There are three kinds of Gerald Jablonski stories.

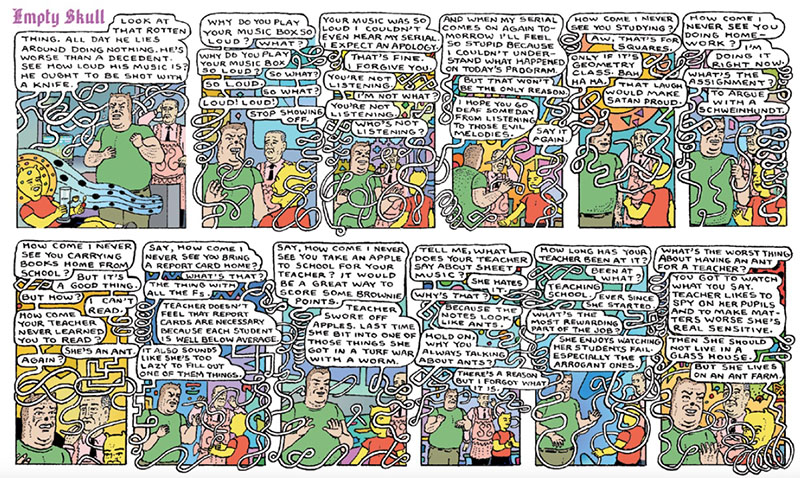

The first stars Howdy, a middle-aged, bear-faced (or is it dog-faced? It’s difficult to tell) man and his nephew, Dee Dee, a yellow-skinned lad with tiny dog ears (or are they horns?). Howdy is perennially upset because Dee Dee is playing music by his favorite band, Poopy, too loud and Howdy can’t hear his serial radio program. The pair start to bicker and trade insults. This always, always, always turns into a discussion of Dee Dee’s teacher, who is an ant. As in the insect. There is a third man, “a friend of Howdy’s nephew”, who looks a little bit like Felix Unger, wears a pink apron, and hangs in the back of every panel with a pained expression on his face. He never says anything.

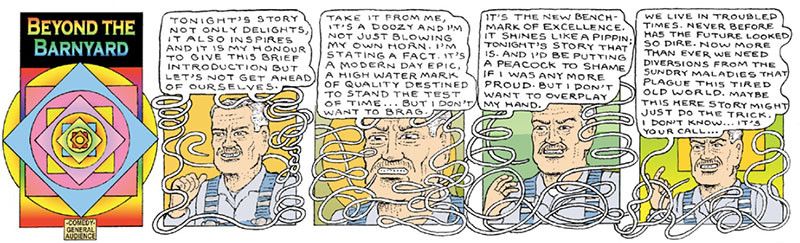

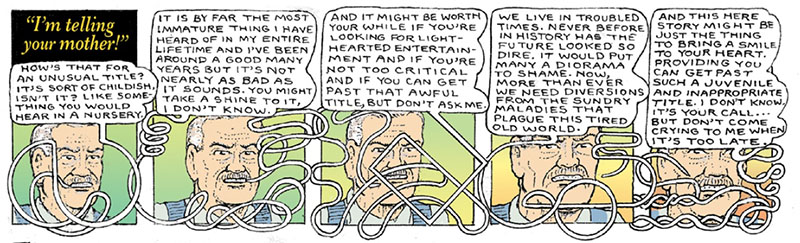

The second stars Farmer Ned, who likes to tell stories involving barnyard animals. Farmer Ned always begins his story by either lamenting the deplorable state of the world at large or greatly exaggerating the virtues of the story he’s about to tell. Sometimes he does both. His monologue can often take up more page space than the story itself. The titles rarely have anything to do with the story. (In “Miracle in the Barnyard,” Farmer Ned admits he completely made up the title to get you to read the story. “And since we’re in the last panel it seems to have worked, right,” he asks.) Ned’s tales usually involve barnyard animals of disparate generations hurling insults at each other. Often a child will berate a clueless parent. Sometimes there’s a smart aleck horse (it’s usually a horse) that’s causing trouble. Either way, lessons are rarely learned. (Jablonski’s stories don’t conclude so much as stop.)

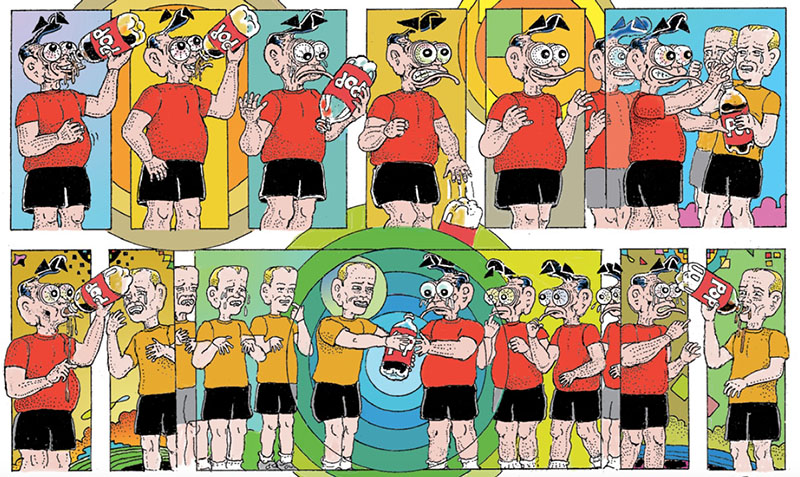

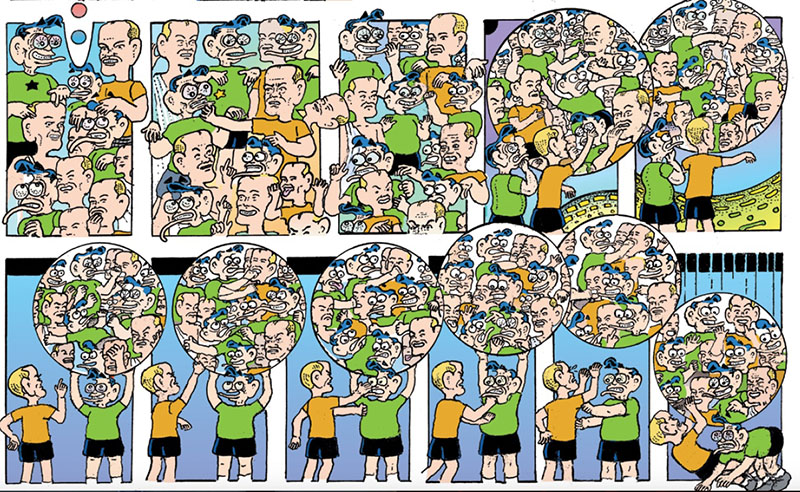

The third segment (and the most infrequent) stars two children. At least I think they’re children. One looks a little like a cross between Ronald Reagan and a chimpanzee. The other sort of resembles an angelic Gerald Ford. The former preys upon the latter in a variety of aggressive and often violent ways: snatching food and drink, destroying toys, and physically assaulting each other in various ways. Neither character ever speaks. These wordless strips usually devolve into a psychedelia of sorts, where the panels and characters overlap and break down in an odd exploration of motion and form.

These are the only types of stories Gerald Jablonski tells. Which is not to say there aren’t variations within the formula. Sometimes Howdy and Dee Dee visit Mount Howdy — a mountain that bears the face of its namesake (Dee Dee always uses this as an opportunity to throw a rock at the mountain’s face). Sometimes they take a trip to Dee Dee’s school, Spookhauser Memorial Central Academy. Sometimes the younger barnyard animals mention that they have an ant for a teacher. But even these deviations fall well within the template Jablonski has created.

There are other repeating motifs. Certain words and phrases pop up frequently: “Many things were heard that day”; “Mother, mother tell me true”; “Go ‘huh’ yourself”; “hogwash”. He has a special fondness for the German insults “schweinhund” and “dummkopf”.

Then there are the word balloon tails, those little points at the bottom of the speech bubble used to indicate who is speaking. Jablonski turns these tiny points into mile-long snakes, winding up and down the panel, twisting this way and that, forming highly elaborate patterns and shapes to the point of frequently obscuring the characters’ faces. All this while geometric patterns appear in the background. Let’s not put too fine a point on it: these are quite likely the densest strips you’ll ever attempt to read.

Very little is known about Jablonski, beyond the fact that he was born in 1953 in Rochester, N.Y, and has lived there ever since. His work first appeared in the seminal 1970s underground comics anthology Arcade (number six to be exact). He popped up in various other anthologies throughout the ensuing years, and some of that work was collected by Fantagraphics in 1996 as Empty Skull Comics. It wasn’t until 2002, though, that — with the help of a Xeric grant — he was able to self-publish the first issue of an ongoing (sorta) series, Cryptic Wit. Issues two in 2008 and three in 2012 followed via print-on-demand. Now a new, bookshelf-ready collection, Farmer Ned’s Comics Barn, has arrived that collects the content of those last two issues, along with some new material.

Reading Jablonski’s comics over time, you start to notice other themes beyond the repetitive plots and curlicue balloon tails. Both Howdy and Farmer Ned, for instance, engage in frequent and lengthy tirades about the deplorable state of the world and the “troubled times” we live in. Hints are occasionally dropped at a coming apocalypse. Suggestions are made about the general awfulness of the current generation.

In fact, Jablonski gets a lot of mileage out of mining generational differences for comedic purposes. Not just between the stuffy Howdy and impish Dee Dee, but also in the Farmer Ned tales, where doting parents are mocked as fools and sentimental softies while sterner authority figures clumsily attempt to berate smart-aleck young folk, rarely to any avail.

Given the obsessive and eccentric nature of Jablonski’s work (in the introduction to Comics Barn, fellow cartoonist Jim Woodring glowingly opines that “his comics have that alarming glass-hard veneer of isolated intellect that distinguishes the product of the bona fide lunatic”), it’s tempting to want to see these anti-youth tirades as reflective of the author’s actual beliefs or personality or perhaps hinting at some unknown personal experience or trauma.

But to do so belies Jablonski’s clear desire to entertain. The stories in Comics Barn play out in many ways in the same manner as your average TV sitcom or (perhaps more accurately) old vaudeville act, with the traditional straight man and comic foil relaying insults and punch lines along familiar themes ad nauseum. (Certainly, there is no lack of tired TV programs that drag out the tired “these kids today” saw or feature some wisecracking prepubescent.) Howdy and Dee Dee owe as much to Abbott and Costello as they do to the underground comics scene that birthed them. Listen closely and you might hear a “ba-dum-tish” or laugh track at the end of one of his panels. Certainly, his dialogue sometimes seems comes straight out of an old-fashioned “wacky riddles” book:

Goat: Who knocked over the garbage can?

Horse: Guilty as charged.

Goat: Why would you do something like that?

Horse: Because I heard that you like to talk trash.

It sounds hackneyed, but the thing that is Jablonski is frequently very funny. No really. Despite the timeworn “set-up/punchline” format and frequent use of puns, his jokes land more often than not. (Howdy: “We all made do with what we had.” Dee Dee: “That sounds unsanitary.”) Beyond the humor, though, a good part of the pleasure in reading Jablonski’s work lies in wondering what sort of spin he will put on each strip to make it apart from its myriad other seemingly identical brethren. At what point will Dee Dee start talking about his ant teacher? Will Farmer Ned make another lengthy plea to earn a Humboldt Award? When will someone call someone else a “dummkopf”? Will the story be told in reverse? It’s the minor variations, and not necessarily the melody, that make Jablonski’s comics special.

Certainly, Farmer Ned’s Comics Barn can be regarded as an acquired taste, a term that is often analogous to “stay far away from it.” I would strongly make a case for diving in nevertheless — beyond the sheer strangeness of the material, Jablonski’s comics have a transfixing charm. It’s preferable though to not try to read the entire book in one sitting (as I foolishly attempted for the purposes of this article). Rather, it’s best to stick to one or two strips a day, a daily devotional of sorts, providing adequate time for contemplation on one of the most unique and peculiar voices ever to make comics (and that’s saying something). •

Images courtesy of the publisher, Fantagraphics, and the author.