I’d waited months, nay years, for this moment. I was finally getting a tattoo and not just any tattoo but a tattoo of a Hamilton lyric after seeing the musical on broadway. In high school I was dead set on getting the Fall Out Boy lyric, “I can write it better than you ever felt it,” in dainty script across my rib cage. I was introduced to their music at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (or PAFA) summer camp in middle school and ever since, their music was the lifeblood of my of young angsty want-to-be-artist soul. So after seeing them live and getting into college as an English major, I felt I needed something to commemorate both my love for this band and for writing. But that was a childish notion (that my mother said absolutely not to). I was 17, what did I know about anything? Plus, now at 22, I barely even listen to Fall Out Boy. But Hamilton — a Tony award winning, constantly sold out, people of color driven narrative — was never going to go out of style.

Now after spending months scrolling through BuzzFeed articles about the best tattoo artists around Philadelphia and New York, I found the place, Bang Bang tattoo studio. The minimalist black and white building, the artist bios about how each person has carefully cultivated one skill or another, and of course the owner, Keith McCurdy, nicknamed Bang Bang for reasons I didn’t bother to google, who’s tattooed everyone from Rihanna to Adele. This was it. This was the place I was going to get my tattoo. After months of scrolling through images of script, watercolor, and portraits, the day was here. I should have been excited.

I took a sluggish L ride to 11th street and everything felt like it was moving in slow motion. People were half asleep slumped over their phones, lazily slurping coffee, and doing everything just to keep their bodies upright. You could have painted the scene without ever asking someone to stay still. The college dude in an oversized brown suit standing in the next doorway, one hand gripping the train poll, the other slowly losing its grip on a Dunkin Donuts coffee. The woman in her indigo scrubs with the worn Penn logo wrinkled and her head pressed against a graffiti engraved window. Her eyes glazed over poorly drawn “S”s and flashes of tile that proved we were indeed moving but focused nothing. I stood in the doorway close to the back of the train listening to the Hamilton cast album. Loud enough for a passer-by to hear the bass and give a disapproving look but not loud enough for them to hear the lyrics.

There’s a million things I haven’t done, but just you wait.

My mind wandered away from the music that was supposed to get me hyped up for this moment, that would bookend my doubts. I knew I wanted to be a writer but I didn’t feel like a writer. It seemed like the kind of thing that had to be boasted on you by some higher authority. Like Zora Neale Hurston needed to come to me in a dream and say “You are the next great writer,” or that I would see a piece of art and think “I have to do this for the rest of my life,” or that I would have to do something, like get a tattoo, to proclaim it to the world. I would tell my grandchildren “The day I got this tattoo was the day I became a writer.” Even though it should have been when I went to see Hamilton four days ago.

•

I was sitting five rows away from the stage, on the far right, with an obstructed view; a chunk of the stage was shrouded behind a pillar, but that didn’t matter because I was at the Richard Rodgers Theatre. After waiting almost a year to see Hamilton, I had less than ten minutes until the curtain opened and a miraculous thing would happen to me. My heart was beating so fast that I honestly thought it might stop before the curtain even opened. The chatty middle-aged white women who were mispronouncing all of the actor’s names didn’t matter.

“Did you know Hoveair was Hamilton?”

“No, but I had heard Lind left,”

The father that got last minute tickets on StubHub who had the audacity to be wearing jeans and asked me not to sing, at a musical, didn’t matter. Nothing mattered but me, my heartbeat, and this musical. I want to say I was there for the excitement of seeing a musical with this level of lyricism, craft, and symbolism. I wish that all I wanted was for the actors to be slowly spun like figurines in a music box as they performed on the turntables built into the stage to the songs I had obsessed over and memorized. But, that would be a lie. The year I found Hamilton, a writing professor told me that I would never make it as a writer because my had the nerve to assert my lived experience, as black woman at a predominantly white university, as fact and because my dyslexia made my editing process more expensive than others. So, this play became not just a story about people of color retelling the beginnings of America, or the complex life of Alexander Hamilton, but a story about becoming more than people assumed of you. Of writing your way out and not needing others’ permission or approval to be great. This was a story about me! So I sat there waiting for the next two hours and 45 minutes to affirm me, impatiently, as my heart raced.

My heart was the fastest thing moving on the train. It took everything in me to come back to the graffitied train doors and leave the curtains behind me. After getting off and climbing a flight of steps, I had to figure out the way to the Greyhound station. Even after living in Philly for 20 years, I still had no idea which way Filbert was because, I never had any reason to take the Greyhound. Plus, I was distracted by the watercolor sun and the fact that in a few short hours I was going to have something engraved on my body forever. I should have felt more sure. Once I found the bus station, the white fluorescent lights buzzing and the raspy half asleep voice of God saying, “Everyone traveling to New York City on the 201 bus, please line up in number order. Boarding will begin shortly,” I was reminded to save my existential dread until I was on the bus. The parade of commuters, couples holding hands and making nauseating remarks about how cute the other was early in the morning, children too young to know that complaining about how early it was didn’t make it any later in the day, parents double checking that they had all of their bags and children, and I, waited to get to the front of the line. The repetitive, almost rhythmic half steps everyone took once a person’s ticket was scanned were slow enough to rock a baby to sleep. Scan, step forward, scan, step forward, scan, step on the shoes of the person in front of you, apologize. I was finally next.

“Good morning,” I said trying to sound chipper for no apparent reason.

“Boarding the 201 to New York?”

“Yes.”

A scan, a thanks, and a weak, please keep it moving, smile later and I was on the bus sitting next to the person who was supposed to hold my hand if I started to panic. I was already starting to panic. Well, panic is not quite right, it was more that my anxiety was starting to bubble over, making every feeling more vivid and every thought more complicated. I noticed the hard plastic seats were cracked and whatever blend of polyester that once filled them was starting to fray and spill out. The seats were somehow both sticky, as if melted by the sun, and freezing against my back. It was December, how was it both? Once we were on the highway the driver made a game out of cutting off the every Prius in traffic even though there were no seat belts for his captive patrons. My fear slashed back and forth between getting in an accident and starting a discussion I couldn’t undo. My palms began to sweat as I clutched the side of the seat. This was how they could be both sticky and freezing. What if I was making a discussion I’d regret? My anxiety threw this question around my brain making it echo and overlap.

I’m not throwing away my shot.

I wouldn’t want to undo it. This meant a lot to me. It was a celebration of surviving my sophomore year. It was a reminder that I could get through anything. Hamilton survived a hurricane, crossed an ocean, and fought in a war proving that his words mattered. They mattered so much that someone took that time to write an 800 page book about him. I could sit still for an hour to get a tattoo from a hit Broadway musical! This had to be the decision. The thing that branded me as a writer.

But, I had made a series of decisions that told me it wasn’t. I didn’t major in Playwriting because I was afraid that it would limit my exposure to different kinds of literature, and because I was not sure if that was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. How could I know what the next decade of my life would look like at 18? The most important thing I had to pick between was if I should spend ten bucks on Ed Sheeran’s or Fall Out Boy’s album. But, not majoring in Playwriting meant that I had never had to edit a script. Which meant that I didn’t get the co-op at the Kimmel center because I didn’t have enough experience. So I shifted my focus and decided to get a co-op in editorial. But, I had just been told while holding back tears and sitting in another uncomfortable leather chair that I would never make it as a writer because no one would want to take the time to edit my work. But, I knew that I wanted to be a playwright. I knew that I could do it despite all of that and just needed something confirm it, to push me, to look at every time someone told me I couldn’t.

•

Hamilton was beautiful, whimsical, breathtaking, and the all the words you would use to describe an amazing piece of art in a New York Times review. I cried the moment the chorus said, “the orphanage.” There was something about the fact that after all that Eliza went through with Hamilton, she still opened an orphanage to commemorate him and their life together. I thought after listening to it all the way through 20 plus times that I would not cry. But, I was hanging all of my life’s ambitions on it being perfect. The thought that one moment would define how I would be was both overwhelming and underwhelming. But it didn’t. The cast gave their final bow, the dad next to me was a mess of tears. I would have roll my eyes at the fact that his face was the same color as the curtains if he was not so close. I bought a gray shirt that listed all of the founding fathers’ names in white and Aaron Burr’s name in red. One laundry day later, and that shirt would develop a hole near the neck (which was comical in hindsight).

I rushed past people to get to the Macy’s where my parents were waiting. Even though it was still light out and unnaturally warm for late December, my disappointment that Hamilton had not cemented my ambition to be a writer made it feel like it had dropped 20 degrees, making the green wrap dress I wore feel inadequate. The display window had artificial Christmas spirit, elves in their red and white uniforms slowly mimed packing Santa’s sleigh, their smiles with small paint chips around their thin lips, and crinkled plastic around their eyes giving them the appearance of having crow’s feet. It all seemed like a cruel joke. Once we finally got back to the car, it was dark, and I started to cry. All of the fears that I had been holding in for months came running down my face. I would never be able to create something like that, and I was not sure that I wanted to. Maybe the professor was right. Maybe I wasn’t a writer at all. At that moment I was filled with doubt about everything except that my dream of being a playwright was gone.

•

Why was I getting this tattoo? If that moment had not defined me, then what was the point of all of this? I needed something. The drivers’ reenactment of Mario Kart caused me to brace myself and push my glasses away from the edge of my nose. I needed something. That was it, all of it. I needed something. It was like being in middle school and really wanting glasses.

I wanted glasses so badly that I thought about failing the eye exam on purpose, but I was afraid that someone would find out through the magical all-knowing power of adulthood and I would get in trouble. It wasn’t that I was particularly interested in partial blindness, in needing to turn my head to see if something was coming on either side of me, or seeing hazy rom-com city lights once I took my glasses off, or the fog that impeded my vision when I went into a warm building after being outside in the rain or snow. I had no idea about any of those caveats to wearing glasses. I was 13, all I knew was that glasses would be a fun (mom-approved) way of jazzing up my all too regular face. When you’re a hormonal ball of insecurity sitting in the back of the class, you notice that everyone has a thing. Some people had really long hair, others had braces, some had the new Motorola Razr in hot pink, whereas I had the answers to last night’s math homework. But so did the teacher, so that wasn’t anything special.

I made the executive decision that I wanted glasses. Which meant failing the eye exam that I got every year. Those nine lines of poorly assorted black letters on white rubbery paper where all that was standing between me and my purple glasses. But the year that I finally did get glasses came with a bitter-sweetness to it. I stood there with my right hand covering my right eye looking forward at the size oriented letters. The America’s Best eye doctor sat legs spread, slumped forward with a clipboard in hand, avoiding eye contact. He looked like a cheap Halloween ghost with his whole body enveloped in his white lab coat and checkered vans poking out.

“Read the first line.”

Easy, “M.”

“Second line.”

Light work, “E F M A.”

“Switch eyes and read the second line again”

“Okay. E F N A,”

“Okay, switch back.”

Somehow between moving my hand over to the left side of my face, the M unbeknownst to me dropped a line an turned into an N. I had had dyslexia forever, but I was in second grade when I got the formal notice of it. Despite having a reading disability, I loved to read to myself, picture all the new and improbable lands that books like A Series Of Unfortunate Events and A Wrinkle in Time held. But, when it came to spelling tests or reading out loud, I would skip over words all together or replace them with something similar. P, b, and d gave me a lot of trouble despite my name, so at times I would go to write ‘beautiful’ and then just transition the first line to a p and write ‘pretty.’ I’m sure when reading this you noticed remnants of this, because, no matter how many times I edit, there is always something lingering. Anyway, my dyslexic brain would scramble letters, and glasses became my thing and my excuse when I was too embarrassed to explain why I said the word or skipped something entirely. I became the world’s lamest superhero and my glasses became my disguise.

•

I had no control over having dyslexia, or needing glasses, or what other people were thinking of me. This was something I had control over. I emerged from the greyhound unscathed and got onto the metro, which barrelled through Manhattan and into Brooklyn, in record time, and up the steps to a block that slapped me in the face with the odor of fish and fresh flowers. Somehow both rancid and familiar. Months of reading reviews and studying images so that I knew what to expect had prepared me for this, and yet no one said anything about the tattoo shop being right next to a Chinese market. Didn’t matter. It was a city. It was completely normal to have a fish market, a flower shop, a door decorated with a powder blue and faded pink ghost, and a famous tattoo shop within ten feet of each other. I moved down the block and into a small narrow building that looked like it could be the set of Smart House 2 with all of the white walls, flat screens playing a highlight reel that commemorated the shop’s celebrity clients, and the iPad you had to sign in on. All it needed was a hologram of a white woman covered in tattoos to represent the anthropomorphized store to welcome you into the tattoo shop of the future.

I went to check in and was asked to present my state ID, because apparently, I don’t pass for an 18-year-old despite being 20 at the time. I glanced over the waiver saying that I was indeed over 18 and not under the influence of drugs or alcohol, checked the boxes, quickly scribbled down my signature, and sat. I can do this. The tattoo artist I picked, Hector, walked over and asked me a few questions.

“Is this your first tattoo?”

Clearly.

“Where do you want it?”

My left forearm because I’m right-handed.

“You sure you’re over 18?”

For the third time yes.

“Ok, What are you getting?”

I’ll write my way out

“Oh, cool, a Nas lyric! I wouldn’t have pegged you for an old school rap fan.”

It’s actually a line from Hamilton, the Broadway musical.

After a short debate over the origin of my tattoo, Hector handed me an iPad and told me to scroll through hundreds of fonts and pick the one I like best. My anxiety raised the hairs on the back of my neck and I started to feel nauseous. I picked one after the first ten pages because the longer I scrolled through the endless abyss of slightly tweaked writing styles, the more nervous I got. Hector, shocked by my quick choice, took the font to the back and started to draw up a stencil. I watched a group of bros pick out a “tribal” tattoo to get on the bro leader’s bicep. I wondered how many google searches it took him to find that design and how many indigenous studies classes it would take to explain the actual meaning of that design and how problematic appropriating culture was to the gaggle of bros. Meanwhile, a woman behind a semi-transparent black curtain was getting her sternum tattooed and lying perfectly still, only getting up once to make sure her breasts weren’t covering any of the design.

I was doing this.

An hour later, the artist got back with a design three times bigger than I imagined or requested. After being told that because of my dark skin a two-inch tattoo was not an option, I rolled with it. He would know best, right? Stencil on, panic rising, I looked at my arm now consumed by a six-inch quote. I’ll write my way out sprawled over more than half of my forearm.

Was I doing this?

“Can I have a minute to think about it? It’s a lot bigger than I thought.”

“Sure take your time, I’ll be in the back.”

How many people did an anxiety-ridden introvert have to call to make a decision? Trick question, the limit doesn’t exist, but I called two and asked the person I came with. Was this too big? I looked at myself in the full-length mirror over and over again. Pacing around the slowly encroaching building. This was just like Smart House because I was trapped by a thing that wasn’t even a real person! Why couldn’t I leave?

- Because I already put down a $100 deposit.

- Because I told people about it.

- Because I had been saving and doing research for months.

- Because I just dragged someone with me on the world’s most uncomfortable bus.

- Because I hated inconveniencing people and this would be the most inconvenient thing ever.

I didn’t like stepping on the backs of people’s shoes or correcting professors when they mispronounced my phonetically spelled name. How could I say that the tattoo I wanted was too big? I needed this, I needed this, I needed help!

In the eye of a hurricane, there is quiet. For just a moment, a yellow sky.

•

We were on a roller-skating trip for making the honor roll. It was basically a trip for the nerdiest kids in the class. The one moment when knowing the answers to the math homework mattered. We rode in a yellow school bus 30 minutes outside of Philly. The building looked like it had been there long before everything else around it. It had clearly been painted over several times as the newer white paint was starting to peel exposing past layers of discolored almost yellow paint underneath. The parking lot around it was an even dark gray with fresh white paint showing off its newness with its lack of gum and stains. We were not the only school incentivizing good grades on that day because two other yellow buses were lined up in front of the entrance. Once we entered the building, we could see that it was split into two levels. The top floor had skee ball, pinball, and pretty much every other old school arcade game. There was a prize counter filled with beanie babies and Powerpuff Girls paraphernalia. The bottom floor had a food stand and the skating rink.

“Let’s go get skates!” said my thin, lanky, and perfectly balanced best friend Katherine.

“Okay,” said me, the 11ish, short, chubby, clumsy sidekick.

I was not going to say that I didn’t know how to skate, so I went over the wall that had roller skates in an assortment of colors and sizes that were stacked behind the looming, maybe 16-year-old with acne. This would have been a totally normal interaction for anyone else, but to me, it was like walking into a forest during the blood moon and bumping into a witch with a cape full of vials and potions that were all filled with some kind of child-killing magic. But, I survived the witch, asking for a pair of size eight pink skates and after spending too long double knotting them, my best friend was gone, lost in the forest of teenagers, vintage games, and teachers from different schools. I was alone and I could not find the ramp that I knew had to be somewhere. But every face seemed less interested in my worry then the last and I didn’t want to bother anyone with, well, me. So while holding onto the wall that separated the first and second level, I stumbled my way over the three stairs that separated me from everyone else who was having fun. I had just confronted a witch and lived, I could do this! I could get down three stairs. So I took a step, slipped, and tried to brace myself with my right hand. Then a world of pain shot up my hand.

There are moments that the words don’t reach.

•

Looking down at the not yet permanent life choice on the arm, I knew I couldn’t do this. Not like this anyway. My anxiety ebbed, the walls were back in the rightful place with their real importance. They were not a labyrinth, or roller rink, or the room where I got my eye exams, or a theatre. They weren’t a crystal ball holding magic and my future inside. Hector was not someone I owed a blood debt to. They were just the white walls of a tattoo shop in New York, and I was just a person trying to find myself in places, and musicals, and glasses, and tattoos. “I’m sorry but this is just a lot bigger than I thought it was going to be. So I’m going to go and you can keep the deposit.”

Let me tell you what I wish I knew when I was young and dreamed of glory.

In that moment I felt perpetual numbness, like I let my anxiety win. When in reality, it was the best decision I could have made. You should never get a tattoo to prove someone else wrong or to confirm something about yourself. It had nothing to do with the tattoo. It had to do with proving myself and having something that would define me as a writer, but, being able to point to a tattoo and say, “Look, I’m worthy of this title because I branded myself with it,” doesn’t make me a writer. The encouragement and approval of everyone who reads my work doesn’t make me a writer. Seeing an award winning play on broadway and saying “I want to do that” doesn’t make me a writer. There is not magic to this. No shortcut or easy way. The reality is that to be a writer you have to write. Even when all of the things you thought were going to confirm your passion fall apart, you write. Even at its best, writing is work. Hamilton was seven years of work, and in all of that time, Lin-Manuel Miranda was still a writer, even if less people knew. I am a writer, even if I am the only one who knows. •

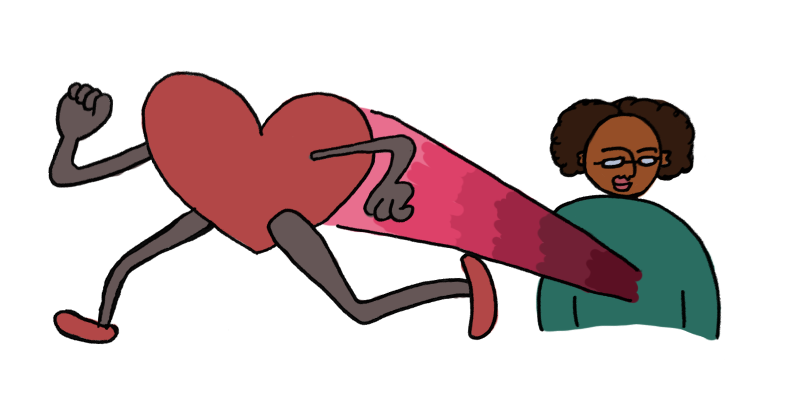

All illustrations by Isabella Akhtarshenas.