I imagine a rhinoceros.

A gray hulk standing in the South African savannah, with a massive, brooding head and wary eyes, the horn a perfect mathematical curve sharp enough to slice the wind, one of nature’s great achievements. I can’t hold the image for long because it is soon replaced by another rhino in Kenya surrounded by four men with AK47s. They are the last hope to save this rhino from being murdered for its horn, a commodity worth more than gold.

I try again. This time I see a rhino on its side, a bullet wound in its neck with a trickle of blood, its face hacked off and horn missing. I let that image go as soon as I can.

Long have I wanted to see a rhino in the wild and when I joined a conservation project at a private reserve in Greater Kruger National Park, South Africa, I dreaded that my first experience with rhinos in the wild might be to see a dead one.

For ten years, South Africa has suffered a poaching crisis. In 2006 and 2007, one or two rhinos were poached per month, but between 2013 and 2017, the numbers ballooned to more than 1,000 rhinos poached each year, an average of three per day, while in 2018, there was a slight drop and 769 rhinos were poached. After losing a quarter of its population in five years, it’s possible the downturn was because there were fewer rhinos to poach. For perspective, if the USA were to lose 25 percent of its population, it would be like clearing people out of Texas, Florida, New York, and Pennsylvania. Altogether, it is less a poaching crisis and more a plundering, a systematic destruction of the population.

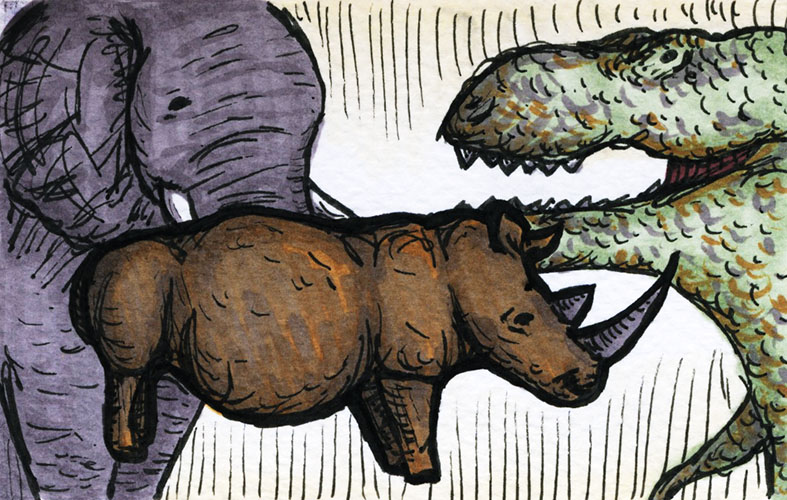

In my rhino imaginings, rarely can I get past the carnage to see the majesty that I seek, a beast as suited to walking with dinosaurs as with elephants. I remember the Borges story, Dreamtigers in which the author tries to dream a tiger, but, he says, “Never can my dreams engender the wild beast I long for.” The tiger would eventually appear, but often as flimsy, the wrong size or shape, a poor replica. I don’t know what quality the rhino has: stoic brutishness, a sort of tragic innocence, some mystique I can’t put my finger on, all of which compels me to try to see it before it is gone forever.

As a volunteer, one of my first tasks was to visit two local schools and help out with their environmental education program, known as the Bush Babies, run by a 27-year-old, always smiling woman named Lewyn Maefala. With two other volunteers, we read a story aloud to the seventh-grade class about a rhino calf who woke up in a sanctuary. She slowly remembered that poachers killed her mother and cut both their horns off with an ax. During the reading quiz, I watched 30 heads go down and hands scribble as Lewyn read out questions about rhinos, rangers, poachers, and orphanages. Though they lived on the edge of the reserve, most of the children, if not all, had yet to see their first rhino. For them, the rhino was very much an imagined animal.

When Lewyn handed back the previous week’s homework, she cheered the students who did well. If they continued to succeed in the program, they got a chance to visit the reserve. She told us later that she also paid attention to students who underperformed, to reduce the chance that they one day became poachers.

This was the topic around the campfire almost every night — how to stay ahead of the poachers? The night I arrived, Craig Spencer, the warden of the reserve, was holding court. Bare-chested, wearing camouflage pants and smoking a pipe, he asked, “Why is it that our technologies can tell us where to park in London or Johannesburg or any big city but the same tools aren’t being developed for wildlife protection?” To that end, the reserve was collaborating with an IT startup to develop a sensor that, when implanted in a rhino, could record its heart rate and communicate the data via radio to a receiver. An elevated heart rate would indicate alarm — a poaching threat. A second sensor implanted in the horn could be helpful in tracking it in the event of the rhino being poached.

I imagine a rhino poacher, perhaps 30-years-old, under-educated and unemployed, tracking a rhinoceros in Kruger. He has been offered more money than he can make in a year for a rhino horn. He doesn’t think of himself as a pawn of a large crime syndicate — if he is shot they will simply recruit someone else — he thinks instead about the money, a temporary, lucrative job to support his family. It is a calculated risk. If he is arrested, his chance of going to trial is slim. After all, he thinks, there are more serious crimes, and the rhino is just an animal. Near the entrance to Kruger, a sightings board has markers for where visitors saw elephants, lions, buffalo, leopards, cheetahs, and wild dogs, but no rhino sightings are logged as a precaution against poachers like him using the information.

While at the camp, a news report circulated about a poacher in Kruger who was killed by elephants, then eaten by lions. In fact, “Poacher Killed by Elephant then Eaten by Lions” was the headline, as if it was trying to convey some sort of karmic retribution — the animals teaming up and fighting back against their aggressors. His companions told his family what happened and they requested help from the rangers to recover the remains of the body. Another widow, another broken family thanks to the allure of poaching.

I imagine a conversation half a world away, in Vietnam, among the elite.

Hey, I’ve got some rhino horn —

Great, let’s get drunk and not worry about a hangover.

Rhino horn ground into a powder and used as a tonic. Or horns given as gifts to superiors for favors or to improve status. Horns used in the belief of curing cancer. In China, rhino horn has been used in traditional medicine for centuries to potentially reduce fevers and treat rheumatism and gout and as a sort of cure-all. Tests show rhino horn, similar to a horse’s hoof, has no medicinal value, but cultural myths die hard. Despite ads by celebrities like Jackie Chan, former NBA star Yao Ming, and Vietnamese martial arts actor Johnny Nguyen, with weak law enforcement, campaigns to reduce demand have so far had little effect.

The rhino has long been misunderstood. In Europe, most people had never seen a rhinoceros until Albrecht Durer circulated prints from his famous woodcut in 1515. Durer based his work on a description and sketch of a rhino that came to Lisbon — he never saw it. Though it was credible in terms of size and form, it was as much a battering ram as an animal. Durer showed the body as a mosaic of plates of armor, riveted together and added an extra horn between the shoulders. Yet for more than 200 years, this was how Europeans imagined rhinos. But the real tragedy is the rhino’s association with the fabled unicorn, whose horn was thought to be able to detect poisons and have healing powers. In Vietnam and China, this association has had remarkable and unfortunate staying power.

One night around the campfire, Craig said, “If one percent of the Chinese population still wants rhino horn or even one percent of one percent, rhinos are fucked.”

I imagine rhino horns in a display case, waiting for a buyer. The horns range in size from short, stubby mounds to long, curved rapiers. Despite the international ban on rhino horn trade, an economic surge in Asia has created demand among the nouveau riche. A population of Javan rhinoceros lived in Vietnam until it was poached to extinction in 2010.

How to protect the rhinos from this increased demand? Craig’s answer is to recruit and train predominantly women from villages surrounding the park to act as security guards. It’s both community engagement and economic outreach: they got a job and status within their community. The goal is to foster pride for the wildlife among the locals, even if they had not visited the reserve. If the mothers, aunts, and grandmothers of the village are excited about the wildlife, perhaps their kids will be too. They are known as the Black Mambas Anti-poaching Unit, named for the deadly African snake, and they also run the Bush Babies program. When two of them, Felicia Mogakane and Colin Mathebula, came up to dinner at the camp wearing their camouflage uniforms, I asked them the hardest part of their work. “It is not hard,” Felicia replied, “you just have to focus.” They are both proud of being a Mamba. The best part, they said, was going back to their villages in their uniforms and seeing the respect they got from children and adults alike.

A few days later, after their dawn patrol of the fence, the Black Mambas reported finding a snare on a rhino. Whoever set the snare was probably looking for smaller game — bush meat — but the snare could injure any animal, small or large. So six of us went out to search the area. We stretched out in a line an arms-length apart and walked through the bush, trying to find a thin length of wire among the grass. It seemed an impossible task. As the sun beat down I tried to avoid the thorn bushes and stay focused, as Felicia had said. How does a poacher think? I wondered. He has to think like an animal who would find pathways among the trees instead of exposing itself in the open. When the Black Mambas started in 2013, they found eighty snares per day; now they find just five or six per week. Today we came up empty.

One night, I joined the Black Mambas on their patrol of the electrified fence that forms the westernmost edge of Greater Kruger National Park. Greater Kruger is a mix of national and private reserves that’s as large as the 30 largest US National Parks combined, so once a poacher is inside the park, it would be easy to temporarily escape detection in the bush. The patrol was the same any night: they looked for holes in or under the fence, made sure the electricity is intact, searched for footprints near large trees (which could be climbed), reported vehicles parked on the other side of the fence. In the darkness, the rover’s headlights provided a feeble view, so they scanned both the fence side and bush side of the road with spotlights. We drove to the power box to make sure it wasn’t tampered with. An elephant trumpeted at our close passage and one of the Mambas promptly nicknamed him “Boogalu.” They all laughed at the surprise encounter. At the end of the fence, we stopped for an “Observation Post.” The rover’s engine was turned off and we listened for anything suspicious: voices, gunshots. I strained to hear anything beyond the buzz of power lines. A baboon barked. The Milky Way blazed overhead. Tonight, there was nothing to report.

Why do we look at animals? There could be 100 answers to this, all equally valid. To experience an otherness, a mystery in the living world. To glean the secrets that make them so similar and different from us. Because they are strange and beautiful. Because we envy their qualities of strength or fleetness or dexterity. Because we love their unabashed wildness and long for that in ourselves. Though we’ve had a century and a half of Darwinian evolution, where humans occupy one branch on the Tree of Life and rhinos, elephants, giraffes, and lions all occupy other branches, we still harbor the 19th-century notion of the Chain of Being, that humans are the top rung on the ladder and animals are on various rungs below us. In The Outermost House, Henry Beston wrote, “We patronize them for their incompleteness, for their tragic fate for having taken form so far below ourselves.” This is our folly, to see the animal as something we can use and manipulate, rather than on its own terms, in control of its own life. Beston continues, “For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours, they move finished and complete, gifted with the extension of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear.”

Around the campfire, Craig also spoke about an attitude shift that he’s hoping to engender. He called it environmental patriotism. He said that people visit France, for example, for its culture and architecture, achievements that the French are justly proud of. Even if the Nazis would have won, he argued that French culture would have persisted because of the resistance. I thought of the recent fire at Notre Dame Cathedral, how a billion euros was pledged for its restoration in just a week. Craig wanted the same for South Africa, for people from all over the world to visit and see these incredible animals, and for the locals to be proud of them. Poverty and previous apartheid laws, which prohibited blacks from entering national parks, have formerly led local people to see wildlife as “something that belonged to white people.” But between the goodwill and positive press that surrounds the Black Mambas, who are succeeding in work thought to be for men only, and the long term Bush Babies program, I imagine a local pride taking hold, and flourishing.

My timing at the reserve was auspicious because while I was there, the owners decided to take an extreme and controversial step to protect their rhinos. They were going to remove their horns. Both male and female rhinos have horns; males use them to attract mates and females use them to protect their young.

I imagine a rhinoceros, charging through the bush.

The procedure begins with a plane circling to find the animal. Once found, a helicopter chases it and darts it so that the animal falls forward onto its sternum, which reduces the risk of injury. Then the ground team has three minutes to remove the horn before complications arise.

At dawn, another volunteer and I accompanied Leonie, a field technician at the reserve with long black hair that matched her unlaced black boots, to track two of the last rhinos that had yet to be dehorned. It was a mother and her calf and though checking the camera trap turned up nothing, Leonie had a hunch where they might be and we drove to the edge of the reserve. She soon picked up the familiar three-lobed footprints on the dirt road and radioed in the information. Some fresh dung — still warm — confirmed her suspicions about the direction they were heading. A plane was called in to circle the area and we waited. I wondered if the first rhino I saw in the wild would be madly charging towards me, chased by a helicopter. But the plane kept the rhino beyond us and when the helicopter was called in, we were too far away to be involved.

We drove to the rendezvous location and waited for the other ground teams.

Suddenly, down the hill, the calf of the now-dehorned mother charged out of the bush, like a wild child throwing a temper tantrum. It crossed a road and plunged back into a protective cover. Just beyond our sight, the helicopter caught up to the calf and darted it. We gave chase but in a Keystone Kops moment, stopped suddenly when the veterinarian’s Land Rover ahead of us ran out of gas. They threw all the equipment into the back of our vehicle, we switched drivers and sped madly through the bush, careening between trees and axle-crunching boulders. Three ground teams pulled up and we each grabbed chainsaws and vet kits and ran to the downed calf. The veterinarians applied the blindfold — it looked like a big baby with a toothache. The chainsaw roared into life and the nub of the horn, no more than three inches long, was sawed off. A harsh sound for a harsh but quick operation that I could barely watch. The vet carved away the stub with a grinder and applied resin so that it looked somewhat natural. But it was still a rhino without its horn. Another vet applied the anti-sedation serum and we dashed back to our rovers. Once the calf awoke it would cry for its mother and hopefully the two would quickly find each other. At least in this case, unlike the story we read in the school, the calf’s mother was still alive.

Back at the rendezvous spot, one of the other teams produced the mother’s horn and I gasped at its size, like a crescent moon, but with a wider base. I couldn’t quite process seeing the horn without its rhino; momentarily I felt like we were in collusion with the poachers. The horn was to be handed off to a government official and kept in a bank vault. It is legal to sell rhino horn in South Africa but illegal to sell it internationally.

I imagine a rhino without its horn.

Dehorned. Defaced. Defiled. It’s like taking the roar out of the lion, the laugh from the hyena. Though I understand the logic of trying to buy time until demand goes down or less invasive — and traumatic — protections can be devised, such as microchip implants we heard about at the camp, it robs the rhino of the very thing that makes it a rhino. When I was on patrol with the Black Mambas, Goodness Mhlanga, who was driving the Land Rover, said the dehorning didn’t sit right with her, that the rhino became like a toy with the best part broken off. Though the horns grow back, I worry rhinos are being used as pawns, that private reserve owners are dehorning their rhinos as a stockpile, in case the international ban ever gets lifted.

I imagine a great pile of rhino horns going up in flames. In a high profile public burn, like Kenya has done with elephant tusks. Only burning the horns will prevent them from finding their way out of the country while the price is so high. But in 2017 owners of private rhino farms convinced South Africa to lift the ban against selling rhino horn, so burning the stockpile is unlikely anytime soon.

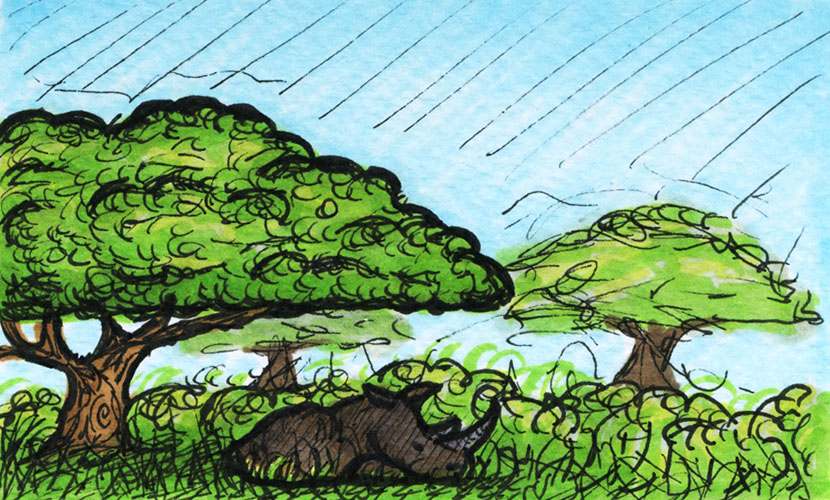

In three weeks at the reserve, the downed calf was the only rhino that I saw. I finally saw rhinos a week later in Huhluwe-Imfolozi Game Reserve (“Sha-shlu-way Im-full-oo-zi”), south of Kruger, where the white rhino was restored from the brink of extinction a century ago, and they were every bit as beautiful and mysterious as I had hoped. I first glimpsed a mother and her calf grazing in the bush, wandering away from the dirt road. Through the trees, I could barely see the mother’s horn curve upwards like a scimitar and I gasped as if I was seeing one of the secrets of life. In the afternoon, I drove back to the same place and now two rhinos stood side by side in a clearing, watching me pull up thirty feet away. I held my breath and we stared at each other for several seconds as they tried to assess whether I was dangerous. I could scarcely believe that after all this time, I was now looking eye-to-eye at not one but two rhinos, each with their horns. Then in an instant they turned with stunning agility and dashed into the bush, leaving a cloud of dust glinting in the sunlight. Later, in a wide-open savannah, I saw eight or ten rhinos — a veritable “crash” of rhinos — lounging in dried up water holes and resting in the shade of a bush or tree. They too still had their horns, for now.

The rhino in Kenya that was guarded 24 hours a day was named Sudan and he died in 2018 after months of poor health. He was the last male northern white rhino and is survived by his daughter and granddaughter. The rest of the population has been wiped out by poaching. The same could happen in South Africa.

I don’t want to imagine, a few years from now, the last few rhinoceroses in a sanctuary within the reserve, guarded around the clock, unable to be seen by the public while the poaching crisis continues. But I don’t know what I would do if we lost the rhino. What I most want to imagine is exactly what I saw in the late afternoon at Hluhluwe-Imfolozi, a crash of rhinos wandering out of the bush, unmeasured by humans, resting in the open savannah, snoozing in the shade, moving finished and complete, free. •