My family and I have a game that we play around the dinner table every so often, unofficially titled “Name Your Favorite Little Lulu Story.”

For my teen daughter, it’s inevitably the story where Lulu and Alvin fall into hysterics over the sound of the word “foot.” My wife prefers the one where the gang goes to the beach and a crab keeps stealing hot dogs. For me, it’s always the story where a vengeful Lulu cons the neighborhood boys into wearing diapers and then sends them careening (via wagon) down a hill into the middle of the road. My son isn’t as big a fan as the rest of us, but he does like the one where Tubby attempts a daredevil act and Alvin keeps yelling “fake.”

There aren’t many works of art, cartoonish or otherwise, that can get us all gushing like that during mealtimes, to the point where we’re acting out our favorite lines of dialogue. But those Little Lulu stories hold a special place in our home. In an age where any media that claims to have an “all-ages” appeal usually just indulges in cynical, tired jokes and simpering cliches, these decades-old comics manage to be that rare work that can inspire genuine delight in both children and adults.

The fact that a comic book series made for kids some 60-plus years ago can still be capable of engendering such cross-generational enthusiasm is largely due to the efforts of cartoonist John Stanley, who worked on the strip, along with artist Irving Tripp, from roughly 1945 to 1959.

Though he is regarded today as one of the masters of the medium, Stanley spent most of his comic book career in relative obscurity. Like virtually every other cartoonist slaving away in the funnybook business during the so-called “golden age,” Stanley produced story after story just for the paycheck and perhaps to amuse himself. It is only through the efforts of fans and scholars years later that we are able to put a name to the work.

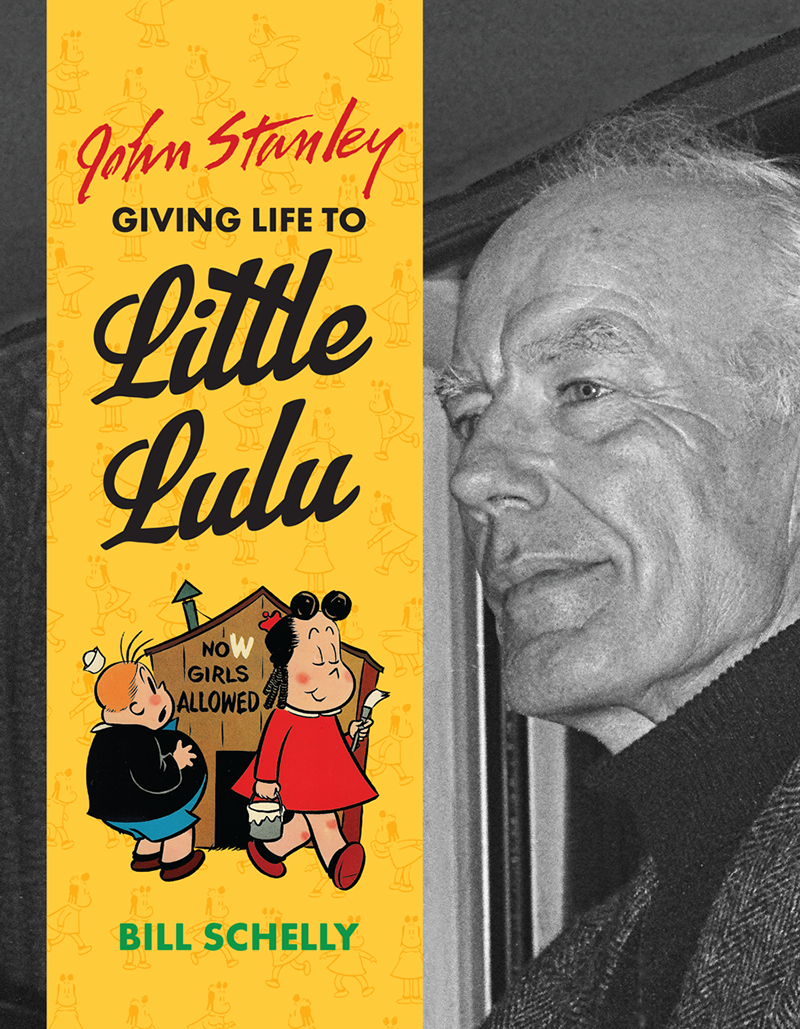

Now, 24 years after his death in 1993, Stanley has finally gotten his own biography, John Stanley: Giving Life to Little Lulu, by Bill Schelly, an oversize coffee-table book that attempts to provide some insight and background into the man who made such cherished work. Stanley, however, was a private man who didn’t provide many details about his life and work willingly, and thus, Giving Life, though it fills in some important details, can be a frustrating book at times.

Little Lulu was already a star by the time John Stanley got his hands on her. Created by Marjorie “Marge” Henderson Buell in a series of one-panel cartoons for the Saturday Evening Post, she was a smart-alecky, headstrong little girl frequently getting into or about to get into trouble. Animated cartoons featuring the character had already been produced and a advertising campaign with Kleenex catapulted her to national recognition. Assigned the task of creating a monthly comic book for Dell Comics, Stanley took Buell’s basic framework and ran with it, creating a thriving urban landscape for Lulu Moppett to play in and explore, filled with know-it-all boys in need of a comeuppance, bratty neighbor tots, would-be detectives, and even the occasional witch or ghost.

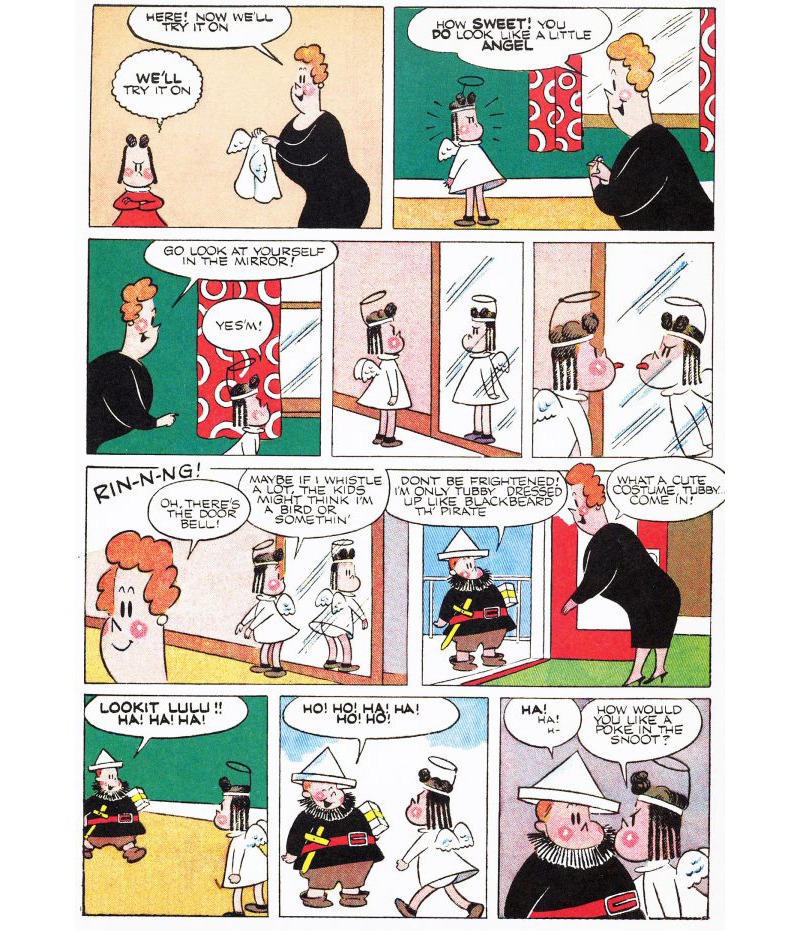

Stanley’s Lulu stories tend to fall into a few basic formulas: 1) Lulu is at first tricked or shunned by the neighborhood boys but then exacts revenge, proving her superiority; 2) an innocent Lulu tries to avoid Truant Officer Mr. McNabbem; 3) Lulu is in trouble at home and her friend, the overly confident Tubby Tompkins, decides to play detective, which always involves wearing a ridiculous disguise; 4) In order to get him to calm down, Lulu tells a story to the younger Alvin, which usually involves a nasty witch named Hazel.

Not every story in Stanley and Tripp’s lengthy run is a gem. But the true gems — and there are many — shine brilliantly. Stanley’s perhaps greatest skill in comics was his sense of pacing and timing. Adhering to a strict eight-panel grid, Stanley’s stories — ably abetted by Tripp in a style that aped Buell’s original cartoons but still managed to generate its own warmth — unspooled an at-times cynical wit that bespoke knowledge of children’s capacity for selfishness and insensitivity. It’s truly a joy to watch a tale like “Five Little Babies” (the one about the boys in diapers) methodically build towards its ridiculous climax.

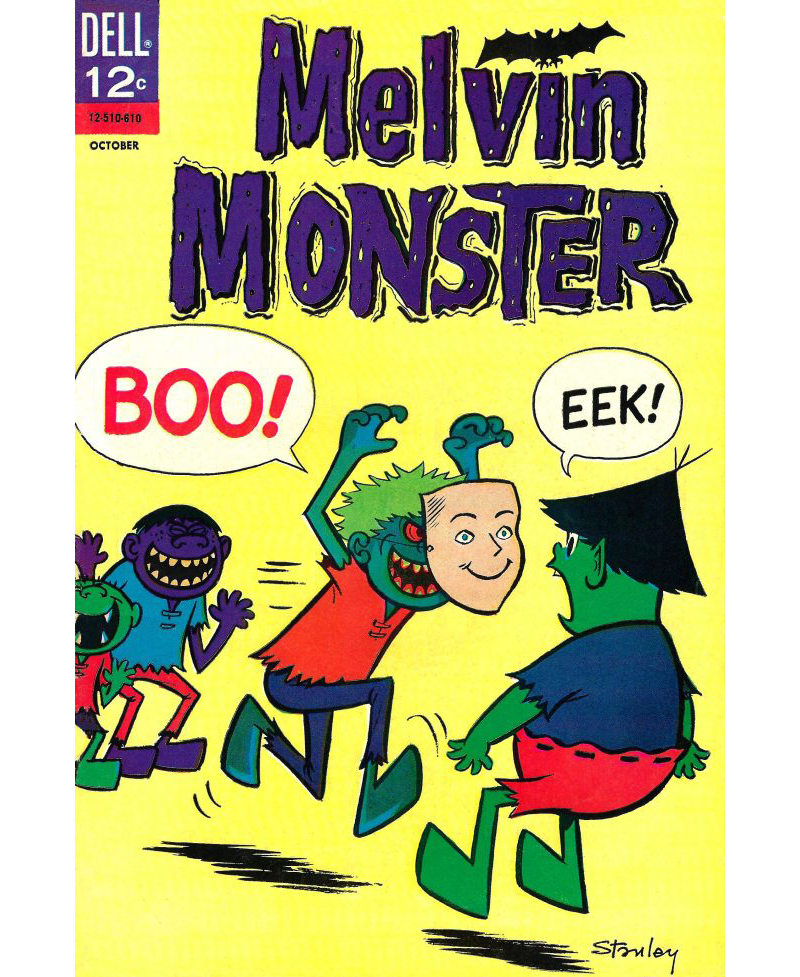

It wasn’t just on Little Lulu that Stanley shone. He also spun Tubby off into his own series and wrote stories based on Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy comic strip, Woody Woodpecker, and other licensed characters. Towards the end of his career in comics, he even got to create some of his own titles, most notably Melvin Monster and Thirteen Going on Eighteen. None of these later titles sold well, unfortunately, but they’re notable today for being drawn by Stanley (he usually only provided a detailed penciled layout that the artist would then follow). As such, they display a frenzied slapstick that’s as delightful and engaging as it is dizzying.

Read It

John Stanley: Giving Life to Little Lulu by Bill Schelly

Perhaps part of the reason why Stanley’s stories resonate so well in the 21st century (beyond the blatantly feminist message Lulu provides) is that he doesn’t shy away from the darkness. Many of his comics toy with elements of the supernatural. Ghosts and monsters make regular appearances — sometimes in dreams, sometimes not. Nancy, for example, has a neighborhood friend that comes straight out of the Addams Family. And there’s a Tubby story involving a haunted hotel that’s only a few steps away from being full-on horror (Stanley actually did a handful of horror comics that are well-regarded today but only caused angry letters from moms at the time.)

More to the point though, there’s a meanness that creeps up ever so slightly in Stanley’s work. Consider, for example, the backup Judy Junior stories in Thirteen, which focus on a young girl who is unrelentingly abusive to the smaller boy next door. Melvin Monster, meanwhile, is a likable, plucky kid, but mocked by his peers, hated by the townsfolk, menaced by his angry (but incompetent) father, and ignored by his oblivious “mummy” (whose face is literally bandaged so she can’t see what’s taking place in her home). Despite ostensibly producing comics for children, Stanley’s best work is fully cognizant of the various cruelties one encounters throughout childhood, both self-inflicted and otherwise.

Where did this darkness come from? In Giving Life, Schelly frequently mentions Stanley’s struggles with depression and alcoholism, but he’s often maddeningly vague on how those aspects of his personality and behavior manifested themselves. He quotes liberally from Stanley’s son, Jim, who talks about his moods and general demeanor, but the book sorely lacks specific anecdotes that would reveal Stanley’s demons on a more intimate level.

A good deal of that is not Schelly’s fault. Stanley was an intensely private person, humble about his comic book work and bitter about the industry that squeezed him out by the early 1970s, forcing him to take work as a silk-screener for a ruler factory. He only gave three interviews during his life, and two of them were at the sole comic book convention he attended. Thus, it’s no surprise to learn information on him was scant at best.

To his credit, Schelly does uncover a lot of valuable information, mostly about his parents and early years spent growing up in the Bronx. He also does a good job detailing the highs and lows of Stanley’s career, delving into the various personalities he worked with at Dell (including future Pogo creator Walt Kelly, listing the numerous titles he worked on, and even offering some genuine revelations, like the fact that he did some gag cartoon work for The New Yorker magazine. When the book reveals nuggets like that, or provides glimpses of never-before seen artwork or his layouts for stories, it earns its stripes.

But all the same it’s hard not to walk away from Giving Life to Little Lulu frustrated and wanting more. Stanley’s stories throb with so much life and vitality it’s a shame that his first biography fails to provide a more detailed and rounded portrait of the artist. Fans of John Stanley’s work will find plenty of reasons to like the book — not the least of which being the wealth of visual material provided. But those who are coming to his work for the first time should just sit down in a comfortable chair with a stackful of Little Lulu and Melvin Monster collections. Those comics say more about the artist than Schelly’s biography ever could. •

Feature image and last image created by Shannon Sands. Other images provided by Chris Mautner.