The Smart Set: To help English majors with term papers forevermore, what does “The Skunk” mean?

Kay Redfield Jamison: “The Skunk” in “Skunk Hour?” [laughter]

TSS: Yes, exactly. You quote what Lowell has to say it means, but I was curious: After all your time with the poem, do you have a sense of “The Skunk”?

KRJ: I don’t, really. I think it’s part of putting a defiant, fascinating, interesting – as it were, black and white – character in the midst of a dark night. It has the quality of being whimsical, but I think the imagery that he gives to it is one of a great deal of courage.

TSS: About halfway through the book, you focus on the issue that’s been sort of dancing around the edges: Is there a connection between Lowell’s mental illness and his creativity? What made Lowell the poet you wanted to study for this? Was it getting his medical records that was the catalyst?

KRJ: No. When I started writing the book and thinking about the book and writing the proposal, I didn’t have any thought of getting his medical records. He’s a poet I have loved and admired since I was 17 or so. I find him a fascinating poet, a wonderful poet. And I also find him a fascinating human being who had to contend with a great deal of suffering and did, I think, in a remarkably courageous way. Mainly, I love his poems.

TSS: Did you have a chance to know him?

KRJ: No, I didn’t. I was living in California, and I was doing science and psychology so . . .

Read It

Setting the River on Fire by Kay Redfield Jamison

TSS: What made you decide that the key to understanding Lowell’s poetry was his personal ailments?

KRJ: Well, I don’t think that is the key. I think it’s a key. I mean, I think if nothing else, what stands out with Lowell is this hugely complicated, elaborate, brilliant, metaphorical, three-dimensional mind. So I don’t think that any one thing explains anything. I don’t think you give mental illness to somebody who’s not brilliant and have him come up with that kind of poetry. I think it’s one aspect of it. And it’s an aspect he wrote about a very great deal. He wrote about it in his letters. He wrote about it in his poetry. He wrote about it in his prose and he talked about it a lot with his doctors. So it’s not that there wasn’t a relationship: I just don’t think any one thing begins to explain someone as complicated at Robert Lowell.

TSS: You have a lot of praise for later poetry like Day By Day that most poetry critics have dismissed. I was curious; do you think it’s time to re-look at that poetry? What is it in there that people have missed?

KRJ: Actually, it’s interesting. I do think people tend to dismiss it, but a lot of people think it’s some of his best writing. Helen Vendler, for example, and Frank Bidart. There are several people, poets and poetry critics, who believe that it’s the most human and compassionate and, in many ways, beautiful poetry that he wrote. I hope it’s reconsidered because it’s an extraordinary piece of writing. I think what stands out about Lowell is how many different types of poetry he wrote and how many different phases he went through. That is one of those things that is quite striking about him. He didn’t linger on. He kept on moving. He kept on creating something new.

TSS: And yet he was always willing to revise the old –

KRJ: For sure! For sure.

TSS: Nothing was ever finished!

KRJ: Yes. When you go to the library [to look at manuscripts], he has a combination of incredibly bad handwriting and, when you look at a poem, he has 30 pages on the poem of revision. So it’s a nightmare if you’re actually trying to – what you can see is that he revised a lot.

TSS: And not always for the better. Of course, that’s a subjective opinion. He wasn’t someone who had trouble creating new work, so why was he always revising the old?

KRJ: I think he was absolutely fastidious. Jonathan Raban said he wrote when he was manic, and he revised when he was depressed. There was definitely some truth in that. He went over things to try to make them better. I think he was a perfectionist in everything he did.

TSS: So it wasn’t a case, as with Auden, where he was revising the poems to make them in line with changed convictions?

KRJ: I don’t think so, no. I think he genuinely would have a new idea about a word or an image or that he could improve something that he wrote. If you look at his original spewing for a poem, the final product is so far removed from that. You can just see that he just took it and went after it over and over and over again.

TSS: Could you talk a little bit about, at the end, what Caroline Blackwood and Elizabeth Hardwick represented to Lowell?

KRJ: They represented quite a few things. They both were really good writers, and that was hugely important to Lowell. He once said that he never got credit for marrying really smart writers. He admired both of their work a lot.

He was deeply in love with Caroline Blackwood, so I think she was really a passionate love and love affair in his life. And it just turned out unbelievably tumultuous.

With Elizabeth Hardwick, they had been friends for a very long time and they were close. I think she represented, as he said over and over again, a certain peace and quiet towards the end of his life. Towards the end of his life, things were so fraught and painful for him that he went back to some of what he knew.

TSS: Including her?

KRJ: Including her. Yes, he went back to her.

TSS: Did you read all of the sonnets?

KRJ: I did, actually. I’d be hard-pressed to keep them straight. I actually like the sonnets. It’s one of those things that are perhaps an acquired taste. Some people think it unformed and indulgent, and they just go on and on and on. And they certainly go on. I find it fascinating just kind of watching a mind in progress and that kind of just freeform – well it’s not really freeform, it’s a sonnet, but free for thinking.

TSS: Again, frequently revised.

KRJ: Frequently revised, and very much revised for the second version. Then, of course, he put them in yet another form. There was an initial book of sonnets, then another revised book of sonnets, and they went into three different books from there.

TSS: Is this Lowell’s illness or just his aesthetic vision? Was it something he was trying to find in those sonnets? I mean, he’s capable of an incredible range of other forms.

KRJ: One of the suggestions has been that he [was] put on lithium at the time he really started writing the sonnets, and that perhaps he was still pretty driven but more controlled. So he kept on writing, kept on writing, but there is a very driven quality to those sonnets. I mean, obviously, they do keep coming out.

What happened with Dolphin is that he really began to put it into a story form. Likewise, there were many themes. Then the Lizzy and Harriett theme and a few love affairs he took out and put together. The story of his relationship with Caroline Blackwood, their marriage, their child, and then the dissolution of their marriage.

TSS: A question for a biographer, I guess, and for a poet: How comfortable were you with the material he used in his poems?

KRJ: Well, it’s obviously hugely controversial. I think that he did what he felt he had to do. Elizabeth Bishop had said, “Art isn’t worth that much.” Lowell’s view was it was worth that much. I don’t know how much of a moral component you come down on in the use of things in poetry. Because in many respects poets have been doing that for hundreds of years. Using personal fragments, conversations, betrayals, love affairs, and things said in the middle of the night or in anger and rage. For Elizabeth Hardwick, it was very painful for her. I think that her daughter, their daughter, made that very clear. No matter what, I think that Elizabeth Hardwick forgave all. But she didn’t forget it. It’s very hard.

TSS: A flip response, being “That’s what you get for being involved with a poet. They go off and write poems about it.”

KRJ: In a way. I don’t know. If you start getting too much into any field, whether you’re talking about scientists or talking about poets or humanists or historians or politicians or anybody, at some point you’re evaluating them on what they did with their work. What they achieved. What they left behind. Whether they left the poetic world a better place. And the other is: What was the morality in which they lived their life? And Lowell had complicated morality. He hurt people a lot when he was manic, which people do, and he tried to make those things right. I don’t think he could always make them right.

TSS: In your appendix, you talk about the medical records you used but you also talked about the medical records you didn’t use.

KRJ: Right.

TSS: I’ve never heard of a biographer not grabbing every piece of paper in sight, so I was curious why you decided not to use them, and, second, how you drew the line between what to use and what not to use.

KRJ: When I started to write this book, I was interested in what was Lowell’s view of his illness. How does his illness affect his work? And what was the nature of his illness? I mean my specialty is mood disorders, and I was interested very much in what were the patterns of his moods. How did they unfold over time and treatment and so forth?

I felt that going into the psychotherapy notes, I know I had every legal right to do that, I felt like I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to talk about an illness and his attitude towards his illness. What I was very interested in, which came out in his discussions with his doctors, was how frightened and terrified he was that the illness would come back. And his attitudes about mania, what he thought about mania and what he thought about mania in his work. I wanted to draw a line. I know a lot of biographers would not have done that. I’m not a biographer. I wrote a biography, but that’s not my line of work. I just felt like I wanted to keep that private, and I discussed this a great deal with Robert Lowell’s daughter –

TSS: Are there still sensitivities this long after his death?

KRJ: I don’t know if there is any sensitivity; there is privacy. No, I don’t think there is any great sensitivity. Robert Lowell was about as open as you can be, as was Elizabeth Hardwick. One of the things very clear to me, that made it more straightforward to write about what I did, is that they had made very conscious decisions throughout their lives to deposit some of this information in the public record at University of Texas and at Harvard. One of the things that is interesting about Robert Lowell was that in a day and age when men didn’t talk about their feelings very much and, people in general, didn’t talk about mental illness very much, he did do that.

TSS: This is sort of an odd question, but I’ve interviewed a few authors of biographies before who are less impressed by their subject when they finish than when they started. You seem to be as besotted by Lowell as someone could be. Has writing this increased your joy in his work?

KRJ: I wouldn’t say besotted; I would say impressed, deeply impressed. It’s funny you say that, because there are a quite a few of my friends who do write biographies, and they talked about how you get jaded and you see all the tawdry sides and so forth and how badly they treated other people.

First of all, Lowell was out there to some extent anyway. And secondly, I ended up just deeply impressed with his personal courage, as well as his work. People don’t write about courage very much, but if you know this illness and how difficult it is and what a bad form of it he had – How many people ended up loving him all of his life, maintaining his friendships from school days to his death. Many of his pallbearers were people he knew in school. He kept his relationships even though he was difficult. I think people understood that he had an illness that was really beyond his control, and he certainly alienated people along the way. It’s also true that in a way what I hadn’t been so aware of is how much he used exemplars and heroes and consciously studied them. He did everything he could do to contend with a kind of suffering that most people don’t have a clue about. So I don’t think “besotted” is a good word, but “admirer” – absolutely.

TSS: He also had peers who were famously troubled, perhaps in different ways, like Delmore Schwartz, John Berryman. Is there a risk we have of glamorizing the drinking and the illness that somehow that this is what you need to do to be a poet?

KRJ: I hope that doesn’t come across in my book, because I tried to say about 500 times that it’s just not true. There’s nothing romantic about these illnesses. I’ve got so many family, patients — there’s nothing in the least bit romantic about it. That there’s a relationship that has been pretty well established among that group of poets who were particularly struck by bipolar illness, by mania, and by depression is how much they reached out to one another. One of them would be going in the hospital, manic, and the other one would be commiserating, offering friendship, offering a hand and so forth. And I think that that is a sort of interesting aspect of both friendship and collegiality amongst that group of poets.

TSS: Now part of what Lowell suffered from was illness, but part of what he suffered from, particularly earlier in his career, was treatments of the illness.

KRJ: His diagnosis was pretty well understood. It’s been around for thousands of years, and he was, with one or two unusual exceptions, diagnosed with the same thing over and over again. So people understood that he had mania. What was not so clear, in that day and age, was what to do about it. The only options you had were to put somebody in the hospital, and, in his early illness, they gave electroshock treatment. Then, later on, over the years as medicine does, it progresses, and there were more treatments by the end of his life. Lowell was put on lithium.

TSS: And that worked better for him?

KRJ: It worked, yes. He was very enthusiastic about lithium because it kept him out of the hospital for the first time in years and years and years and years. I think it was problematic in its way, but he felt very indebted to it.

TSS: Lowell’s never really comfortable being called a confessional poet. What do you think of that label regarding his work?

KRJ: Most people who study and certainly the people who knew him, the poets who knew him, didn’t like the label. It’s a rather dismissive label: sort of sounds like something out of True Confessions Magazine. It sounds like a much less disciplined and much less universal form of art: a kind of memoir-ish diary type thing. When in fact what he did was write his experience into a much more universal experience, and he did it incredibly well. So he very much disliked it. He didn’t like being lobbed in with – and Elizabeth Bishop didn’t like it for him either. She was always trying to make the distinction: Anne Sexton is a confessional poet over there, but you’re anything but. Your work is different.

TSS: At the time of their deaths, Lowell would have been more famous than Bishop. But that has changed significantly. Why do you think that is that people have not continued to appreciate Lowell as they did during his life?

KRJ: Well, I’m hoping people are changing a bit. Partly she has a much more comprehensively sized body of work than Lowell. I mean, if you look at their collected works, one you have to put in the wheelbarrow and the other you have a manageable size. Her work is more comprehensible in general. I think he painted a much wider canvas than she did. The fact that he so dominated the field – anybody who dominates a field that much risks blazing out in a way. There were a lot of poets who just didn’t like being under his influence so much. He was so dominant in a series of styles and so dominant a force that people felt almost embarrassed that they had been beholden to him. Almost embarrassed that they’d turned over so much of the poetic geography to him. I think a lot of the people I interviewed who were poets felt very similarly. My guess is that people have more interest in Lowell now than they did.

TSS: The degree to which he dominated this era is sort of hard to understand now, but it was also a period of incredibly talented peers and colleagues from Randall Jarrell, Berryman, and Schwartz – I could go on and on – he didn’t just win a couple more awards than them, he was considered by all of them the dominant poet of the period.

KRJ: Exactly. He had sort of a gale force about him and his work, and he had an originality. I talked with many poets who’d been influenced by him. They could all remember where they were when they read “Waking in the Blue” or “Mr. Edwards and the Spider” or, particularly, “Quaker Graveyard”. They could remember it because it just was a bolt: an original bolt. He really was an original maker. As Frank Bidart would say, an audacious maker.

TSS: When Lowell died, he wasn’t so old as just worn-out by life.

KRJ: Absolutely. That’s a good way to put it: absolutely exhausted. Been through everything, and I think he was ready to die. My husband’s a cardiologist and he went through all his medical records and he was saying, “You know, you have a sense like you do with some patients who’ve had a chronic illness that they just are ready to pack it in. They’ve just been through too much in a way.” Lowell didn’t give up; he had just been through an incredible amount. He would be the first to say he had an enormous amount of joy. It’s that capacity to entertain the contrary belief that to me is very attractive about Lowell. There is not one way of looking at things. He would certainly, and did, focus on suffering, but he also focused on joy. •

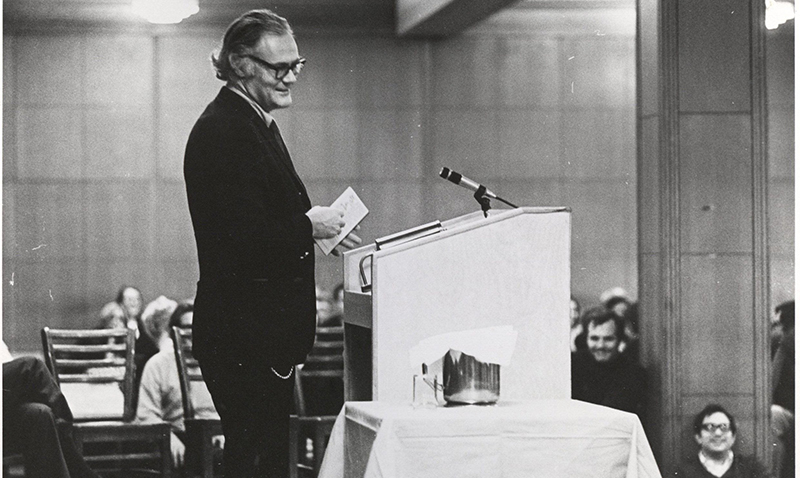

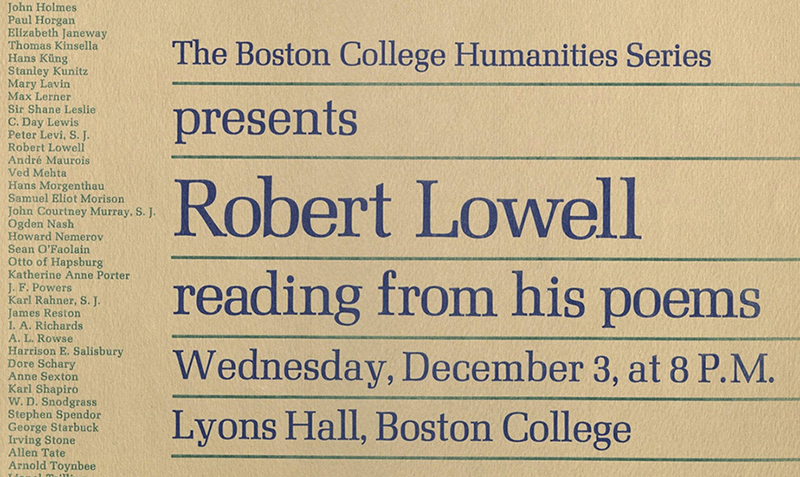

Images courtesy of Elsa Dorfman and cmacauley via Wikimedia Commons and Burns Library at Boston College, jakubkadlec, and Windslash via Flickr (Creative Commons).