predators out there trying to poison kids? I’d give them poisoned candy. They wanted a reason to keep all the other kids home from trick-or-treating? I’d give them a whole lot of reasons poked into their precious sweets. In a sense, I had become that psychopathic serial killer, just without doing anything really dangerous. I wasn’t using poison, wasn’t coring apples with razor blades, but I was pretending to, and wasn’t that just as bad?

After putting pen holes in the candy, I dropped them all into the big wooden bowl my mother set out by our front door each year for trick or treaters, and I waited. I remember distinctly putting a kitchen chair in the entryway where the candy was set up, just so I would be right there when the kids came knocking on the door. Then, they’d take the candy home thinking they’d scored a handful from the house with the sick kid, and then, hopefully, when their parents inspected it, they’d find the candy contaminated with pen holes, and panic, scream bloody murder, call the police, and run howling into the streets.

But, consistent with my Halloween luck, my mother came home on an early bus that day to check on me. She walked in the front door and found me asleep in the chair, a melted Popsicle on the table with the bowl of candy, and orange drool running down my face.

“What are you doing here?” My mother asked, waking me up as she slammed the door behind her.

“I’m waiting for the trick-or-treaters.” I sat up abruptly in my chair and pulled the blanket I wore up around my shoulders.

“Didn’t you hear? No one’s trick-or-treating this year, honey. It’s canceled.” And with that she grabbed the bowl and took it into the kitchen, where she promptly emptied it in the garbage can, my hours of devious hard work vanishing with one flick of the wrist. Without skipping a beat, she put water on to boil and started cleaning up the empty wrappers, sticks, and Dixie cups of soda I’d left around the kitchen.

“Canceled?” I called after her.

“Yep. Canceled. No Halloween til next year. Maybe.” She replied in a perfunctory way and set about reading the day’s mail. Sullen, my plan foiled, I made my way into the den and turned the television on. Tuning out to back-to-back episodes of Diff’rent Strokes was really the only way to recover from my botched experiment in evil.

Apparently it was true; my town was not the kind of place where safety was taken lightly. While we didn’t experience murders or have celebrity suicides, even petty pranksters like myself were shit out of luck that year. I didn’t have parents who spied on the commies or flew airplanes or any other risky lines of work. My suburban existence consisted of small, simple everyday things like walking home from school and selling hot chocolate on the corner on a snow day or riding my bike up to the post office to get stamps. Sometimes, though, the powers that be, like the mind of a child left alone in his new room, imagine things are much worse than they really are; that the dangers of the urban life would somehow drift over to the sleepy suburbs. That year, our town decided that fun wasn’t fun anymore. It was just plain scary.

When I watched television on the lumpy couch in the den while listening to my father on the phone telling me over and over again to drink fluids, I didn’t have that left-out feeling anymore. None of the other kids were getting Halloween that year, either. They were all stuck somewhere too, probably on their lumpy couches in their dens, watching the same reruns that I was, complaining about how unfair everything was and how godawful it was to live there. For me, spending the best holiday for kids this side of Christmas cooped up at home while everyone else was too provided me a little relief, a bit of secret satisfaction, knowing that for once, I was in the same boat with everybody else. Better than spreading hysteria in the streets, there was comfort in knowing that, at least for this year, we all had to miss Halloween.

When my brother came home with his friend and devoured pocket pizzas that would have seemed like swallowing a Duraflame log for me and bitched about the end of Halloween and the lameness of our town, I went upstairs to my new room and got into bed. For the first time, I looked around at my books on the bookcase, my poster of Superman on the wall, and I felt comfortable. No monsters of any kind — real kid killer or imaginary cartoon characters or kids in masks — would be coming to our house that Halloween. I slept a long time before it got dark and my mother put mac and cheese in a blender for my dinner, knowing that for once that I had nothing to fear. •

All images created by Emily Anderson.