An old sea dog sits by a campfire, telling a dark and mysterious tale to a circle of entranced children at five minutes to midnight, aka the witching hour. We are informed that tonight is an ominous anniversary because a century ago a clipper ship called the Elizabeth Dane was engulfed in the thick fog off the bay. The sailors mistook a fire on land for salvation and ended up crashing against the rocks. The old-timer matter-of-factly explains that their souls rest uneasily under the sea, awaiting the chance to take vengeance. Then the opening credits roll as the pulsing soundtrack begins.

This is the mood set in the first scene of John Carpenter’s The Fog, a supernatural thriller equipped with some pithy insights about reckoning with history and the collective response to a mysterious catastrophe. One thing I love about Carpenter’s best films is how they serve up their social commentary. Plenty of cinephiles (myself included) go gaga when their favorite auteurs — your Kubricks, your Godards, your Malicks — act as oracles pondering Really Deep Thoughts.

At the same time, though, maybe all the cinematic philosophizing can be, well, a little ponderous. Sometimes we just want movies to be entertaining, rather than feel like an ersatz philosophy seminar. Besides, as Tori Amos once sang, what’s so amazing about really deep thoughts? The trick is to smuggle subversive ideas and insights within genuine entertainment that has mass accessibility. That’s when a film is really able to move people into fresh ways of seeing.

John Carpenter knew how to do it. All those t-shirts, skateboards, and graffiti that shout OBEY at you originate from his 1988 movie They Live, an occasionally goofy but subtly incisive satire on the social manipulations of global capital starring none other than WWF wrestler Rowdy Roddy Piper, sporting quite a majestic mullet. He finds a pair of sunglasses that unveil the sinister permeation of media, commerce, and daily discourse by alien entities.

It caught on as a cult classic for a reason, as did quite a few of Carpenter’s films. Especially 1978’s Halloween which turned a niche genre mainstream by being a massive hit and placed the stalking, impassive male psycho right in the middle of the eerily placid California suburbs, using real streets and sidewalks as the setting. Then there’s the Cold War paranoia of 1982’s The Thing, suffused with ambient dread about a weapon of mass destruction appearing within a remote Antarctic outpost.

Sandwiched between these two socially conscious thrillers, The Fog deepens Carpenter’s look into America’s murkier moral ambiguities while delivering all the frisson of a thriller. It didn’t do so hot when it was first released, but it’s gained in reputation since. It still works when seen through today’s eyes, especially given all the contemporary debate over how to think about the darker sides of American history while in the midst of a mass pandemic.

The film explores how a (mostly) unexpected ethereal menace affects the community of Antonio Bay, a small seaside town on the Northern California coast. We meet a haunted priest who uncovers an ancestor’s ancient diary that reveals the true reason for the wreck of the Elizabeth Dane all those years ago. Turns out it wasn’t just a maritime accident after all. In fact, it was a cruel decision on the part of the town’s founders, who were revolted at the prospect of a leper colony posed by the rich, afflicted Captain Blake and who deliberately sabotaged his ship in order to insulate themselves from outsiders and cash in on its golden cargo.

So the town’s centennial is cursed. Its history is bloodier than most of the locals realize. Especially not the insufferably perky Elizabeth Solly (played by the great Janet Leigh) who is fussily planning a big patriotic celebration complete with spangled bunting garlanded around the center of town. Jamie Lee Curtis (Leigh’s actual daughter) is a spunky, free-spirited hitchhiker who finds her way into town while thumbing her way up the coast. She’s the kind of person who tests her new driver by playfully asking him “are you weird?” and is pleased when he amiably replies in the affirmative. We’re meant to like the locals of Antonio Bay, and we do, which intensifies our response to the imminent threat to their safety and well-being.

Late-night DJ Stevie Wayne, played by Carpenter’s then-wife Adrienne Barbeau, is definitely the coolest character in the film. Wayne helms the graveyard shift from her lighthouse radio station poised above the bay, her suave voice fending off cheesy come-ons from callers and dedicating songs to various townspeople. In a nice touch, Stevie spins only big band jazz, which was apparently chosen just to save money on the budget. It really adds something spookily antique to the atmosphere and doesn’t overpower the luminous, ominous fog as it slowly creeps in along the horizon.

The vengeful zombies hiding within its mist — I told you this was an 80’s movie! — are mute manifestations of the lingering historical guilt embedded in an otherwise nondescript town’s secret past. Carpenter’s concern for the ways in which Antonio Bay’s submerged history returns to haunt the townspeople doesn’t overshadow their indifference, confusion, and tenacity.

It’s not all that different from real life, as it turns out, 40 years later. Some pundits declare that any discussion about the genocide of Indigenous people and/or the multi-century tradition of chattel slavery, to pick just two examples, is merely hating on America. Perhaps The Fog‘s lost crew of angry ghosts offers a potent metaphor for this debate about America’s buried past: to accurately address America’s history requires us to reckon with the unsettled ghosts that refuse to stay dead, which is another way of saying ignored.

Unpleasant as it is to consider, there’s just no getting around the fact that America was built on blood-stained land. The desire to avoid unpleasant facts is understandable in some ways. No one enjoys a peek into the skeletons in the collective closet. But even if we sometimes choose to avoid addressing them entirely at a certain point they can’t be simply brushed aside. As the priest says after reading from his grandfather’s diary account of the wreck of the Dane: “the celebration tonight is a travesty. We’re honoring murderers.”

There’s nothing wrong with patriotism, of course, as long as it’s based on a critical and clear-eyed understanding of your country’s sins. Some philosophers claim that this moral inventory can only be done after a conscious sifting through its catalog of wreckage. As Walter Benjamin once put it: “there has never been a document of culture, which is not simultaneously one of barbarism. And just as it is itself not free from barbarism, neither is it free from the process of transmission, in which it falls from one set of hands into another.”

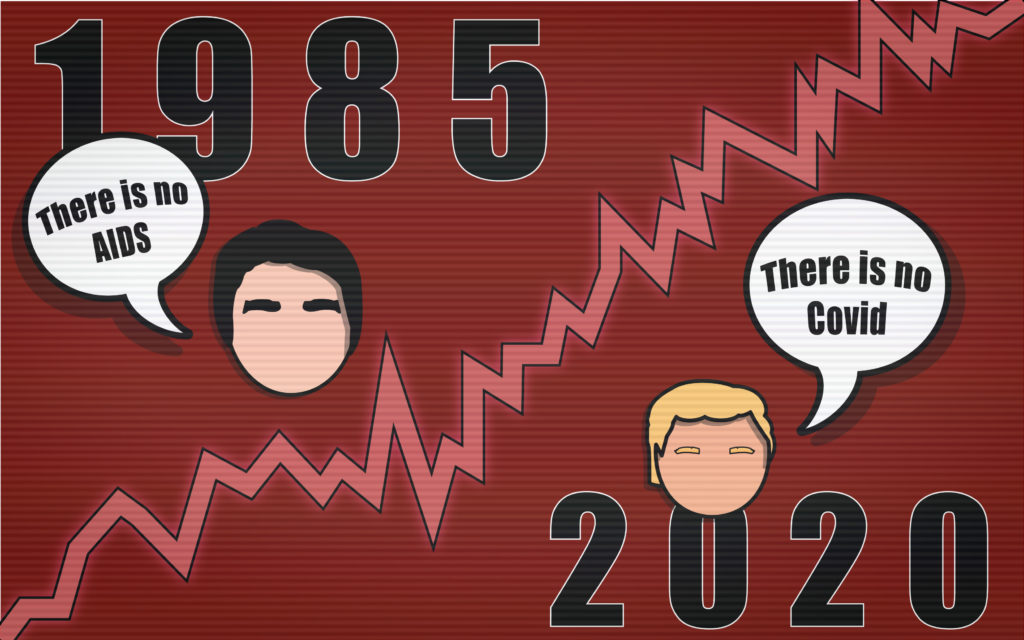

Carpenter’s ghosts first appear as poltergeists — which also happens to be the title of a contemporaneous horror film that also treats history as a supernatural return of the repressed. Moviegoers at the beginning of the Reagan years might not have been too keen on this kind of thinking: the three highest-grossing films of 1981 were Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Ark, On Golden Pond, and Superman II. Amid all the Reaganite triumphalism, there were plenty of unsettling things happening, if you cared to look. Despite the cheery “morning in America” of Reagan campaign ads, the two-term governor of California’s CIA became increasingly involved in covert action in South America that eventually morphed into unconstitutional subterfuge in the Middle East.

Famously, Reagan reframed America as “a shining city upon a hill” which was intended to promote a return to Puritan innocence and piety after all the Nixon-era scandals and the pervading malaise and disappointment. And the Puritans didn’t exactly have a clean social record themselves. AIDS was first recognized as a new disease the year that The Fog was released, another initially mysterious and deadly virus that eventually became a plague that spread throughout the decade, ravaging segments of the population, partially because of Reagan’s administration consistently ignoring it as a public issue.

The ghosts in The Fog initially intrude on the town obliquely, through randomly dripping water, spontaneously shattered windows, fragments from the wrecked ship, or a metallic hook clunking balefully against a door. These ghosts don’t announce themselves, but their presence is pretty damn unmistakable. It makes thematic sense that they are creatures of the fog, invisible and almost insubstantial yet nevertheless utterly and implicitly deadly. What you don’t know, or willfully choose to ignore, might well end up hurting you.

These days, the fog also serves as an evocative metaphor for the coronavirus, which came essentially out of nowhere and has steadily seeped into the news cycle all year, stalling much of life on this planet, especially in America. Over the past year, life occasionally feels like something out of a surreal horror film. The virus is airborne, contagious, with mysterious origins, and if you happen to contract it you could be playing Russian roulette with your own or someone else’s life.

The fog in the film is amorphous, palpable yet hard to define, which also serves as a metaphor for the confused way people treat the information on how exactly to deal with it — it’s not a stretch to say that quite a few of our fellow citizens are inhabiting their own clouds of misinformation, conspiracy, and paranoia. Ivermectin, anyone? How about a bit of hydroxychloroquine? Didn’t the last President say you can bleach it out and blithely promise that it’d be gone by last summer?

Antonio Bay’s citizens didn’t particularly do anything to deserve their haunting. Yet they tend to look out for one another during the collective threat. It’s a generous and, I think, mostly accurate way to look at how people generally — though by no means always — tend to rally together in times of collective trial. A couple who haven’t been together long bind closer to each other. Some brave souls stand up and try and fend off the encroaching darkness.

When the climax between the ghosts and the living finally occurs, there is some kind of cheesy special effects intended to be a little more impressive than they come across today, with the 80s era graphics not quite at today’s head-spinning standard. The forces of darkness duke it out with the living, and eventually, the order is restored to Antonio Bay — almost.

As the fog recedes from whence it came, DJ Stevie Wayne gets the last word by giving her audience (and, by extension, us) the sensible advice we really need to remember in a pandemic. Don’t just curse the heavens at our cosmically bad luck, or jam our collective heads in the historical sand, or pussyfoot around about whether or not we need to actually do anything to fix the problem.

As the orchestra strikes back up, and the dark sea glimmers on the horizon, the crisis is averted but we’re not out of trouble yet. Wry Stevie advises us all to look long and hard at the deep, dark, painful (but no less true) facts about ourselves and about the world we inhabit and to always remain on guard: “I don’t know what happened to Antonio Bay tonight. Something came out of the fog and tried to destroy us. In one moment, it vanished. But if this has been anything but a nightmare, and if we don’t wake up to find ourselves safe in our beds, it could come again. To the ships at sea who can hear my voice, look across the water, into the darkness. Look for the fog.” •